Poet Writes On Grief, Nature And Hurricane Helene In New Book

Poet Michael Hettich spoke with Inside Appalachia Producer Bill Lynch about his latest book of poetry, "A Sharper Silence."

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

On a warm September morning, ATV riders roll into Matewan, fresh off the Hatfield McCoy Trails. The dirt paths in the backwoods of Southern West Virginia brought Ryan Logue all the way from Kansas City, Missouri.

“The fact that you can just ride your ATVs just right up to the front door here,” Logue said, “and nobody cares if you’re muddy, they just say come on in. And the trails, you really have to see for yourself.”

The Mine Wars was a time of tension and bloodshed in American history when coal miners demanded better working conditions and fair wages. Logue heard about the Mine Wars Museum on YouTube.

“This was kind of a sidestep that we wanted to take,” Logue explained, “just to kind of see this and the fact that we can just write up pretty much right to the front door is just incredible.”

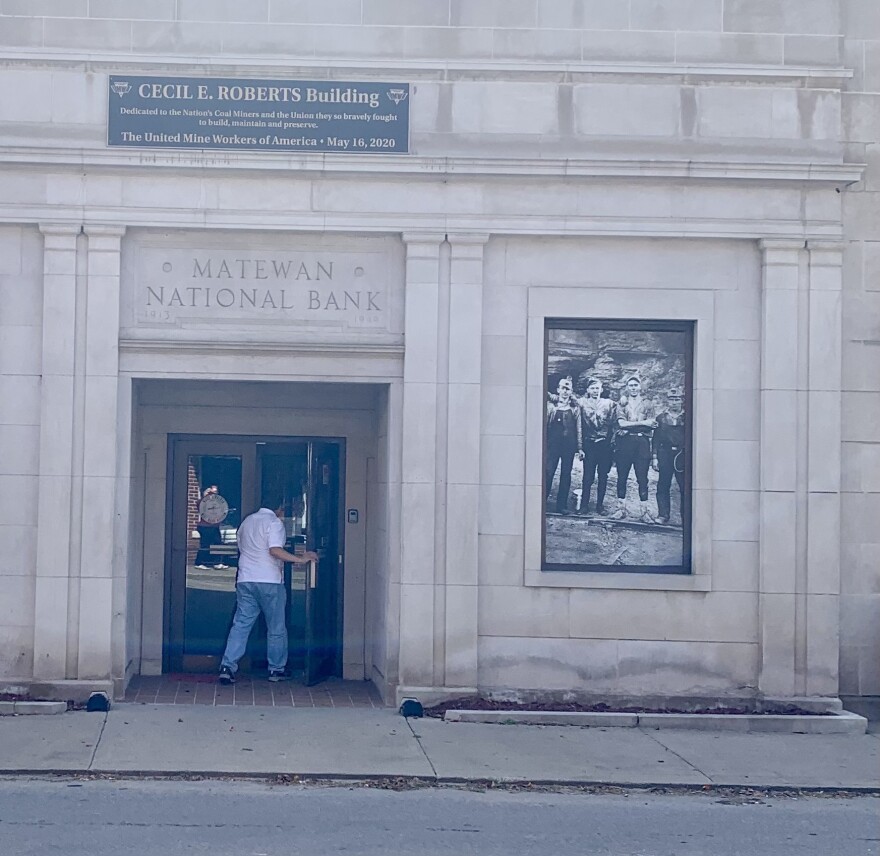

The Mine Wars Museum opened in 2015 in the heart of coal county in Matewan. Last year, the museum moved to a more spacious location just across the street. The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) purchased the building for the museum.

Inside the two front double doors is a display of red bandanas to the left. To the right, is a mural of the museum’s logo, and straight ahead, a petite woman sitting at a desk. A movie poster for the motion picture “Matewan” hangs over her brown hair.

Shop manager and tour guide Kim McCoy was born and raised in Matewan.

“I’m the daughter of a coal miner and the granddaughter of a coal miner, both my grandfathers were coal miners,” McCoy says.

“I was born right up the railroad tracks here at the Stony Mountain coal camp. That’s where I spent my holidays with my grandparents was in an old coal camp house.

“So when my grandfather would talk about the mine wars, you could hear the passion in his story and I remember learning these stories from him growing up.”

Logue and his friends took off their ATV helmets as McCoy guided them through the museum.

“Here in the museum, what you learn about is the Paint Creek/Cabin Creek strike that happened between 1912 and and 1914,” McCoy said. “It was the first time that the coal miners rebelled against the coal company owners on Paint Creek.

“The coal company owners would go up to Ellis Island and would bring in immigrants off the boat. They would promise these immigrants the ‘American Dream,’ but what they got was as close to slavery as you can get without it being called slavery.”

McCoy used that description because everything was controlled by the coal companies. When the immigrants arrived in the southern coalfields, they were given a job doing back-breaking work underground. They were given a place to live – even places to go to church but the workers didn’t own any of it. The coal companies did.

Miners were paid in scrip that could only be used at coal company-owned stores. Often, children were expected to work in the mines.

The notion of working so young sticks with Logue throughout the tour.

“I can’t even imagine at eight years old being told, ‘this is what you’re going to do for the rest of your life and it’s going to be absolutely terrible and we basically own you,’” Logue said.

The museum has a collection of recordings where visitors simply push a button to hear stories from UMWA President Cecil Roberts, and other voices from the coalfields like Grace Jackson, who marched with Mother Jones on Cabin Creek when she was 12 years old.

