Morrisey: Tourism Can Help W.Va. Grow

Tourism added $9 billion to West Virginia’s economy last year. And Gov. Patrick Morrisey wants to see that grow.

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

The audio above originally aired in the July 9, 2025 episode of West Virginia Morning. WVPB’s Chris Schulz spoke with students Jessica Riley and Drew Solt to discuss this story.

Read more in this special series from students at West Virginia University’s Reed School of Media.

——

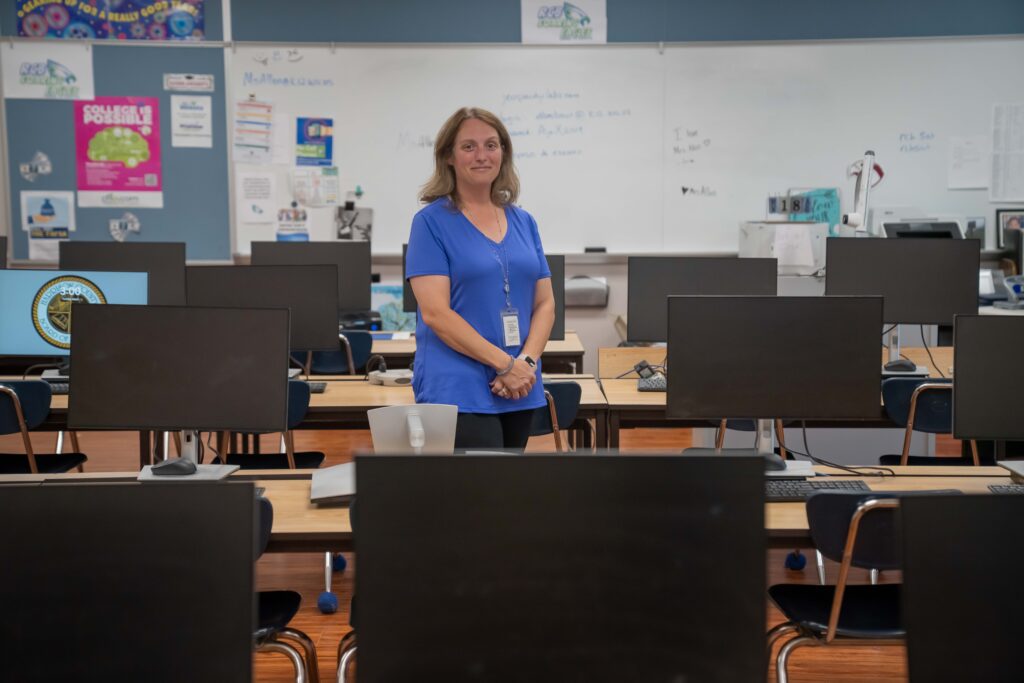

On a Tuesday afternoon, Michelle Allen is in her office in an empty Robert C. Byrd High School (RCB). Allen is the career and technical instructor at RCB and also runs GameChanger, the school’s prevention education club.

In an empty classroom, Allen walks over to a desk where a three-ring binder sits. It contains about 25 pages of materials that GameChanger has provided, including a theme for each month and suggested activities, many of which come from other national prevention education programs, like Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“This year, we were given a framework of each month to focus on a different topic,” Allen explains of the materials in front of her. “I just kind of use Google and research and find things that go along with that message.”

GameChanger is a statewide prevention education program founded in 2018, with the goal of having a chapter in every school in the state by the 2026-2027 academic year. The nonprofit’s founder, Joe Boczek, started the program after his then-college-aged daughter experienced an opioid addiction.

“I know firsthand what families go through when you’re fighting addiction. That was what it was, the impetus behind GameChanger with me,” Boczek said.

According to tax documents, GameChanger is a million-dollar-a-year organization. Their funding comes from the business community, the government and private companies, according to Boczek. But they are also being funded by a new source of money: global opioid settlement funds.

Youth prevention education is one of the seven approved areas of spending of these settlement funds, defined in a 2022 Memorandum of Understanding from the West Virginia Attorney General’s Office.

An analysis of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) responses from 50 of the state’s 55 counties shows six county commissions have put money towards youth prevention: Harrison, Jackson, Marion, Marshall, Mason and Mingo.

