This conversation originally aired in the March 3, 2024 episode of Inside Appalachia.

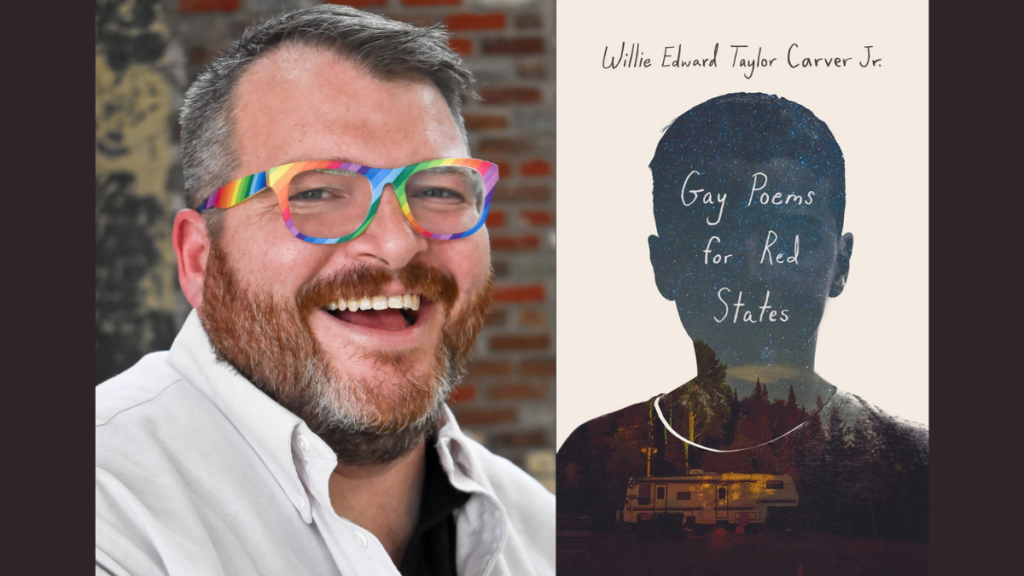

Willie Carver was Kentucky’s teacher of the year in 2021. He taught English and French for 10 years at Montgomery County High School, where he also oversaw several student clubs.

Carver is openly gay. And not everybody was OK with a gay high school teacher. Carver said he — and his LGBTQ students — faced homophobia and were frequently harassed. And so in 2022, he resigned from the high school.

Carver went to work at the University of Kentucky. Last summer, he released Gay Poems for Red States, which attracted a lot of praise and helped turn him into a much-followed, outspoken voice on social media.

Inside Appalachia Producer Bill Lynch recently caught up with Carver.

The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Lynch: “Gay poems for Red States,” it’s a catchy title. But I would say right now the climate for LGBTQ people in Appalachia is difficult, especially if you’re trans. So it kind of feels like you were maybe kind of poking the bear a little bit?

Carver: I don’t want to just poke the bear. I want to rip the blanket off of it and knock the door off of its hibernation den and force it to see what it’s doing.

A lot of what happens, and I say this as someone who is queer and Appalachian, is we want to create easy national categories for people who can’t be put into those things. And so I am just as much Appalachian as I am queer and to choose my queerness, as a general rule, in the United States is to move to a coastal city and then look down on the ignorant Red State people. And I think to choose my Appalachian-ness sometimes would be to see those “high falutin’” city folks as uninterested in my life.

And this title was my way of saying, I reject both of those. I’m going to be exactly what I am. And I want you to recognize me doing it. I want both stereotypes to see me doing it, and question their role and why I’m having to poke two bears, really.

Lynch: You’ve lived outside of Appalachia. What was that like to be an Appalachian away and looking back in?

Carter: So, the funny thing is the first place I moved to outside of eastern Kentucky was France. I lived in Picardy, which is in the far north. There used to be a lot of coal mines. Those have shut down. So, now there’s a lot of poverty, regional accents, and traditional know-how that people sort of share with each other to get by. I was so at home. I was like, I might as well be in Appalachia.

