Christmas Past, Present And Future At Home And Abroad

Two West Virginia University professors discuss the ancient origins of our modern Christmas traditions as well as how people in other countries celebrate.

Continue Reading Take Me to More News

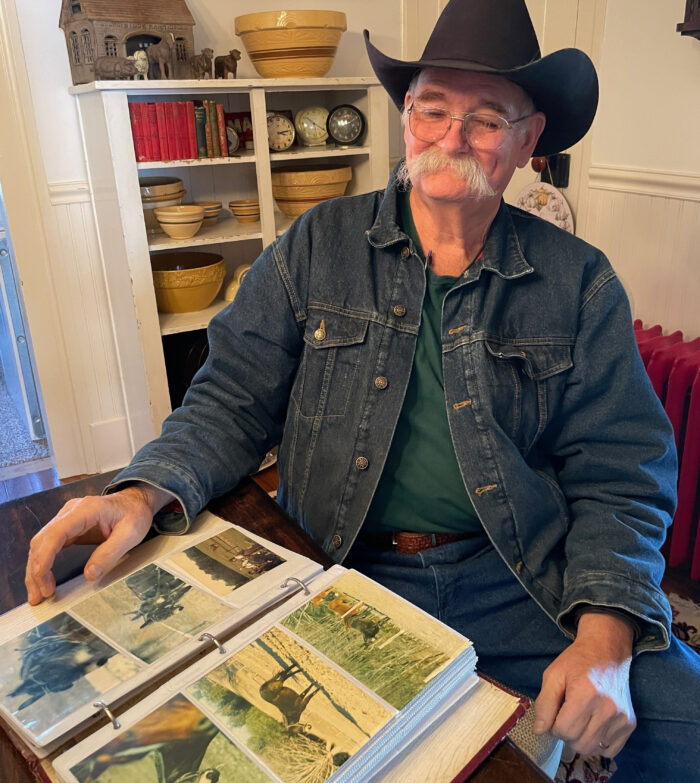

In Wythe County, Virginia, Charlie Burnett lives atop Periwinkle Mountain. “I just want you to see how steep it is,” Burnett says, as he slaps the reins on the hips of Jeb and Rose. “Get up, hup.” The two horses set off to mow a field with an incline of almost 55 degrees.

“My biggest field is four and six acres, and it’s mountain tops,” Burnett says. He grows oats, puts up hundreds of bales of hay, and hauls wood for fuel on the land that has sustained his Scots-Irish family for generations. “This was a farm that you grew a garden. Maybe you grew three acres of corn. That fed the cows that you milked every day,” Burnett says.

There was a time in Appalachia when almost every small family farm had a workhorse, but that changed with the advent of the tractor. Despite mechanization, a few farmers in southwest Virginia never let go of farming with a horse.

Today, more and more people are wanting to go back to that kind of farming. But finding a workhorse that’s like the workhorse of old isn’t easy. And finding someone to train the horse and driver isn’t easy either. Some folks in southwest Virginia are working to save both parts of this old way of farming.

Like Burnett. His family stuck with their horses for safety reasons—not wanting to risk rolling a tractor on land so steep. “We had a team, out of necessity here, not out of nostalgia—we still have to have a team of horses here on this mountainside.”

But the workhorses of Burnett’s youth are harder to come by these days. So, 15 years ago, he started breeding farm workhorses—like the old-style Belgian workhorse. He timed things well. When the pandemic raised concerns about food security, more people started to turn back to traditional farming practices.

Advantages Of Horse Power

In neighboring Grayson County, a friend of Burnett’s, lifelong farmer and regional folklife expert Danny Wingate, understands the reasons why people want to return to this old way of farming. He has always been an advocate for the advantages of horsepower.

“If you’re careful enough to use horses, you’re more concerned about what you’re growing and you’re more in tune to your soil conditions and fertility, and you’re paying more attention, so you grow better food,” Wingate says.

“Most of the time people’s wantin’ to go back to the land, they’re concerned about what they’re eating—where their food’s coming from, the supply of their food, how many chemicals are on what you’re eating,” Wingate says.

Horses don’t compact the soil like a tractor, and the practice of using well-composted horse manure reduces the need for chemical fertilizers, Wingate adds. That’s a soil fertility practice encouraged in the regenerative agriculture movement.

For a small-scale farm or homestead, workhorses also make economic sense. “If you’ve got 10 or 15 acres, why do you need a $60,000 tractor, and that’s not counting the implements that go with it,” Wingate says. And a horse reproduces itself, while a tractor doesn’t.

When it comes to harvesting vegetables, Wingate says horses are efficient partners. Pulling a sled, a team can be directed to keep pace with the workers gathering the produce. “You don’t have to get on and off the tractor or you don’t have to get in and out the pickup truck or wagon,” he says.

“When you’re out with a good team, it’s really peaceful and it’s productive, but it’s also good for you because everything’s quiet,” Wingate says. It’s good for the mind, he says.

The Challenge Of Finding An Old Style Farm Workhorse

The horses that are widely available today lack key traits of a quality farm workhorse. “They’ve almost let the old style horses die out—old style, like being thick bodied and good, quiet manners, and big boned and a slower, more docile kind of horse—easier to get along with, that don’t require as much feed,” Wingate says.

