This story originally aired in the Sept. 10, 2023 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Jeanette Wilson thinks she was about five years old when she heard one of her grandfather’s poems for the first time. Her aunt Edna used to recite them to the children. “She would say them and we’d be cuddled in her bed, like story time,” Wilson said.

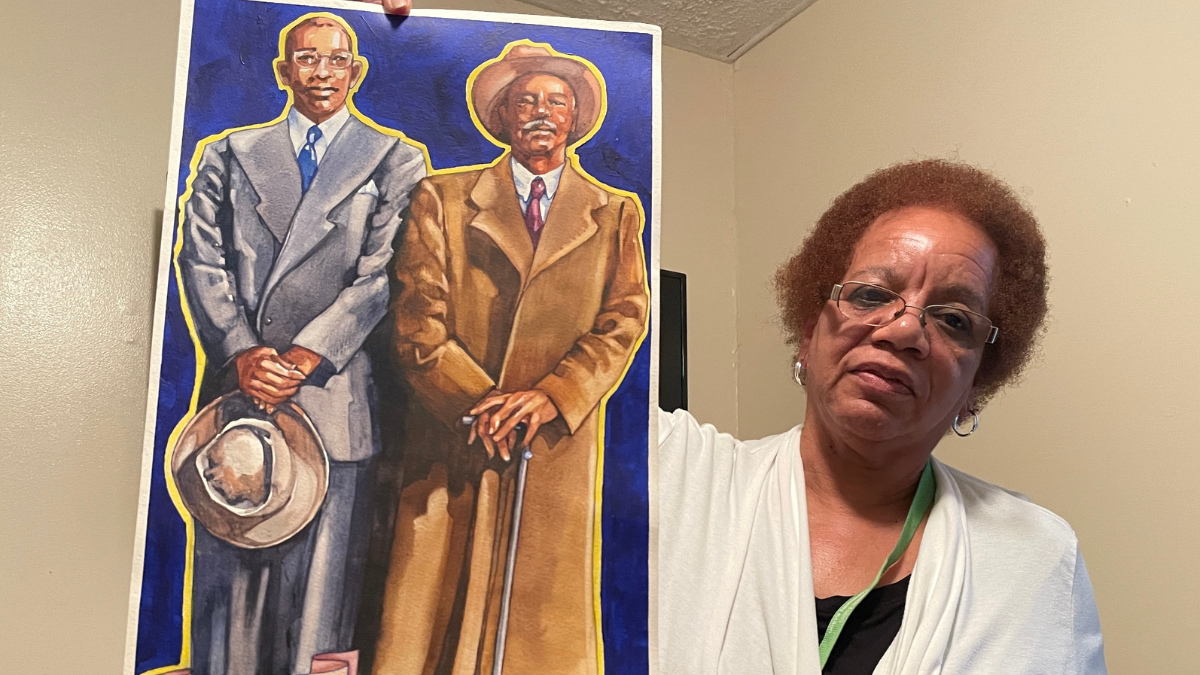

Courtesy Jeanette Wilson

Some of her grandfather’s poems were matched with tunes to make it easier for the children to memorize. “He made up a song, ‘Dickerson Boys Are We’ and it would go something like, ‘All those biscuits in that oven/ How I wish I had some of them/ Sop, sop, the goodness I declare/ All them molasses on that plate/ Something something/ Don’t be too late.’ I can’t remember it all, but they used to sing it all the time,” Wilson said.

Courtesy of Jeanette Wilson

Her grandfather was the Reverend George Mills Dickerson. She called him Papa. He was born in 1871 in Mudfork, a freed slave community near Tazewell, Virginia. He attended Virginia State University, and taught school in the segregated schools for 25 years, at a time when public education for Black students only went to the seventh grade.

Dickerson became an ordained minister in 1898 and preached for more than 50 years. He married more than 1,000 couples at the Tazewell County Courthouse. His ceremony was poetic and often drew courthouse workers to listen in.

Over his lifetime, Dickerson wrote hundreds of poems. He wrote poems about Black children making the long trek to a school in TipTop, about soldiers coming home from World War I with shell-shock, about the development of cities within his region, and one poem about the city of heaven. There were family poems, Tazewell poems, landscape poems and love poems. Themes of his Christian faith were woven throughout.

Courtesy of Jeanette Wilson

Black Community Shares Poetry

One poem, the Outcast Stranger, was about a poor man who found shelter in a preacher’s woodshed before he died. It became a favorite in Tazewell’s Black community.

Wilson says she was shopping one day and ran into a man who asked her for a copy of the poem. “And he told me the story of how he memorized it,” she said. “When he got in trouble, his mom would send him upstairs and say, ‘Now you go memorize one of George M.’s poems.’ And he would come down and recite it to her. He said, ‘Please can you get me a copy, because I love that poem,” Wilson said.

One thing that helped the poetry to circulate in the family and community was that her grandfather copyrighted and published more than 100 of his poems as a paperback book. They were printed by the Hilltop Record, a newspaper company in Columbus, Ohio in 1949. Years later, one of Jeanette’s uncles had more printed.

“I’m so thankful they got these books published,” Wilson said, “because they would have been lost. And it’s our history. You can just imagine how they were doing things from reading the poetry.”