Then, I moved to the deep South and I learned that Appalachia is not the South. It is some version of it, some whatever metaphor people want to use to describe that relationship. But the humor of Appalachia doesn’t translate easily into the suburban south, at least.

I think the free spirit, and the not taking stuff too seriously part of Appalachia doesn’t translate itself very well in the South.

I lived in Vermont. It’s beautiful. It’s where I got married. I’ll always be grateful for that, but it was there that I really saw played out, with me being in the middle of it, this sort of ignorance about people from Appalachia, people from the South; people from rural places in the mouths of supposedly progressive people; people questioning my intelligence; people making these assumptions that I must have had to escape some horrific place. I must be so grateful because everything is better.

I said something online that angered a lot of people. So, that must mean I must have said something close to a truth.

Someone had questioned me and said, “Why would a queer person choose to live in Appalachia? I just don’t understand.”

And I said, “Because it will be easier for me to convince Appalachians to treat me with dignity as an LGBTQ person than to convince coastal liberals to treat me as an Appalachian person with dignity.”

And I think, because we sort of collectively, as a country, group, Appalachian people into a political group, no one feels any guilt about the way they treat people with stereotypes. So, I learned living outside of Appalachia, how Appalachian I am and that the parts of me can’t be divided away for anyone’s benefit.

Lynch: This book comes out after everything that happened in 2022. So how far do you go back as far as poetry? Were you writing before then? Or did the catalysts of being “teacher of the year” in Kentucky and then leaving your job — which came first?

Carter: Poetry came way first. I was always interested in language, interested in how my family communicated ideas. I have been obsessed with linguistics my entire life. But I would hear the poetry and how people talked and wanted to replicate it, wanted to capture it. And in college, I had fantastic professors. I credit them with helping me learn to feel like I was a poet.

Once I became a teacher, I basically wrote for my students, that was what it looked like. So, I wasn’t writing to publish, or anything like that. I really conceived of myself as a teacher — I go into the classroom, and whatever my students need, it’s for them, whatever I’m doing outside of the classroom is really going back to my classroom.

So, I wasn’t thinking about writing. But then once I left the classroom, I felt this strong need to do what I’ve always been doing, which is help students. It’s almost like a parent, watching their kids and the parent is actively trying to take care of them, and then you’re sort of pulled away, and you’re like, how do I take care of them right?

In this case, that meant reminding them how strong they are. And so poetry was a natural way to do that.

Lynch: I like some of your imagery and things you use. You come back to food a couple of times. I think about the cornmeal pancakes and even your description of gravy and beans and things like that. Were you aware that you were drawing from those particular things or did they just kind of turn up?

Carter: I was not aware. One of the things I firmly believe about writing is, if you’re writing a collection, whether we’re talking poetry or short stories, I don’t think you should need to actively tease out a motif or figure it out. I think it’s going to show up, right? And whatever your brain or your heart or your soul or whatever is fixated on. And I think in writing this, I was very angry at the fact that my school was choosing silence when its students were in harm’s way. And I had actually gotten to write an angry letter to my superintendent about how furious I was and ended up writing that first poem.

A lot of what was happening as I was writing was I would kind of wake up and there would be this young child inside of me wanting to write, and I would just let him write about whatever he wanted to write about.

And what he wanted to write about was those times when he felt loved, those times when he felt safe in school and in Appalachia.

And in Appalachia, food is love. So, that’s why food is just this recurring motif, because those were the times when I saw people taking care of me and people loving me.

And I think, knowing that right now LGBTQ youth feel very alienated, feel very unloved, feel like they don’t have a place in Appalachia, feel like they don’t have a place in the classroom, as a general rule. And I wanted to — for lack of a better word — rebuke the educational system. I’m going to rebuke Appalachia, both of which I love, but both of which are failing children miserably right now, because they refuse to wrestle with something that makes them uncomfortable.

Lynch: Would you like to read something from your book?

Carter: Sure. Yeah. “Neck Bones.”