So far, GameChanger has received $310,000 from three counties – more than any other existing prevention program – and Boczek said they intend to ask other counties to fund their work from this source as well.

But prevention experts say the program lacks a research-backed curriculum, has no measurable outcomes to show – despite being around for eight years – and may ultimately fail to deliver on its promises to protect young people from addiction. Boczek said he’s willing to listen.

Marion County was the first to award GameChanger opioid settlement funds. The money comes from a global settlement agreed to in 2021 by states, counties and cities across the country who sued opioid distributors, manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies over the nation’s overdose crisis. The settlement distributions will continue over the next 17 years, but as of April 15, Marion County reported via email it has received $960,890.78.

GameChanger’s application for financial support in Marion County came in the form of a special funding request and video presentation given in person to the county commission in May of 2024, according to meeting minutes. Presenters included GameChanger Executive Director Boczek and Lance Puccio, who was representing program Chairman Larry Puccio, a well-known lobbyist and political operative in the state.

After the presentation, the three-member board of elected officials voted to award GameChanger $270,000 to implement their prevention education program in six schools in Marion County over the next three to four years.

Marion County Administrator Kris Cinalli said the county commission asks for proposed activities tied to specific funding amounts in its opioid settlement request form, detailing how GameChanger would spend the allotment. However, in the GameChanger request, the only activity listed is the program itself, with no additional cost breakdown.

According to Boczek, the funding will cover implementation costs.

“We’re right in the midst of figuring out how we’re going to appropriate it. It’s all through the programming, and it cannot be used for anything else other than Marion County Schools,” Boczek said.

Boczek said his program isn’t free, but the cost isn’t consistent across counties or even schools. Some schools receive subsidies from their county board, state or federal dollars, and even support from outside organizations or businesses that help pay for the programming. Just how much it costs each school, Boczek said, is information he is not ready to make public.

Mason County also awarded global settlement funds to GameChanger, but the effort to fund the program was led by teachers.

Tracie Price and Scarlett Enos – Point Pleasant Junior/Senior High School’s GameChanger coaches – along with several students approached the Mason County Commission to request financial support for the program at their school. According to Price, one of the county commissioners is a teacher at the vocational center and talked to Price and Enos about coming and doing a presentation.

Instead of filling out an application for review, like some counties require, Price said the students gave a presentation to the county commission during a regular meeting. The three-person elected commission then awarded their program $10,000.

“They presented a PowerPoint of the things we’d done so far, some of the future goals that they had planned for the following year, some items that we would maybe need to purchase as we went to elementary schools for presentations,” Price said.

According to meeting minutes, Price and Enos have been present with students to give updates on the program to the commission. Price said they have used money to buy swag, a commercial to air during football games, guest speakers’ travel expenses, and supplies for events, like posters. They have also attended events such as the West Virginia Prevention Day at the Capitol and the Mason County Youth Expo.

Before he founded the organization, Boczek worked in marketing. His clients included MVB Bank, which was a corporate sponsor of the West Virginia Secondary Schools Activity Commission. This led to a relationship between Boczek, MVB CFO Don Robinson and Bernie Dolan, the former executive director of the WVSSAC. The three of them came up with the idea for GameChanger together as a way to “get more bang for our buck,” Boczek said.

After its inception and in its first few years, the program garnered key endorsements from several West Virginia politicians, including former governor and current U.S. Sen. Jim Justice, former Sen. Joe Manchin and now GameChanger chair Larry Puccio. Several celebrities have also participated in promotional events and videos later shown to schools, including Jennifer Garner, Brad Paisley, Nick Saban and Tim Tebow.

Most of these celebrities make appearances at GameChanger’s annual Golf Classic hosted at The Greenbrier Resort, owned by the Justice’s family. The $500 individual ticket to the prevention education dinner and golf tournament helps raise awareness and money for the program. GameChanger does celebrate an educator at the event each year; however, no students or other teachers involved in the program attend, according to Boczek. The 2022 Golf Classic cost roughly $470,000, according to tax documents.

GameChanger is described as a K-12 peer leadership program, where older students form relationships with younger kids and help them learn healthy habits. In the fall of 2022, it was piloted in 12 schools in the state.

