LISTEN: Craig Finn & The Band Of Forgiveness Has The Mountain Stage Song Of The Week

On this week's premiere broadcast of Mountain Stage, guest host David Mayfield ...

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

This story originally aired in the Nov. 17, 2024 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Morel mushrooms are popular in Appalachia, where people here have been eating them for generations. Morels are not always easy to find, though.

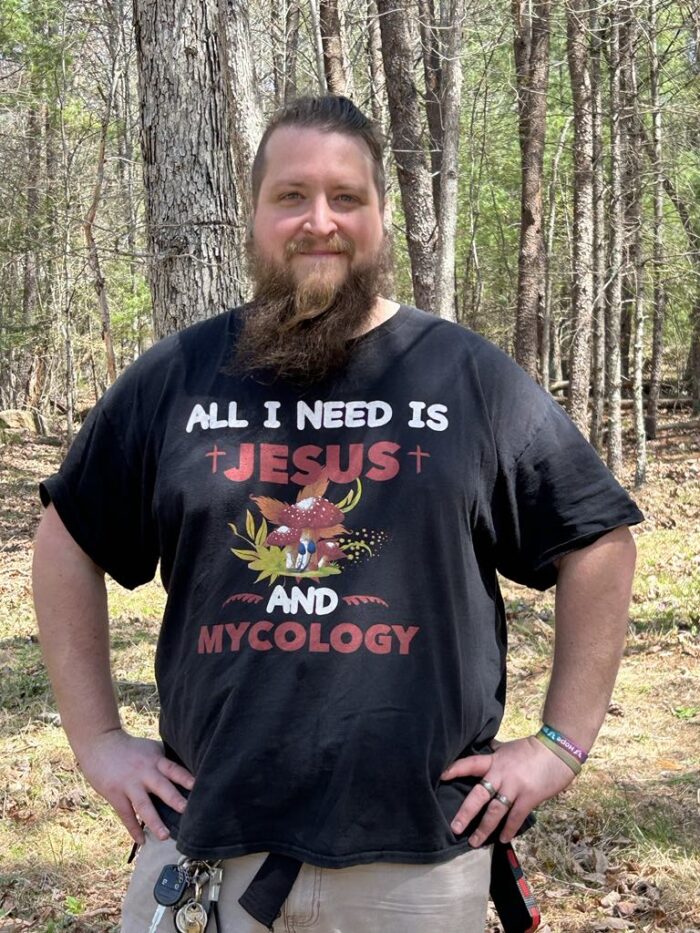

“Yeah, they’re definitely one of the more difficult mushrooms, I think, to find,” says Virginia Master Naturalist Adam Boring.

Boring grew up in the town of Appalachia in southwest Virginia. He became a recognized expert by learning from experienced hunters. After his first mushroom hike in 2018, he began reading all the information he could find about fungi in central Appalachia.

“I joined the Virginia Master Naturalists, and at the end of my training class, there was nobody who taught a mycology course,” Boring says. “And one of the other Master Naturalists, he said, ‘Hey, Adam, you seem to like mushrooms, you should teach a class for us.’ I just kind of dove headfirst and didn’t look back.”

To find the elusive morels, Boring recommends looking for a poplar or sycamore tree, and then nudging leaves with one’s toes until something that looks like a tiny tree or a beehive appears. Morels tend to be small, so it’s easy to miss them in the leaf litter, Boring says.

“Sycamore leaves are very big and bulky and create a deep layer of leaves, and they can hide underneath those leaves. You can walk over them and never even know that you’ve found them until you accidentally kick over the leaves and expose them.”

If one is lucky enough to see a mushroom emerge from the leaf litter, check carefully to see if the mushroom is more rounded than pointy, resembling an ear or a brain. Those are likely false morels.

It’s common for first-timers to head home empty-handed, says Elissa Powers.

Powers was raised in Pound, Virginia, in a coal community called Bold Camp. Her father is a renowned morel hunter. He taught his three daughters all the tricks of the craft.

“We would just pack up on a Saturday morning if the weather conditions had been right for it in the month of April,” she says. “And we would just pack up the whole family and go, and I remember being taught that when you see the first one, you’ll know where to find the rest. And it’s hard to explain. But it’s very true,” she says.

Powers found her first morel at about age eight and has been finding them ever since, in season, and usually in company with other family members. She has fond memories of these annual hunts while growing up.

“It was a treat. It was special. It was seasonal. I’m 47 years old. We’ve done this all our lives. My entire family does it. Both sides of the family.”

Powers’ father taught her to bring home the morels, but it was her mother who taught her how to fry them up in a pan. In her home kitchen, Powers demonstrates how to run a sink full of water, add salt, and submerge the mushrooms. Leave them to soak for at least an hour, she says.

“I have never had them cleaned any other way besides the saltwater soak, and I’m probably not very interested in any other way, either, after I’ve seen the water – the things that come out of them.”

Those “things” include spiders, mites and centipedes, so don’t skimp on the soak. Next, slice the morels in half. This is both a final safety measure and what gives them their nickname of “dry land fish.” Sliced lengthwise, a true morel should resemble a gutted fish. Its stem will be hollow.

“If it’s not hollow, you do not have a real morel,” Powers says. “Cut them in half lengthwise, and that way you can get anything that has crawled up in there out. You do not want to be visiting a whole morel that is hosting a family of centipedes. You will never forget that, and you’ll never forget to split them open and clean them again.”

The Powers family has been known to consume more than 30 dry land fish in one sitting, so leftover morel storage was rarely an issue. But morels do freeze well if you cook them first, Powers says.

“You can keep them, but since they’re a mushroom you can’t just pop them into the freezer. Because once the little ice crystals form they’re gonna destroy the cells and you’re gonna be pulling mush out of the freezer later. But if you prepare them, clean them and cook them oily as you are going to consume them, and then put them in the freezer, they will be good.”

Indefinitely, Powers adds. Her family often pulls them out for Thanksgiving celebrations six months after freezing – if they can keep them that long without digging into them.

“I am not sure how many morels I’ve eaten in my lifetime. But I’m sure it’s more than most people have ever seen. I would say now, in my adult years, where my dad – my morel concierge – brings them to me, I’ve probably got a couple of dozen a year at most,” Powers says.

Over in Abingdon, Virginia, Ben Carroll would like to see more people eating morels. He is the owner and executive chef at Rain Restaurant, open only for evening meals and renowned for upscale dining.

Carroll triages how he cooks morels according to size.

“If they’re little bitty guys that are as big as the tip of your thumb, then you just keep them whole. And then you would just batter and fry them like you would any kind of battered mushroom,” Caroll says.

The big ones, he uses to explore culinary creativity.

“You can stuff them. We’ve made mousse before – used a little piping bag to fill them with some type of filling, and then you bread them and fry them. They’re good that way, either like a cheese filling or a pâté kind of filling.”

He does not suggest serving morels raw, though. Caroll considers it a safety issue – and a matter of taste: morels are better cooked.

Just remember, safety first: go with an experienced morel hunter, and never eat any mushroom not properly identified and prepared.

——

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia.

The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts and culture.