Shortly after taking office in January, Attorney General JB McCuskey announced the creation of a new position: director of substance abuse prevention and recovery. And the former state auditor knew just the person to fill that role: a member of his staff who had struggled with addiction himself.

For six years after his painful back surgery in 2013, Josh Barker managed his pain medication well enough to serve as a delegate representing the 22nd Delegate district in and around Lincoln County, run the Boone County ambulance service and hold down a full time position with the state auditor’s office. Then he went through a debilitating series of personal losses.

“I guess one of my biggest triggers was just grief, you know,” he said. “But it was shortly after losing my father, my mom and my best friend and my dog. I guess it’s like a country song… I mean, it was just a bad deal.”

Barker had a stockpile of pills he hadn’t bothered to take. In his grief, he began taking leftover pills and soon his addiction spiraled out of control.

“I went from taking five to 10 pills a week, [to] probably 30 to 40 pills a day or more,” Barker said.

His boss, then-state auditor McCuskey, knew Barker’s job performance was off, but didn’t suspect the reason.

“We noticed that his work was suffering, but … the idea that he was in the middle of very, very active opioid addiction was not in our lexicon. So when his wife called to let us know what had happened, it was an enormous shock,” McCuskey said.

“I thought I was getting Xanax from somebody, and it wasn’t Xanax. It was fentanyl. And I overdosed,” Barker said.

EMTs from the same ambulance service he directed two years before had to administer Narcan.

“Probably the most embarrassing feeling I’ve ever had, when your secret’s out, you know, and everybody knows that you’re a drug addict,” he said.

Until then, Barker said, he didn’t really think he had a problem.

I never once thought that I had a problem. Oh, I’m eating 30, 40 pills a day. But, in my mind, I thought I was functioning,” he said.

For most people, accessing pills from an acquaintance rather than a doctor or pharmacist would indicate a significant problem.

“Absolutely anybody in their right mind [says] ‘That’s a problem.’ Someone in addiction doesn’t look at that as a problem. They look at it as, they don’t want to get sick, and they are trying to just feel better,” Barker said.

He overdosed again the next day in his truck with his wife nearby, and barely survived.

“She expressed me to Boone Memorial Hospital,” he said. “They narcanned me several times there. It didn’t work. I was flown out to Charleston Memorial Hospital. Seven days after that, I woke up on a ventilator… and from that day on, I have tried to right all my wrongs, try to make the world a better place.”

McCuskey – also a personal friend – held his job through the rigors of rehab and recovery.

“When I was on that hospital bed, {McCuskey} said, ‘I don’t care about your job. I don’t care about any of that other stuff.’ He said, The only thing I care about is you, your job will be here when you’re better. JB was a freaking Godsend,” Barker said. “I didn’t miss one paycheck.”

McCuskey chalks it up to a human response to a life-threatening situation.

“I completely understand that not everyone would be in the same situation, but he also never did anything that was fireable because of his addiction,” McCuskey said.

Barker was in an inpatient treatment facility for a month. He got a shot to help manage the addiction for the next 30 days when he left, and a prescription for another dose after that. But when he went to fill it, it wasn’t covered by his insurance – PEIA.

“It was $2,900. My anxiety went out the roof. You know, here I am. I feel like I was protected at that time because of that shot, and it’s going to wear off, and I’m not going to be able to get it, and I’m scared,” he said.

“I talked to the pharmacist about the shot, and he tells me how much it is, and all that stuff. And I looked right at him and told him, I said, ‘Listen, just a short two or three months ago, I was in here getting 120 Percocets and and 60 Xanax, and you all didn’t have one bit of a problem handing me those pills. But when I come in here to get a drug, to get help, there was no help,” he said.

Barker ultimately maintained his sobriety and continued in recovery. That’s how McCuskey, as the state’s incoming Attorney General, realized his employee was in a unique position to help him address an overwhelming problem facing West Virginia.

“It was after the primary, before the general, and I had just gotten off a call with several folks from the West Virginia First Foundation, you know, sort of about how the Attorney General’s Office interacts with them,” McCuskey said.

“And it just sort of hit me that Josh’s true passion was helping people,” McCuskey said. “I was very likely going to be elected into a position where I would have the ability for his passion to match what I think is a really unique challenge, and that is, how do we, as the Attorney General’s office, interact with people in the substance abuse community. His perspective and his experience made him just sort of a unique person in my life to be able to to solve this problem.”