The teachers and guidance counselors who oversee GameChanger at a given school are called coaches. Coaches work directly with the students to help run events or hold meetings, where many say they show videos about drug misuse and prevention. Coaches are paid an additional $5,000 per year for the position, which is covered by the school district. Each school is also given $500 to use on programming materials and events, which is provided by GameChanger.

Boczek, whose wife is a teacher, said that paying the coaches an extra stipend was important to him because he believes many are overworked and underpaid.

Katie Yeager, a guidance counselor at Lincoln High School in Harrison County, was among the pilot group of GameChanger coaches. Yeager said, even with the additional pay, no one applied for the job at her school.

“They posted it, and no one at our school applied,” Yeager said. “So the principal approached [the guidance counselors] and said, ‘Would you please be willing to be the GameChanger coaches?’”

Yeager took on the role and began sharing videos and PowerPoints created by GameChanger with students, once in the fall and once in the spring during her first year. However, Yeager said she soon realized there is no set curriculum, and it is up to each coach at each school to plan lessons for their students. This leaves most of the work to the coaches, and inconsistencies in programming across schools based on the time and effort each coach commits.

“There’s no real curriculum. We’re kind of allowed to do whatever we feel would be most beneficial for our school,” Yeager said. “The prevention specialist came in and talked with us. They trained our peer leaders, and then we were kind of just left to do whatever we feel is right.”

RCB’s coach Michelle Allen – also located in Harrison County where the county commission awarded GameChanger $30,000 in October 2024 according to FOIA documents – noted the binder with the monthly themes came in her second year of leading her school’s club.

North Marion High School (NMHS) in Marion County started its GameChanger organization in 2022.

“Our group is a student-powered substance misuse prevention group… and our job is really just to educate other students and let them know that not all students are using drugs,” Kaitlyn Knight, GameChanger coach at NMHS, said. “Not all students are vaping. Not all students are drinking. So it’s a peer leadership group that just leads by example.”

But not every student in the more than 700 person school receives the lessons because, much like Lincoln and RCB, they’ve set it up as a club.

“They just sign up. If they think that this would be something that they’re good at and that they like to do, sign up for it,” Knight said.

Superintendent of Marion County Schools Donna Heston confirmed GameChanger is already in three schools – an elementary, middle and high school – in her county. Their implementation came before GameChanger was awarded $270,000 in opioid funds from the county commission in 2024.

“When we first started, we started with a high school because of the design of the GameChanger program, where you have students who are mentoring younger students about avoiding habits or giving them a space where we can get out of some of those generational problems that we have in society,” Heston said.

Ellijah Armour, a 2024 graduate of NMHS, joined GameChanger in his junior year because he wanted to be a mentor for younger kids, especially his niece.

“I wanted to show her a good example of why not to use [substances],” Armour said. “I want [mentor] students to know that their words are powerful to the kids and understand that anything you say could impact them.”

Part of GameChanger’s mission, according to its website, is to help schools comply with Laken’s Law, also known as the Fentanyl Prevention and Awareness Education Act. Passed by the West Virginia Legislature in 2024, the law requires students to be taught about “fentanyl, heroin, and opioids awareness, prevention, and abuse” and Narcan, the name brand for naloxone – a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

According to the GameChanger, 229 middle and high schools and nearly 180,000 students are receiving instruction through the program, but in a spreadsheet made available on their website, multiple schools are listed more than once. Calhoun Middle/High School, with its 400 students, is listed twice, for example. Point Pleasant High School, with its 1,000 students, is listed three times.

When asked for a list of the schools and counties that the program is currently being taught in, Boczek was unable to give a definite answer, saying, “We are currently assembling that for the new school year because more schools are being added, so I am not sure when that will be available,” he said.

Although the research is 20 years old, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reports 80% of American kids participated in some form of prevention education program in their school, but only 20% were exposed to effective prevention programs.

Alfgeir Kristjansson, a professor of social and behavioral sciences at West Virginia University and co-director of the West Virginia Prevention Research Center, said that’s because many of the drug prevention programs that are implemented in schools are there to check a box.

“Schools, of course, are notoriously busy places … and their mission is to educate our kids,” Kristjansson said. “So what tends to happen in these kinds of scenarios is that they will incorporate what is the easiest thing for them to do. And those are usually structured programs.”