These traits got lost, he says, when many farm workhorses were crossbred to make more of a carriage horse or hitch horse. They became larger, taller, longer-legged, showy horses. And they could sell for much more than a farm workhorse.

“The Belgian horses and the Percherons are a totally different horse than they were even from when I was a teenager,” Wingate says.

And that’s why he was excited about the horses his friend Charlie Burnett on Periwinkle Mountain was breeding.

“Charlie’s trying to preserve a breed of farm horse,” Wingate says. “If you look back in the old Breeders Gazettes from the turn of the century, when they were importing them, the horses that were here then were just like what he’s raising now.”

Practical Considerations For A New Generation Of Workhorse

Back on Burnett’s farm, I had a chance to see first-hand why it was important for a farm horse to be short, sturdy and sweet-tempered. Burnett hands me a heavy leather harness collar and straps, with instructions to swing it over the back of his mare, Rose. She weighs close to 1800 pounds, but because she’s only 16 hands high, even I can harness her—although it took a practice swing or two.

Most of Burnett’s eight horses are about the size of Rose, and it’s a result of his breeding efforts over the last 15 years. In a paddock close to the barn, two broodmares are nursing their foals.

Nearby in a separate paddock, two two-year-old fillies, Roxy and Kate, are already trained to drive and haul light loads. Burnett points out their shorter height and stockiness. “This is what I remember seeing in the mountains when I was growing up and I seen them have workhorses.”

Burnett then strokes the neck of the blue roan broodmare named Gracie.

“Gracie here is just barely 16 hands high. She has huge legs, huge girth. Gracie will weigh about 1800 pounds. So she’s not a small horse when it comes to size but her height–she’s not tall.”

His hope is that her offspring will become the next generation of workhorses, particularly for those wanting to farm in the Appalachian mountains. He points out Gracie’s conformation: a block head and short neck, a short back, wide muscular hips, and stocky legs. “That translates into a lot of power,” Burnett says.

Gracie is an American Brabant breed. The ancestors of this breed came to America from the Brabant region of Belgium in the 1880s. In America they were typically just called Belgians, but in Europe, the Brabant birthplace was often indicated in the registry.

Their bloodlines were undoubtedly in some of the old Appalachian workhorses. But keeping track of bloodlines was difficult.

“There was crosses from all these horses because people weren’t concerned about registry,” Burnett says. “These people were concerned about having a horse big enough to do farm work with and to make a living with and not cost you a fortune to feed….they didn’t have no money.”

When Burnett started looking for this old style breed, he luckily found some American Brabants right here in Appalachia, and started breeding.

As we stand near the horses, Gracie’s colt, Jasper, blinks his long eyelashes. He pushes his soft muzzle against my microphone. “What I am really, really noticing—and it’s really what I like about them—is how docile and how friendly they seem to be,” Burnett says.

And that disposition is critical in making a workhorse your partner.

Passing Down The Art Of Making A Horse Your Partner

While finding an old-style workhorse is the first step of going back to the old way of farming, the other half is learning to become partners with some 1800 pounds of living, breathing horse power, and gaining their trust. Some call it a relationship craft, and both Burnett and Wingate picked it up as boys while working alongside horses with their grandparents and uncles. But Wingate says this training is not so easy to come by these days.

“You can watch everything on YouTube and learn and see how people do it. But until you do it hands-on, it’s a totally different thing,” Wingate says.

Wingate says that training the drivers is probably more important than teaching the horses.

“Really, what you need to do is go somewhere,” Wingate says, “where there’s

somebody that can show you for a while, like a little apprentice program.”

Wingate admired the teamster training schools, run by Amish communities in Ohio, and he visited there often. Even though some of these teachers have died, Wingate still had reason to be optimistic about traditional horse farming practices being passed on.

“One thing about most horse people, they’re really generous with their time and knowledge. Most older people, like me, they really want to see young people succeed. Most people are more than willing to share their knowledge because they see it getting gone.”

Picking Up The Reins To Grow Better Food

One person who was on the receiving end of Wingate’s knowledge is Charlie Lawson, who lives at the foot of Paint Lick Mountain in Tazewell County, Virginia. Lawson’s always been a horseman, and Wingate helped him find his first team of farm work horses.

“I’m learning about this regenerative agriculture,” Lawson says. “It’s basically relearning the secrets the ancient people had.” He says he’s tired of not knowing what’s in the food he’s eating, and doesn’t want to be dependent on diesel fuel to run a tractor.

On a warm day in early spring, I visited Lawson at his farm. He steps onto the seat of a horse drawn riding cultivator,ready to plant potatoes…some 1300 feet of potatoes. “We’re trying something we haven’t tried before,” Lawson says, “which is using a cultivator to open up a furrow.”

That was in the spring and when winter came, Lawson’s family enjoyed dozens of quarts of beets, corn, beans, tomatoes and potatoes—all grown with the help of horse power.

Tribute To Danny Wingate

It was Charlie Lawson who conveyed the sad news to me that Danny Wingate had died, just as I was finishing this story. Local news stations paid tribute to Danny’s iconic role in sustaining local folk arts.

For me, Danny Wingate had brought to life not just the utility, but the beauty of preserving the old ways of farming with horses, and I will remember that for a long time to come.