At the end of the room, a wooden post holds up a wide canvas tent. It’s like the one striking miners lived in after being evicted from coal company houses.

“The living conditions of these people and all they wanted was a chance to just live a fair life and they were just kind of owned by this company,” Logues said.

Along with ATV riders, the museum has hosted elementary and even college students. Bobby Starnes teaches Appalachian Studies at Berea College, where one of her classes is actually called the Mine Wars. Her father was a ‘union man,’ like Kim McCoy’s. To Starnes, the stories of the coalfields go much deeper than a tale of organizing.

“As a teacher of Appalachian Studies, it’s an amazing resource. As the daughter of a coal miner, it touches every corner of my heart,” Starnes said as she fights back tears. “It’s my father’s story. It’s my family’s story. It’s my people’s story. And they tell it with such grace and dignity and beauty.”

Starnes and her students traveled about three hours from Berea, Kentucky, to Matewan, West Virginia to visit the museum. She says it’s been an important part of her curriculum.

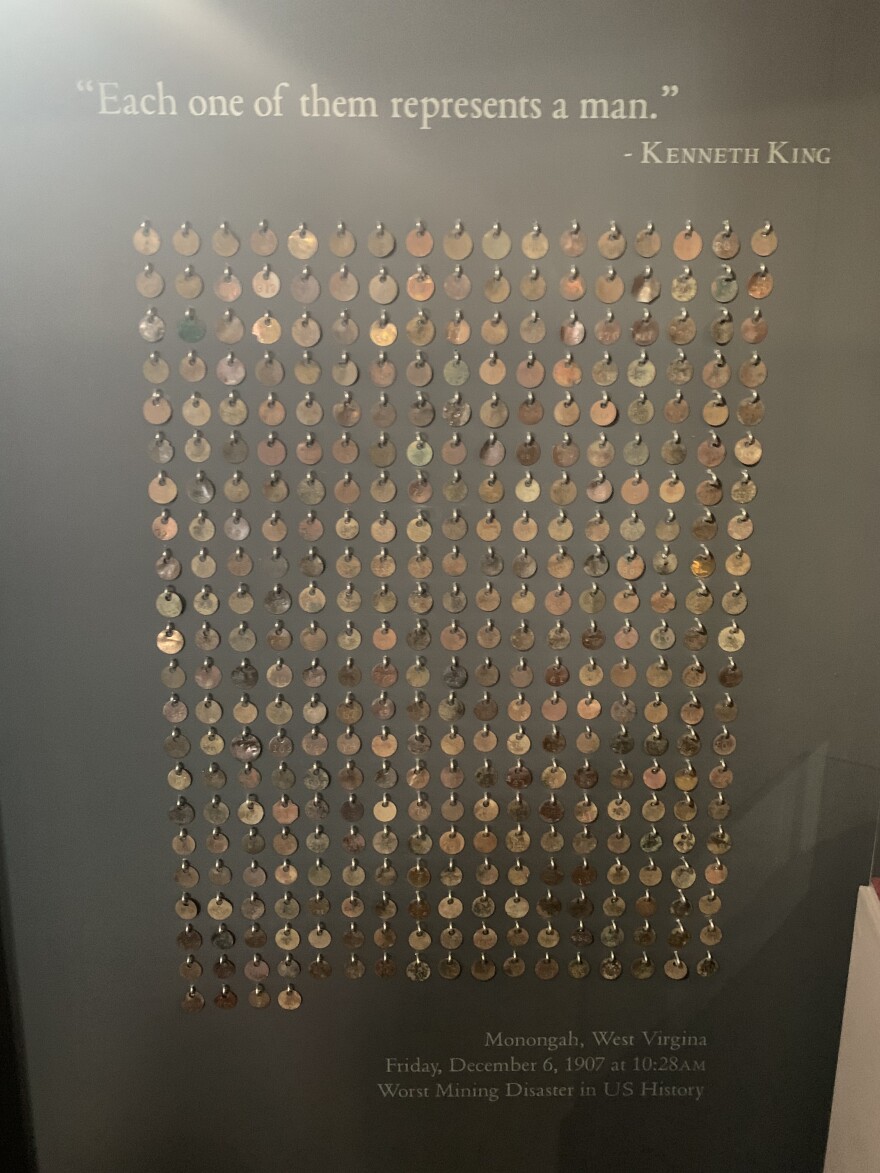

“It just adds so much depth and understanding,” Starnes said. “When you can put your hand on a piece of scrip that some miner was paid with, and know that your hand is on top of the hand that earned that money by going into those mines. That means something. And we talked about the difference between looking at it in pictures and holding it in your hand.”

Starnes even volunteered over the summer to go through newspapers and sources to help with archiving. She couldn’t help but to read them all.

“After reading those stories, it becomes easy to demonize and marginalize people who are, quote, savage,” Starnes says.

“That’s a word that was used a lot in the documents. Part of it is that those stories were stories told by powerful people. I mean, who do you think owns the New York Times? Who do you think owned the major newspapers in the country, it was the same people who owned the railroads, and the coal mines. There is this image of us that is pervasive, and that we have to speak out against and clarify who we really are and what we really stand for.”

The Mine Wars Museum, Starnes says, does just that. It gives context and shares the stories of the coalfields to perhaps give meaning behind some of the behaviors of violence so many years ago.

The Mine Wars Museum is open Fridays and Saturdays 11am to 6pm