It could be argued that West Virginia has never been “owned” by her inhabitants. Before European settlement, of course, ideas of land ownership were not in vogue. Then King Charles II rewarded many loyal friends with large swaths of land and by 1730s, 800,000 acres in what would become West Virginia was owned by three land companies. For the most part, the same trend continues three hundred years later.

Some have argued absentee land ownership in West Virginia has been a major impediment to economic diversification for generations.

But who exactly owns what today, and to what extent? That’s the question Ted Boettner, executive director of the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, decided to pursue.

“What we tried to see is, ‘How has this changed over the last couple of decades?’ and ‘What’s different?’ and ‘How can we learn from it?’” says Bottner.

“It’s hard to think about economic diversity if we don’t know who owns a big portion of the private land in the state. It’s very difficult to move forward, especially in the southern coalfields which see very high concentrations of land ownership, if we can’t have a say in what the development is going to be because we don’t own the land,” Boettner explains.

“Who Owns West Virginia?” is the name of the report from the nonprofit think tank. It’s the first major investigation into land ownership since a couple reports in the 1970s definitively tackled the issue, identifying the major absentee corporations that held titles to huge land swaths—especially in southern West Virginia.

What’s Different?

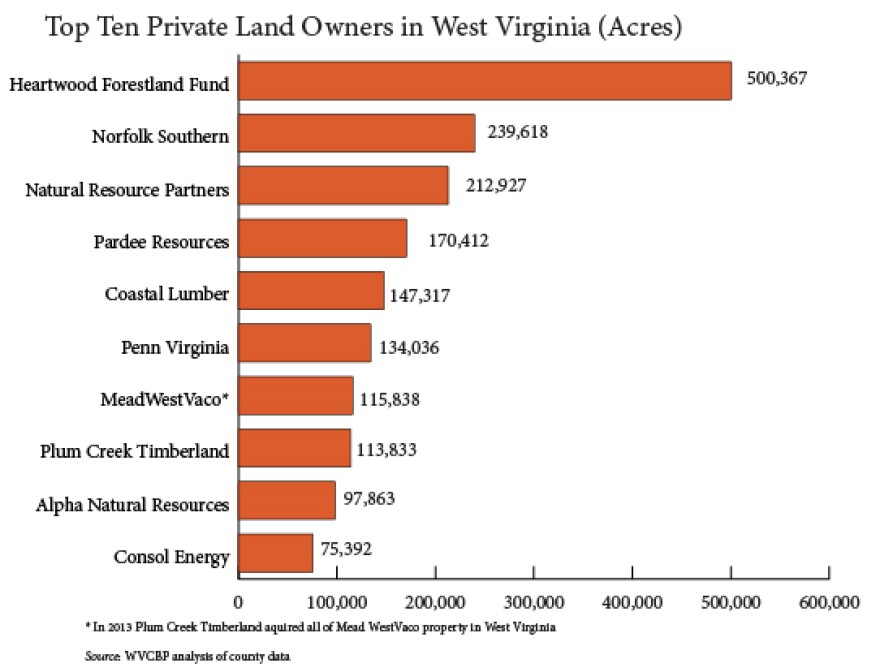

“Over the last several decades land ownership has transitioned from energy companies like Consolidated Coal Company, to timber management companies whose major business interest is to manage money for investors,” Boettner says.

The report found that West Virginia’s largest landowner is North Carolina-based Heartwood Forest Land Fund, owning more than a half a million acres across 31 counties. There are several of these Timberland Investment Management Organizations (TIMOs) in the top 10 land owners in the state.

Boettner explains that TIMOs are a relatively new corporate invention forged when economic factors converged with changes in the natural resources business sectors in the 1980s. TIMOs manage industrial timber investments and/or institutional investment clients such as pension funds or endowments of foundations and universities. He says there’s been a major shift away from vertical integration business models toward these financial holding companies.

Boettner points to Consolidated Coal as an example of previous business models. In years gone by, the company owned land, mineral rights, coal mines, and produced a product. But he says times have changed.

Boettner’s report also highlights the regional differences in concentrated land ownership—some of which have changed over the last 30 years. But there are still large areas of concentrated absentee land ownership in the southern counties where the highest poverty levels in the state happen to exist, along with all the health disparities and daunting economic challenges that come with them.

What Can We Learn?

Boettner says his report only scratches the surface of the issue, literally and figuratively. He says mineral ownership still needs to be investigated as well as how many companies are leasing on the properties and how the population benefits from that business in the state.

Boettner adds that larger questions still remain to be answered—questions related to taxation of absentee landowners and whether or not they pay their fair share. He says more research and more transparency is needed so policy makers can do the important work of planning for the future.

Implications and Recommendations from the report:

- The state’s leaders should be committed to establishing fair corporate tax rates that produce sufficient revenue for education and structural infrastructure required to encourage entrepreneurship, tourism, and business development.

- There should be greater transparency in our public records, making it easier for citizens to investigate land and mineral ownership as well as tax rates on such holdings.

- West Virginia’s development dollars should be spent wisely and creatively to promote job growth and build a diverse economy for the future.

- The establishment of a Future Fund (or permanent mineral trust) should not be delayed.

- As West Virginia considers its future, comprehending the role that various patterns of land ownership have played in facilitating some kinds of development and impeding others will be critical in formulating policies that will lead the Mountain State in the direction its citizens want to go.