Schools have traditionally paid for short-term programs that come with pre-packaged material. D.A.R.E. – Drug Abuse Resistance Education – is perhaps the most well-known of these. Research published in the early 2000s found more than $750 million had been spent on the school-based program nationally, but the program was ineffective – students were no less likely to use drugs after completing D.A.R.E. than if left to chance.

“And then we can check the box. Prevention done this year. Let’s move on to the next thing,” Kristjansson said.

But Kristjansson said effective evidence-based prevention education Kristjansson said can have “enormous” economic impacts. SAMHSA found every $1 spent on effective school-based programs can save $18 on health care and other services later. Kristjansson said it can also delay substance use for young people and reduce their participation in other risky behaviors.

“Kids that start smoking and drinking and vaping and things of that nature later, let’s say at the age of 16 as opposed to the age of 14 or 13, they are also much less likely to drop out of school, engage in teen parenting and get into trouble with the legal system,” Kristjansson explained. “So in other words, there’s all kinds of related benefits from delaying substance use onset.”

Effective prevention education, according to Kristjansson and his experience with international prevention research, is not solely left to schools and educators to handle, but is something that is structurally embedded into a community. He is an advocate of the Icelandic model, which partners with local leaders to identify community-based risk factors and, instead of just teaching kids not to do drugs, works to build healthier communities that support them through the difficulties of growing up and provides them with positive adult role models and alternative, healthy activities.

“The best way to facilitate the initiation of drug use among kids is to give them almost nothing to do and bring very little social support to them,” Kristjansson explained. “There are two major problems that we have in West Virginia. One is what we call lack of parenting. There are just so many kids that grow up in challenging homes and challenging circumstances or with absent parents. And the second is what I broadly refer to as lack of opportunity. There are so many kids in our state that go home after school into nothingness.”

“And in the meantime, while this is happening, they are going through the challenges of puberty,” Kristjansson continued. “We are telling them, go out and take risks, find your own way, do whatever you want. So it shouldn’t be surprising that society is sort of like a grinder. If I don’t provide almost anything to you, surely you’re going to be more likely to engage in risky behavior.”

Kristjansson said he had a few meetings with Boczek as GameChanger was being developed and advised him that the program needed real, research-based prevention.

“I have the utmost respect for him with regards to his ability to market things and to acquire funding and to be visible and out there. He clearly is a very good marketer,” Kristjansson said. “But I told him – I told him very clearly, exactly what I am telling you now – big time bling and rock stars and events are not prevention.”

“To bring in Hollywood stars to do some bling events in town halls, let me tell you what the kids find about these is that this is fun. You’re bringing fun to them,” Kristjansson said. “You bring something like GameChanger through the schools with the logos and the bling, again, it’s fun. It’s a breakup in the day. They will have the ability to move out of a class for a reason. But it has no effect on prevention.”

Kristjansson said there are too many people without expertise getting into prevention.

“Let me just put this straightforward: There is absolutely nothing that indicates that GameChanger is making an impact. Absolutely nothing,” Kristjansson said.

Michael Hecht, a professor emeritus of communications at Pennsylvania State University and president of Real Prevention LLC, said it is uncommon for an individual under 15 to overdose or interact with opioids, but they are not a new topic for youth prevention education programs. There have been questions, though, about what information about specific substances is appropriate for different age groups.

“Opioids are tough because if you’re talking about like a middle school or even a high school, the usage levels are fairly low,” Hecht said.

Hecht created keepin’ it REAL, a drug prevention program that began as a small research project in the 1990s and now reaches more than a million youth annually in all 50 states and 20 countries. The program’s growth led to the creation of Real Prevention, which Hecht said uses federal grants and contracts to create health promotion programs for schools, communities and other organizations working in health care spaces, like the American Cancer Society.

Hecht’s programs use digital tools like apps and video games to address public health issues ranging from substance use to HPV vaccination. His research and resulting programs were used to overhaul and relaunch the D.A.R.E. program that’s currently being used in schools.

“It’s very narrative. It’s about stories, it’s about risk and decision making and social emotional learning,” Hecht said of the new D.A.R.E. programming.

Hecht said research shows programs for young people that focus on social-emotional learning and “develop core basic competencies in kids that tend to make them resilient and healthy” are the most effective.

“They use a prevention theory that’s based on modeling and narratives, and they avoid information fear,” he explained.