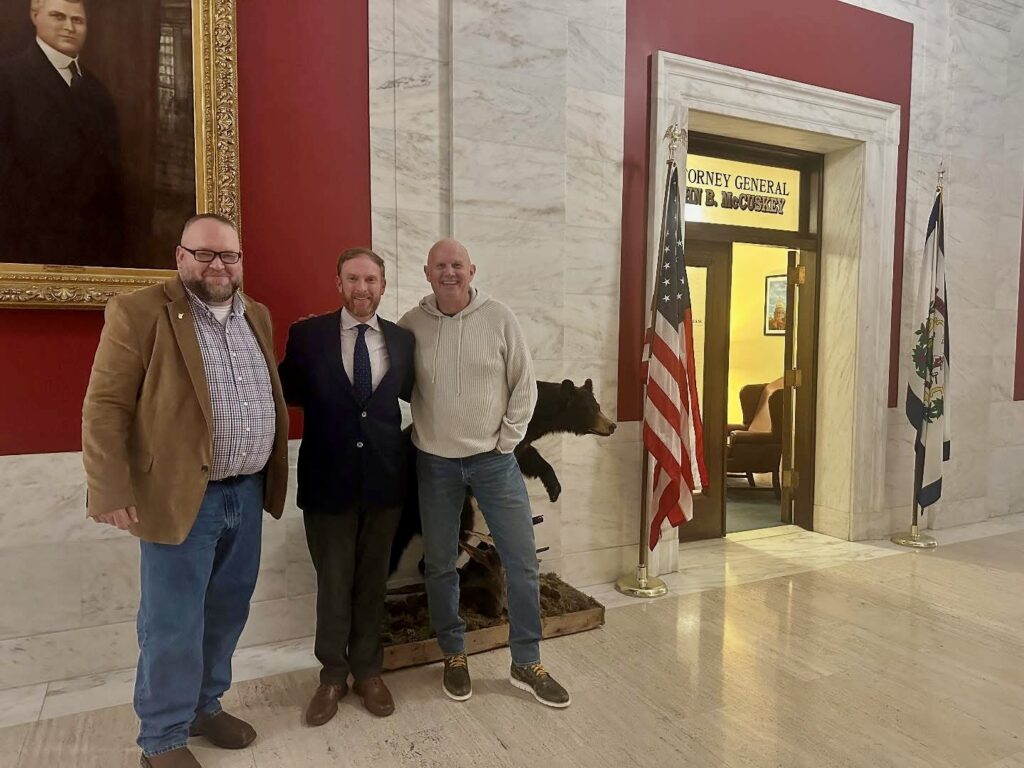

McCuskey created a new role in the AG’s office: Director of Substance Abuse Prevention and Recovery.

“My vision for Josh’s position is to make the AG’s office a place where we can work within all of our local governments and local communities and with the state government to both distribute the funds out of the WV First Foundation appropriately but to also use our investigatory powers, our subpoena powers, to find ways in which the system is failing people.

For Barker, it was a dream job.

“We’ve got almost 1,800 treatment facility beds in West Virginia, and I am touring all those facilities. My schedule is flat full for the next four to five weeks, from Morgantown to Martinsburg to Williamson, all points in between,” he said.

He’s looking for ways West Virginia can improve on its treatment options. He’s also looking at support services for addicts after they leave.

“You go to a 28 day facility, [and then] they throw you out to the road. You’re not going to be ready. You’ve got to have counselors and other support services,” Barker said.

McCuskey is convinced there aren’t enough treatment beds in West Virginia, and concerned that insurance companies aren’t covering treatment for the time prescribed. He also wants to root out treatment options that don’t actually treat.

“What we know is that there are an enormous amount of people who are gaming the federal system and setting up quasi-addiction recovery homes that don’t actually offer services. They’re just extracting money from addicts and giving them a place to live. Those are very, very dangerous,” McCuskey said.

From the darkest of times, Barker has found an opportunity to channel his own experience into a pathway to recovery for countless other West Virginians.

“I’ve been everything from a city manager to a high school football coach to a member of our state legislature, and there has been nothing that has impacted me, like my recovery,” Barker said.

“If I can offer that to every addict in the state of West Virginia, I feel like I would have done my job a million times. Because I feel like if one thing would have went wrong for me, I’d still be in active addiction.”