See W.Va.'s Elk Herd This Fall

Beginning in September, there will be twice daily guided tours on most Saturdays and Sundays and will be available through the end of October.

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

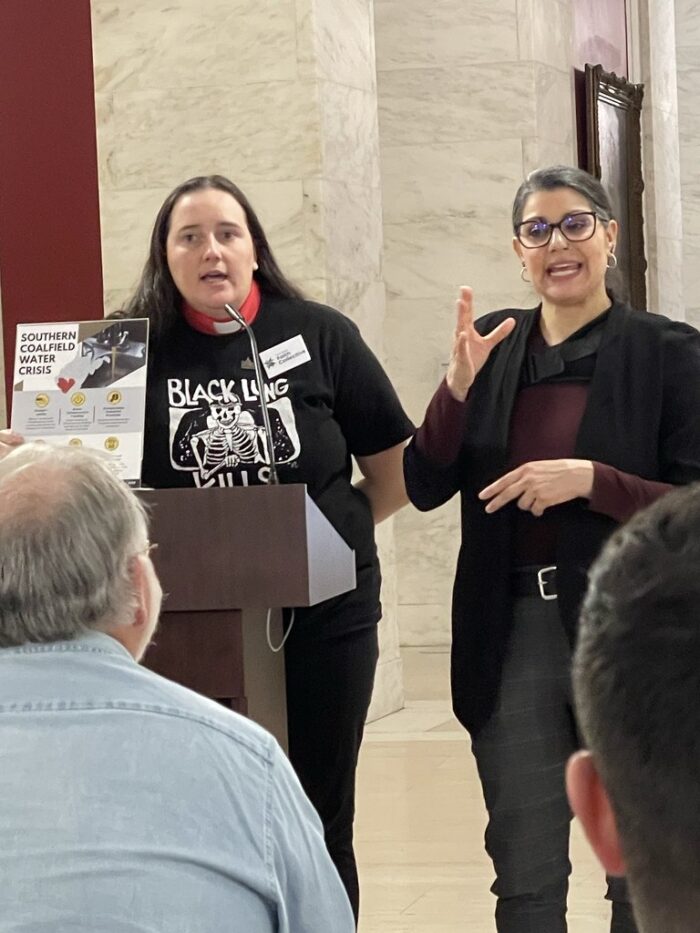

Rev. Caitlin Ware is a United Methodist minister in Jackson County who works with the denomination’s Disaster Response Team. The team has been working for the past 13 months to distribute clean drinking water in small communities throughout southern West Virginia.

Explaining why ministers are involved in water distribution, Ware said, “Water is such a holy gift to us. We use it in our baptism. It’s a way that we remember that we are to resist evil and justice and oppression in any forms that they present themselves. That’s part of our baptismal vows.”

Ware is part of a faith-based group called From Below, dedicated to water and other justice issues for coalfield communities. The group works to make the state government transparent for decisions about where and when to spend money on West Virginia’s water problems in former coal towns. Coal companies once piped clean drinking water into homes within these town limits, but since their departure, the systems need major upgrades. But Ware says the last time the state had a chance to help several small towns get clean drinking water, they didn’t.

“Four hundred and thirty-two million dollars was sent to West Virginia via the American Rescue Plan Act,” Ware said. But out of 161 projects funded with this money, “only four were for water or sewer projects in Boone, Logan, McDowell, Mingo, or Wyoming counties.”

The state created an Economic Enhancement Grant Fund with the rescue plan money. Applications could be for infrastructure, economic development, or tourism projects. Ware thought such legislative actions (prioritizing tourism over infrastructure and prioritizing large towns over small ones) stem from the idea that smaller communities are not the best return on investment. She used an example from McDowell County, the tiny community of Anawalt, population 130 or so.

“If we were to look at getting just that community drinking water and upgrading their public water infrastructure system for 130 customers, it would be in total $11 million dollars,” Ware said.

The investment per person may seem too high a price to pay to legislators, says Ware, but in the town of Anawalt, the citizens are paying for it. Literally.

The United Methodist Disaster Relief Team does a bi-weekly water giveaway in Anawalt. Volunteers Diane Farmer and Peggy Bailey often fill jugs there. Farmer and Bailey are both Anawalt area residents who buy their own drinking water and bear other costs of maintaining access to water.

“Our water is just unusable,” Farmer said.

Bailey added, “When my kids were in high school, you know how touchy kids are in high school with their clothes, I had to go to the laundromat with their jeans and stuff. It would change… all the blue jeans and stuff to the same shade of blue to orange. It stains things orange.”

Farmer said her washing machine, dishwasher, and shower also bear the orange stain. Like many citizens with a private well, she uses salt for its filter. Even after filtering, local well water is undrinkable, usually because it flows through coal seams or abandoned mine works. But it can be used for household cleaning and showering.

To make the well usable usually takes about five bags of salt for filtering, at a cost of $5-6 per bag. Then Farmer and her husband buy gallon jugs of water at a dollar each for cooking. Sixty jugs last six weeks. Since the couple are in their seventies, hefting the jugs into the kitchen is a chore.

Farmer said the cost of getting these jugs isn’t just money. “It’s getting the water into house and then storing it.”

Then Farmer and her husband will buy spring water from local stores for drinking, in 8- or 12-ounce bottles. A case of 24 bottles costs about $3.50. Ten cases last about as long as the jugs of cooking water.

Add in the costs of electricity for operating a pumphouse year-round and keeping it warm enough in winter to prevent freezing. Then factor in that all these costs fall on people in West Virgina’s poorest county, and Farmer and her husband are one of many households paying for and carrying their own potable water into the house.

Ware said this is why she considers that legislative math a cursed calculation: the costs are hidden from legislators. There’s also the fact that many small communities like Anawalt have waited thirty years for clean drinking water to be piped into their houses.

“When is it their turn?” Ware asked.

The length of time people have been waiting, and the pollution levels of the water, is something legislators can’t empathize with, Ware said.

“These politicians don’t know what it’s like to wake up in the morning and get your kids ready for school and when they’re showering that comes out orange. When they get out of the shower there’s gas in the air built up from that shower and there’s rashes on their skin. If you don’t build empathy, and if you don’t build awareness, then we can keep sweeping it under the rug for another thirty years until people have all left.”

Ware and the rest of the United Methodist team plan to continue advocating for government funding of drinking water, but they will also be filling the need until help arrives. They anticipate it will be a long wait, given the costs the state would bear. But she sees no way around the dilemma.

“You’re really just gonna have to fund clean water infrastructure, or we just keep handing out bottles of water until everyone dies,” Ware said.