This conversation originally aired in the Nov. 9, 2025 episode of Inside Appalachia.

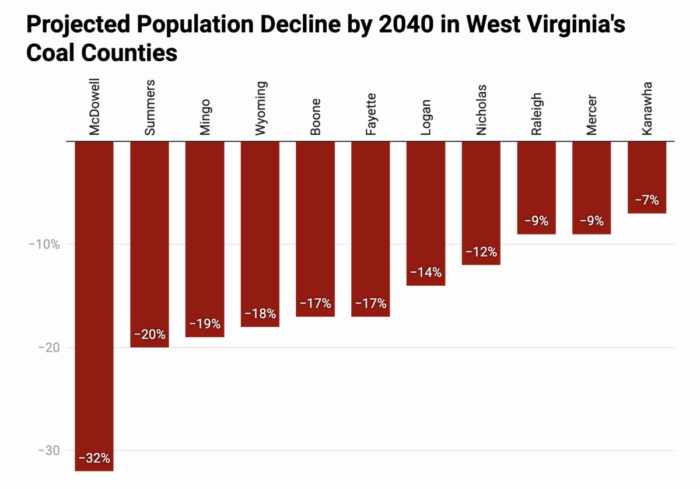

A series of population projections paint a dire future for coal-producing counties in central Appalachia.

The region’s current and former coal-producing counties have had a rough time since the post-World War II boom in the 1950s. As the coal industry has mechanized and shrunk, those regions have seen a loss of jobs and young people.

These new population projections show things might get even worse. Jim Branscome is a longtime journalist who grew up in southwestern Virginia and spent time working at the Appalachian Regional Commission.

Inside Appalachia Host Mason Adams spoke with Branscome.

The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Adams: The headline of your recent story in The Daily Yonder is “The Alarming Depopulation Of Appalachia’s Coalfields, A Quarter Century Of Projected Decline.” I’d like to read the first couple of paragraphs here, because they’re pretty stark.

“By 2050, entire counties across Appalachia face the loss of nearly half their populations in what demographers describe as an accelerating demographic collapse unprecedented in American peacetime history.

“The demographic projections paint a devastating picture for the Appalachian coalfields. According to data from three major state universities, central Appalachia faces population losses that rival the depopulation seen in war-torn regions or economic catastrophes abroad.”

So, what is happening in the region?

Branscome: It’s quite alarming. Mason, I first spotted the problem from reading Cardinal News. Dwayne Yancey had an article about the projections that were coming from the Weldon Cooper Center at the University of Virginia, and I wondered if anybody had taken a look at what was happening across central Appalachia as a whole, and I didn’t find anything. So, what I did was pull up the numbers from University of West Virginia and University of Kentucky and do a profile of what was going on in what we usually call [the] main coalfield regions. That’s central Appalachia: 60 counties in eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia, East Tennessee and southwest Virginia.

The numbers are just startling, to say the least. The projections are that Buchanan County, Virginia’s population over the next 25 years will decline 48%. Harlan County, Kentucky, the projections are able to decline 45%. In Breathitt County, Kentucky, where J.D. Vance traces his roots to, it’s 39%. Across southern West Virginia, it’s similar numbers. McDowell County, West Virginia, has sort of become the poster child for depopulation, going from about 100,000 at its peak down to about 18,000 at its present time.

So, we’re looking at something that’s never happened in peacetime America. And of course, those familiar with the history of Appalachia know that between the ‘50s and the ‘70s, we had about three million people leave the Appalachian region, migrating to the cities in Ohio. But there’s a significant difference between what was happening then and what’s happening now. What’s happening now is that there’s not a young population left to repopulate the region. In the ‘70s, we still had a young population that could repopulate the region, and that happened across the region as a whole. In 1965, when the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) started out, the population in the region was about 22.5 million [people]. Today, it’s 26.6 million. The southern Appalachian region in particular has been growing, and the dynamic is that we’re in a spiral here. The basic premise of what the demographers look at is that we are basically exporting the future population of Appalachia to other regions of the country.

