LISTEN: Chuck Prophet & His Cumbia Shoes Have The Mountain Stage Song Of The Week

This week's premiere broadcast of Mountain Stage was recorded live at the WVU Canady Creative Art...

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

Reality is more challenging now for people who live at the intersection between substance use disorder, homelessness and the criminal justice system.

New laws across the nation echo aspects of the 2024 Safer Kentucky Act, which enhance penalties for violent crimes, drug crimes, shoplifting and carjacking, as well as a ban on public camping.

On this episode of Us & Them, host Trey Kay returns to Kentucky to check on the consequences of the new tough-on-crime law. In cities, the demand for longterm and transitional housing remains acute, while in small town Appalachia the access to any social safety net can be far, far away.

This episode of Us & Them is presented with support from The Just Trust.Subscribe to Us & Them on Apple Podcasts, NPR One, RadioPublic, Spotify, Stitcher and beyond.

“I’ll be honest—because we’re smaller, we have fewer unhoused people, but there are whole counties without any shelter. It’ll take us a while to sort through the data, but I’m eager to see it because I truly believe the Safer Kentucky Act is harming Appalachians. I remember burning a lot of bridges in my past; sometimes I got lucky and found a couch or went back to my mom’s house, but not everyone has that opportunity. Instead of providing resources or harm reduction, we’re throwing people in jail. Studies show that within the first two weeks after release, some individuals are 39 times, or even over 120 times, more likely to die of an overdose. It’s very frightening for our population with substance use disorder. It’s really scary.”.

— Amanda Hall, Senior Director of National Campaigns at Dream.org

“I hope people understand that many folks are literally living on the street. It’s today’s society—being disabled for so long means I couldn’t work or get a higher disability paycheck. A lot of people fall on hard times and need help rather than being pushed further down the hole. It’s tough, but I’ll push through it.”

— George Wruck, a homeless person living in Paintsville, Ky

“While I have a great deal of respect for the advocates, what they’re doing isn’t working. There’s an industry built around homelessness with a lot of money at stake, and they resist change. I understand that we want people to avoid arrest and jail, but that’s ultimately up to them. It’s easy to demagogue on the other side and say, ‘they made homelessness illegal,’ but that’s far from the truth. If you’re going to break the law and encamp without accepting treatment when it’s offered, that won’t be allowed in Kentucky.

The real question is: What are the underlying reasons someone is homeless? Is it a lack of jobs, mental health issues, or substance abuse? That’s what we need to address. If they won’t accept help voluntarily, we’re prepared to get them before a judge and push for involuntary treatment. We’ll do our best to help our people.”

— Kentucky State Rep. Jason Nemes

“I do have issues with substance use disorder, but I was just released from prison. I became homeless when the person I was staying with had their house burn down last year—when I come home, there’s nothing left. Kentucky was just given $35 million for homelessness services… but where is it going? I have three stage-3 cancers and I’m on the streets, yet I’m asking for help. I’ve followed all the advice, but our lawmakers won’t help.”

— Isaac Chamberlain, homeless person living on the streets in Louisville, Ky

“I’m appalled by the new homeless services division of the police department. Every day, they deploy a huge caravan of sanitation trucks and officers—spending a lot of money literally chasing people around. We know camp clearings increase overdoses—I have data on that—and it’s astonishing that this cycle continues, profiting those who enforce it. Now they want to use opioid settlement funds to pay for the court process our outreach workers and the Coalition for the Homeless set up to handle these citations. I used opiates for 20 years— that money represents the deaths of many of my friends. They’re taking $750,000 from that money to support a court system that exists only because our state passed [the Safer Kentucky Act].”

— Jennifer Twyman, an organizer with VOCAL Kentucky

“The legislation in place today [the Safer Kentucky Act] is not new—it has been used elsewhere in the past. To claim that the struggles within our communities, especially among vulnerable populations, are unconnected is, at best, naive and, at worst, maliciously negligent. No one chooses to live on the streets. The rules that allow some people to remain housed are too onerous, forcing them back outside. This isn’t a matter of choice; it’s a system that prevents people from securing housing. We must address that issue, or decide that everything is set in stone, with no room for adjustment.”