Hecht reviewed GameChanger materials and information to provide an analysis of its programming.

“I would never choose a program like that because, I’m not saying that there isn’t a kid somewhere that it won’t help, but if you’re looking to increase your odds about having an effect, this program has got very low chances, in my opinion, of succeeding,” Hecht said.

Hecht said the program relies on pledges and fear-based messages that research has proven don’t improve outcomes for students. GameChanger also has not made public or included in its opioid settlement funding requests details for how it will measure its impact or success.

“It’s not going to move the dial on changing social norms, teaching them social skills, you know, any of the kinds of things that we know are needed for substance use prevention,” he said. “Too many people are marketers or advertisers that get into the field and you recognize their programs as messages immediately because they’re glitzy but have no prevention theory behind them, really, other than fear.”

However, Hecht acknowledged that GameChanger is still a new program.

“I think they’ve come to realize that they need a stronger prevention focus in the messages they’re sending out, that they tend to be kind of glitzy, they tend to fall into that marketing and advertising domain,” Hecht said. “And so they’re likely to maybe capture the kids’ attention, but I don’t know if they’ll go much beyond that now.”

“The reality is, if you don’t have engagement, you don’t have anything anyway,” he continued. “So it’s a step in the right direction. It’s the beginning. But as far as having a prevention theory or something like that, I don’t think it’s really there.”

Boczek acknowledges the critiques of his program’s scientific rigor and said that becoming an evidence-based program takes time – admitting that the process is taking longer than he initially thought. However, he said GameChanger is working to improve.

“If there’s ever been a kryptonite to GameChanger, it’s been an evidence-based question. It’s a working process that you have to cross every ‘T’ and dot every ‘I,’” he said.

Boczek also acknowledged the lack of outcome tracking in the current iteration of the program. GameChanger intends to measure its success by tracking students, he explained. They want to track younger classes until their high school graduation and measure if they use any substances during that time.

Hartley Health Solutions – a health consulting firm whose mission is to “improve community health outcomes through tailored, innovative consulting that addresses the specific needs of underserved-populations” – began working with GameChanger in January to develop more evidence-based programming and potentially help track outcomes. It is staffed by PhDs in nursing, behavioral and social science, and epidemiology.

“When I got to look closer at their materials, I said, if you really want to kind of level up with your programming, you need to develop the science. You need to use behavioral change theories and conduct intervention mapping,” Summer Hartley, the firm’s president, said. “You can work towards encouraging students to have a behavior change, not just education and awareness.”

Hartley said the new programming her team has been developing will be implemented in the fall of 2025 in elementary, middle and high schools. It will be a standard model, she said, that every coach will use no matter the grade level they’re teaching.

“Every coach will be handed an implementation guide, and students will get programming guides,” Hartley said.

“We’re going to be evidence-informed, which is a step in the right direction,” Boczek said of the coming changes.

Boczek said he has also begun conversations with Hecht to help GameChanger move from “evidence-informed” to evidence-based. Those conversations began after both were contacted to speak for this story, according to Boczek and Hecht.

“Dr. Hecht is hugely interested in helping GameChanger because he loves our concept,” Boczek said. “We’ve had two calls with him, and are sending him all our information. He’s pointed out where we need to change a few things.”

“See, we don’t say right now we’ve got all the answers, and we know exactly 100,000% this is what we’re doing. We know what we’ve been able to accomplish, learn it on the fly, and we know what we will accomplish when we continue to associate people with people like Michael Hecht,” he said.

Boczek said GameChanger has been one of the hardest things he has done in his life. His own life experiences around the opioid crisis and the negative effect it has had on the state he calls home are his driving force. He is hopeful his work will leave West Virginia better than he found it.

“I hope that in the next three years, I can step away and see it be evidence-based, see it moving into other states, seeing a very big time staff that’s highly educated PhDs and prevention scientists working every day on the problem and addressing all the new findings, and making sure we keep up with all the new things that may come out that can do it better than we’re doing it now,” Boczek said.

“I hope we’re better tomorrow than we are today. I hope we’re better next year than we are this year, and I certainly hope we’re better in five years than we are now.”

——

Mary Delaney and Zakariah Issah contributed to this reporting.

This story was published in partnership with West Virginia University’s Reed School of Media and Communications, with support from Scott Widmeyer.