Poetry Tracks History

Joseph Bundy is an African American poet, playwright and community historian based in Roanoke. He said many of Dickerson’s poems provide a historical track of Black life in southwest Virginia in the first half of the 20thcentury. They also show Dickerson’s aspirations for his people.

Commenting on the poem “Black Folks Coming,” Bundy said, “I think he was really way ahead of his time. Instead of saying ‘Negros coming’ or ‘colored folks coming,’ he’s saying ‘Black Folks Coming.’ He was not letting someone else name us. He is naming himself. He’s saying our roots come from Black Africa.”

In the fields of old Virginia.

And on Georgia’s sunny plain.

Africa’s able sons and daughters

Sing a hopeful glad refrain.

They have leaders true and faithful

Men and women brave and strong.

Armed with love, instilled with duty,

Working hard and waiting long.

Douglas struggling up from slavery,

Bruce and Scott, if I had space,

I can name a thousand heroes

Champions of this race.

Bundy said he thinks Dickerson’s poems convey a Booker T. Washington-like philosophy, showing the dignity of all labor. “He’s talking about growing corn, working in the coal mine, and he doesn’t seem to place one occupation or one thing above another. He sees dignity in all of it.”

In the pulpit, in the workshop,

On the railroad, on the farm,

In the schoolroom, mine in factory,

There was power, in brain and arm.

Ignorance shall flee before them.

Hate shall hide his ugly head.

Idleness shall be discouraged

Honest toil shall earn its bread.

Dickerson could write on an everyday level, Bundy said, but also on a high level. “This man, he could definitely write,” he said. If Dickerson had, had more than a local audience, Bundy said, “he could have been like a Langston Hughes or somebody. He could have really been known.”

Credit: Connie Kitts/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Tradition Carries On With Son

Rev. George Mills Dickerson died in 1953. But the tradition of writing poetry carried on with his son George Murray Dickerson. This George Dickerson, who is Jeanette Wilson’s uncle, was born in 1917. He was well known throughout the region for his recitation.

His poems were humorous and topical.

We’ve got a President today,

His name is Richard Nixon.

From what I hear and read about,

This country needs some fixin‘.

Uncle George recited his poems in the public schools, at the community college, local museums, libraries and festivals. He recorded them on cassette tape and made a 45 rpm vinyl single that was sold throughout the community as a fundraiser for the Tazewell Rescue Squad.

Credit: Connie Kitts/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

I’ve always wanted to ride in a Rescue Ambulance

I think I’m gonna try it if I ever get a chance

But I have a couple of questions I’d like to ask you first

Cause some of the folks who ride these things

Wind up in a hearse.

He printed a handful of his poems and sold them as a tri-fold pamphlet. When the town held its summer festival on Main Street, Wilson said, “[Uncle George] would be selling his little booklets, and setting up his little tent and reciting poems.”

Together, the poetry of Wilson’s grandfather and uncle spanned momentous points in African American history. “Papa was right out of slavery,” Wilson said, “and Uncle George’s was right after the Civil Rights Movement.”

Credit: Connie Kitts/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Juneteenth Returns Poems To Broader Community And New Generation

After Uncle George died in 1999, Wilson said the family continued to read his poems – and her grandfather’s, too – at reunions and church events. But the community as a whole began to lose touch with the poetry.

That started to change in 2021. The Town of Tazewell passed a Juneteenth resolution that called for honoring contributions African Americans made to the town and the region. Now, the Dickersons’ poems are read aloud as part of the town’s Juneteenth celebrations.

Courtesy of Vanessa Rebentisch

Bettie Wallace read the poem “‘Cause I’m Colored” by Uncle George at Tazewell’s 2023 Juneteenth Celebration.

Everybody picks on me,

‘Cause I’m Colored.

They don’t think I want to be free

‘Cause I’m Colored.

They won’t give me a decent job,

And claim that I just steal and rob;

And they call me “boy” when my name is “Bob”,

‘Cause I’m Colored…

I thought one time I’d try to pass

And then I looked in the looking glass;

My hopes went down the drain real fast,

‘Cause I’m Colored.

Wallace, 72, said this poem, written in 1973, has special meaning for her.

“I can relate to it so much,” Wallace said. “Coming up, so many things we couldn’t do, not just because I’m colored, but because I’m a dark-skinned colored person. Most of my life people would say, ‘Oh you dark skinned, you can’t do this.’ I did not learn that Black was beautiful until Black became beautiful – that the color of my skin was a very important part of me,” she said.

Wallace said she has known Uncle George’s poetry for years. But now his poems are finding a new audience as well. BrookeAnn Creasy, 18, is starting to write poetry herself. She first heard Dickerson’s poems at the Juneteenth celebration, and she said while they are sometimes funny, they’re also eye opening.

“When you hear poems from other times, like segregation – it makes you understand what we don’t understand. Because I’m a white person. I don’t get to experience discrimination like Black people do. And that’s why I think a lot of people show arrogance, because they don’t like to learn about other people’s perspectives. Because that’s important…empathy,” Creasy said.

Credit: Connie Kitts/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

As for Wilson, she said empathy and equality were recurring themes in her grandfather and uncle’s poems.

“I think they both had the same idea, about life in general for anybody,” said Wilson. “Not just the Black people but everybody – the idea to just have equality for rich, poor, Black, white, you know. Everybody has a part in this world.”

Credit: Connie Kitts/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

——

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia and the Folklife Program of the West Virginia Humanities Council.

The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts and culture.