Five years after the general populace started using words like “quarantine” in daily routines, questions remain about the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and who needs the vaccines today.

Health Reporter, Emily Rice, spoke with Dr. Steven Eshenaur, the executive director and health officer of the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department, about COVID-19’s lasting impact in West Virginia.

The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Eshenaur: Hello, I’m Dr. Steven Eshenaur. I’m the executive director and health officer for the Kanawha-Charleston Health Department.

Rice: If you could just tell me what capacity you were in. Were you still in the same health department?

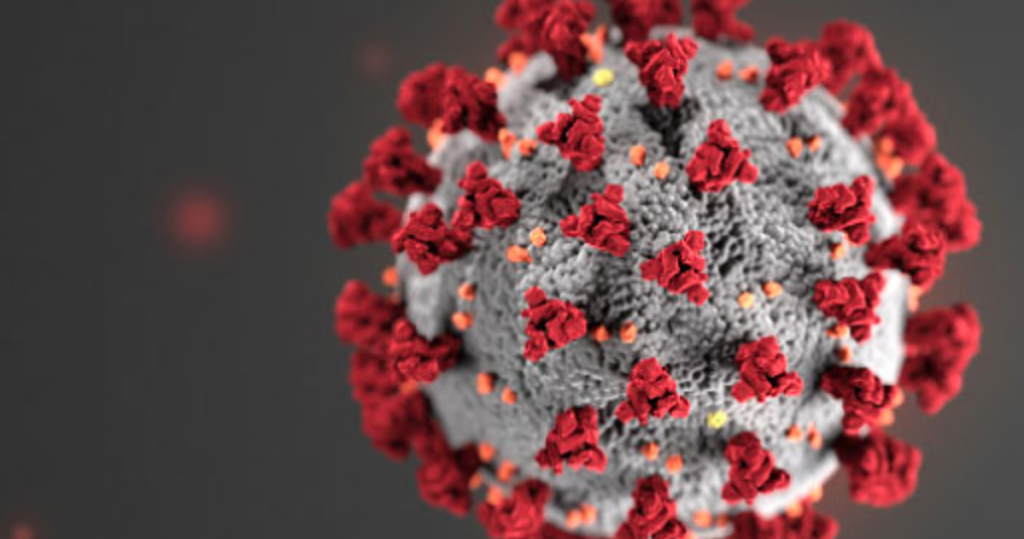

Eshenaur: As a physician when COVID started, I was the director of the emergency department at Jackson General Hospital in Ripley, West Virginia, and it proved to be a very busy and tumultuous time being ground zero of a pandemic. So as we were learning how to protect our staff and ourselves, to how to take care of patients with a relatively new disease, we had seen other Coronavirus family, but not the COVID-19 variant before, and it was very highly virulent, very contagious and caused a significant strain, not just on the emergency department, but the entire healthcare system in the state.

Rice: If you could kind of speak to the vaccine development and how much people were looking forward to it, and then when that sentiment toward medical workers that we are seeing play out in our lawmaking chambers. You know, when did that sentiment come about?

Eshenaur: I can’t say exactly when the sentiment changed, but it appeared to change when restrictions started to come about, reference masking, work restrictions, school restrictions, etc. That led people to want to push back. I think that the mandates for immunizations also caused a significant amount of pushback in those who did not want the immunization.

Rice: Let’s talk about where we are with COVID now? Could you kind of speak to COVID becoming a part of our routine in the health community, when did that sentiment, that feeling, that approach, start to change?

Eshenaur: That was likely in 2023 is when we really started to see the reporting get downgraded from an immediate reportable to a 72-hour reportable, and we started to see the strains of COVID-19 be still highly infectious, or contagious, that is, from person to person, but not as virulent, meaning that it doesn’t make you as sick, kind of similar to some of the other Coronavirus strains that were already in our community. So I think that that really started to turn the corner in 2023. Today, yes, we are still battling COVID. We see a number of outbreaks, particularly in long-term care facilities, where you have patients that are at particular risk due to a weakened immune system, but also you have a large number of people living in close proximity to each other. Immunizations have also changed because as the strains have changed, similar to influenza, we see different strains each season, we also see a similar pattern with COVID, so it’s more likely that we will need an immunization for COVID each year to cover the current strain.

Rice: Could you talk about the medication and treatment that there is, and why is it important to still take COVID seriously?

Eshenaur: Certain individuals are at much greater risk due to a COVID-19 infection than others, and those include individuals that are older. That is our geriatric population. The older we are, we found that the COVID virus was much harder on the elderly. The other group are those that are morbidly obese. For whatever reason, COVID was particularly hard on those with obesity. And of course, anyone with an immune disorder is at risk of almost any disease because they just don’t have enough ability to fight at all. So if individuals are significantly symptomatic and/or at high risk, it is important to seek care from your physician. As far as treatment, we still have the medication, Paxlovid, available. Unfortunately, Paxlovid has quite a number of medication interactions, and may not be taken by everyone, but that needs to be discussed on an individual basis with a provider who is experienced with the medication.

Rice: How did the COVID pandemic prep West Virginia state officials for any possible future outbreak?

Eshenaur: The preparation that came about from being able to not just figure out and practice, but to pull off mass immunization events, many of the counties became very honed and very good at this. That was one element.

Another element is our ability to contact trace individuals that had exposure is probably as good as it has ever been, because all the counties became very good at it. The local health departments, working with the hospitals and other agencies, worked very diligently to contact trace, and notify people of exposure, and then, of course, mass testing events. As you recall, during COVID, we were able to pull off some significantly large testing events for the general public probably never been done before.

So these were all elements that help protect public health and our population by addressing testing, immunization, as well as contact tracing. There’s one really important thing that I want to stress, and that is that during COVID we saw a number of individuals lose trust in public health and in their providers, and a casualty of that has been a loss of trust in childhood disease immunization such as the TDap, or tetanus and pertussis that is whooping cough, measles, mumps, rubella, polio. People were lumping COVID-19 with traditional childhood vaccines that have been around for decades, that have been proven through hundreds of millions of doses given to be both safe and effective.

Look at West Virginia. We’ve not had a case of polio since 1970. You can argue all you want about the immunization, but the fact remains, we’ve not had a case of polio since 1970 and that is attributable to one thing, and that was a vaccine that worked. We have been extremely fortunate in not having measles outbreaks, which are going on now in approximately a dozen states. We have one of the best immunization laws and highest immunization rates for childhood diseases in the country, those laws don’t cover COVID. They only cover our routine childhood immunization.