Adams: Some of these numbers for Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia are just eye-popping, and they’re all in current or former coal-producing communities. Why are these areas seeing such stark projections?

Branscome: It’s the collapse in the coal industry as a whole. We’ve gone from 100,000 coal miners at the end of World War II down to just a few thousand now across the region as a whole. Unfortunately, all of the promises that the politicians have made that they were going to do something about the situation just haven’t happened. We’ve just allowed these communities to continue to deteriorate, the population to leave the tax base, to decline, people to migrate to find work or commute extremely long distances to work.

When you get down to some of these population levels, you have school consolidations, you have birthing centers closing. You have hospitals closing entirely. You have fire departments that can’t maintain a volunteer fire department. Just the whole basis of what we all call “vibrant communities” begins to collapse. You end up with an aging population. The population age of the central Appalachian counties is now approaching 50 [years old], actually. At one point, Buchanan County, Virginia, had a younger population than the average in the state of Virginia. Now it’s much older.

Adams: If you look at social media, it sometimes feels like the sign of the times is the laughing emoji response. Some people are definitely going to hear this and go, “So what?” Why does this matter for those communities, but also for the rest of us in greater Appalachia?

Branscome: It matters a lot for Appalachia. I think it matters a lot for the nation. Let’s just start out from the cultural aspect. If it hadn’t been for the Appalachian Mountains, we probably wouldn’t have country music and bluegrass music like we do today, but more importantly, maybe you wouldn’t have some of the important things to the future. I spent a lot of time studying what’s going on in the drought in the West. We have an unprecedented drought that’s been going on for 20 years from Colorado west to California. We grow over 50% of our vegetables in California, in Arizona, and transport it across the country. That cannot continue. We’re not going to have the water to continue doing that. Where are we going to grow the food? Well, the best place to grow the food is going to be back in Appalachia. We can replant a lot of these broom sage fields, and we’re already seeing signs of how it can be done. We’ve got a number of what I would call vertical agricultural innovative projects in Appalachia. The most famous, probably was the AppHarvest, which unfortunately went bankrupt, but the AppHarvest greenhouses in east Kentucky are still being utilized by other corporations.

There’s a dramatic new company in Carroll County, Virginia, my home county. Oasthouse Ventures is a United Kingdom company starting a $100 million innovative agriculture experiment to grow tomatoes. And the reason is simply because the water is there, the people are there, the workforce is there, the transportation is there. We’ve got a lot of land on which you grow food in the region. The second reason is, I think Appalachia can be an experimental area for how you deal with climate change overall. Unlike Elon Musk, I think “Planet B” could very well be Appalachia. I think we can get to Appalachia before we get to Mars.

Adams: There is one group of localities in your article that fit the profile of many of these others, but they’re seeing different outcomes. And that’s the counties in Tennessee. What’s happening there that’s different from the rest of this region?

Branscome: The population is actually reversing and growing in these Tennessee counties that have been historical coal counties. Tennessee ceased to be a coal mining state in 2021 for the first time since the 1890s, and currently there’s only one permitted mine in the whole state. What’s happening there is the Tennessee Valley Authority has been pulling back on coal-fired steam plant generation. That’s one factor.

The reason the population is starting to grow is easily explained by anybody who drives up Interstate 75 from Knoxville towards Lexington, Kentucky. It’s just beautiful, beautiful country. Knoxville has become a bit of a growth center. It’s on two major interstate highways. It’s had some intelligent planning, and the same applies to Oak Ridge just north of there. So, it’s an easy commute from the Oak Ridge areas and Knoxville areas up into the historical coalfield counties of East Tennessee. Plus, there’s been some very decent looking ahead by leadership in those counties. And so, the net result is some lessons that probably the rest of the region could take a look at.