It’s fun to watch kids or respond to this. When I go into high schools and grade schools, there’s usually just a few kids who know what a neck bone is. They get so excited to talk about it or don’t want to talk about it at all. I’ve not had a single in between for neck bones.

(Reads poem)

Lynch: That was awesome.

Carter: Thank you.

Lynch: When did you write that? I mean, I’m sure you’ve drawn from your family imagery right there and your upbringing,

Carter: The way I write … Toni Morrison calls it the flood, but she says, you know, your memories, your emotions that live on your skin. And there will be moments in our lives when it floods back to you, and there’s not much you can do to prevent it.

I’m a big gay Appalachian. So, I got a whole lifetime of feeling strong emotions. I’m not afraid of them. I’m comfortable letting them happen. So what I do when I write is whatever that feeling is, I just kind of let it be and wait for it to start articulating themself. And then, I follow that.

But I think a lot of times people are afraid about what they might call sentimentality. It’s a complicated idea. Because if you don’t want the truth of what you’re talking about to be hidden behind something that’s so emotional, that people are going to feel some kind of way about it no matter what happens.

I think if you center what you’re talking about in your skin, if you center it in the emotions, what you remember, then it’s going to come out in strange ways.

Remembering what it felt like to be loved, for example, meant I had to write about neck bones, because that was how it expressed itself. I mean, I was writing about cornmeal and water pancakes. So, that was how our love expressed itself.

It meant tiny moments of my mom pushing back against whatever ideology, whether we’re talking about Mickey Mouse toys, or whether we’re talking about preachers telling us we’re all gonna burn in hell. Her small acts of defiance, those were things that stood out in my mind as moments of being loved.

Lynch: What’s your life been like since you left Montgomery County High School?

Carter: Really, really good. It was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made. The truth is my presence, because of the way that people responded to me, which is not me, Willy Carver. It’s me, a person who dares be gay and not be ashamed of that. It meant that they were attacking, not just me, but my students. There were people doxing my former students, and those students were getting death threats, because they were LGBTQ.

So, I had to leave because my presence made them unsafe. And what I’ve learned is, I now am a teacher in a classroom with no walls. I have been freed to talk about what I saw in the classroom and how we are harming these students or failing to save them in so many capacities. And that means writing a book, that means working at a Kentucky law project to provide free legal help to students who need support from some outside source. That means testifying before Congress about the needs of Black, brown and LGBTQ students and the ways that we’re failing them. That means getting to meet the president and talking to him about a specific student who needed his help and watching him actually respond to help that student.

It’s funny. I used to say back when I was tired of whatever was being implemented in the classroom, that would require a bunch of outside documentation or work or an unnecessary thing for the teacher to do.

I used to say if ever I won the lottery, I would just go to a library and teach all day. But it would be just teaching. There wouldn’t be interruptions, and there wouldn’t be ball games, or there wouldn’t be having to fill out this in that form or whatever.

That was always my dream. I just want to teach. And now that I’m out of the classroom, that’s what I’m finally getting to do. I’m getting to actually teach. So, I’m grateful. And I’ve met a lot of beautiful Appalachians, and I’m seeing just how good people are. And I think that’s important when you’ve been seeing the ugly for a long time.

Lynch: Do you ever miss being a high school teacher, being at a desk in front of kids?

Carver: Absolutely. I know that I’ve had a very lucky childhood. Even if there were moments of insecurity and poverty, I was loved by the people around me and supported by the people around me. And compared to other gay people, or trans people my age, I’m in the top 1 percent, because the vast majority of people I know, were thrown away by their families.

And so I feel this compulsion because of that, to give back and help. And there is no easier way as a human being that you can know that you are contributing positively to the world, than to tell a young person that their life has worth and that their life has value, and that they deserve to realize their dreams, that they deserve to have whatever it is that they want in life, and that they’re capable. I miss that aspect a great deal and nothing’s gonna replace that. There is no way that you can impact a person’s life in the way that teachers can. But I’m finding other ways to teach and to help and I’m appreciative of that, too.

Lynch: Willy Carver, thank you so much.

Carver: Thank you so much, Bill.