— Donnie Green, advocate for the homeless in Louisville, KY

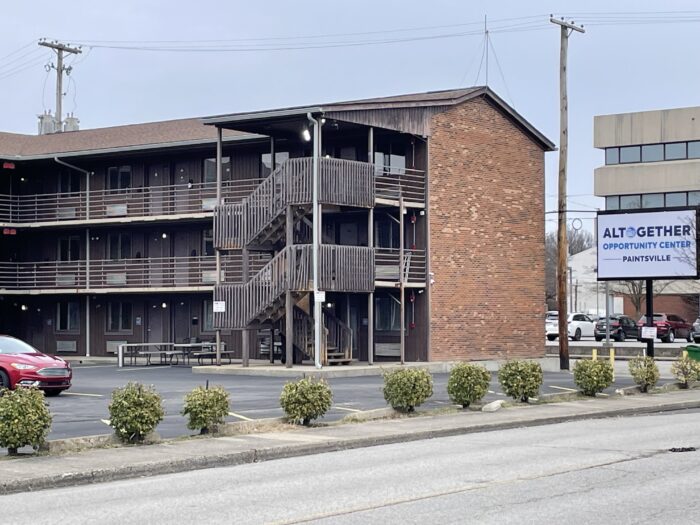

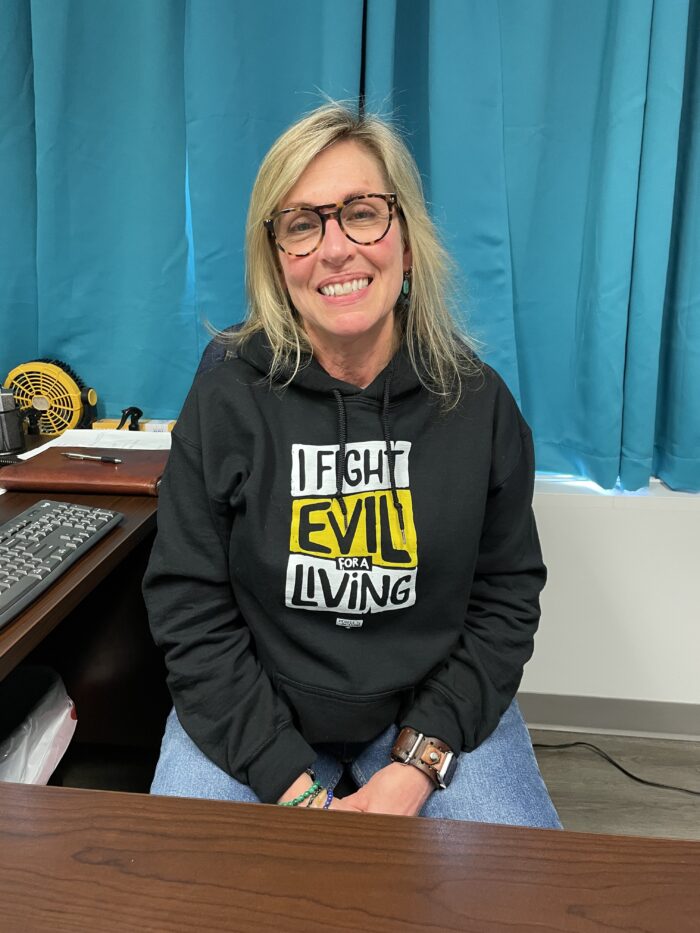

“I often hear people refer to us as the ‘homeless hotel’—or say we have ‘Arthur Street vibes.’ They say negative things about what we do here, and that’s fine—I like to ruffle feathers. What we do is very different. The people we serve have been turned away from every other shelter or organization.”

— Tiny Heron, director of housing services at the Arthur Street Hotel.