Gov. Jim Justice’s COVID-19 sweepstakes has captured the attention of many in and outside of West Virginia. That is in part thanks to the campaign’s arguably adorable mascot: Babydog.

The state’s vaccine lottery, and the governor’s English bulldog, have been featured in national news outlets, merchandise, and a song.

No doubt the program has gained some notoriety, which experts say does add to the overall goal of encouraging vaccination.

“Incentives only work if people are fully aware of them,” said Dr. Kevin Volpp at the University of Pennsylvania.

He is not eligible for the guns and trucks West Virginia is handing out, but he has taken an interest in the state’s lottery, and others like it. That is because as director for the Center for Health Incentives and Behavioral Economics, Volpp studies incentives in healthcare.

At this point, he is not making snap judgments on the success of any program.

“We’ll probably have an answer to that relatively soon. But it’s still a little bit early to say,” Volpp said.

The state’s program has cost taxpayers $10 million. Of the roughly one million residents who have received one dose and are eligible to enter the lottery, only a third have actually registered.

West Virginia and other states like Kentucky and Massachusetts are still doling out prizes. Volpp says to fairly assess how effective any state’s program is, you have to see what happens when the extra incentive goes away.

“We really need to understand what is the effect of each of these programs, relative to what would have happened had the programs not been put in place,” Volpp said.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1626361230382’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’727px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

West Virginia’s vaccine lottery lags behind others

It gets a little complicated to project what would have happened. So let’s start with what has gone on thus far.

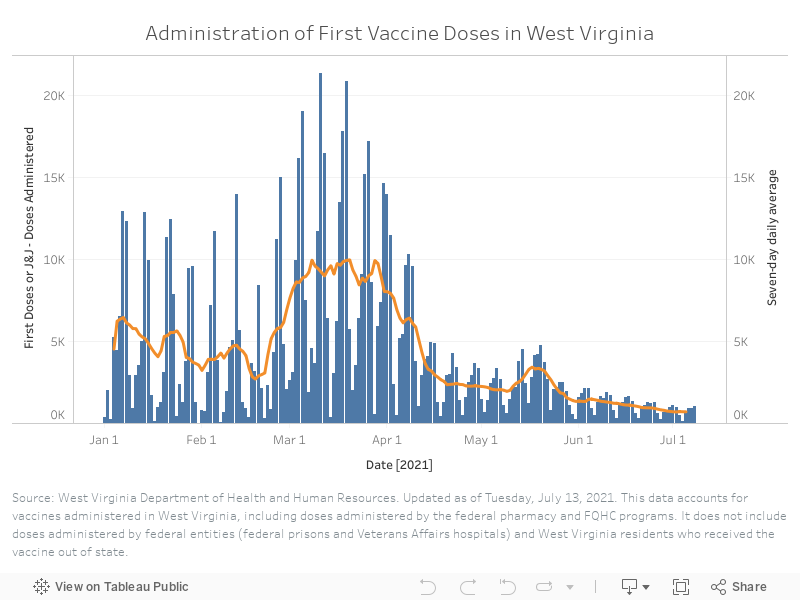

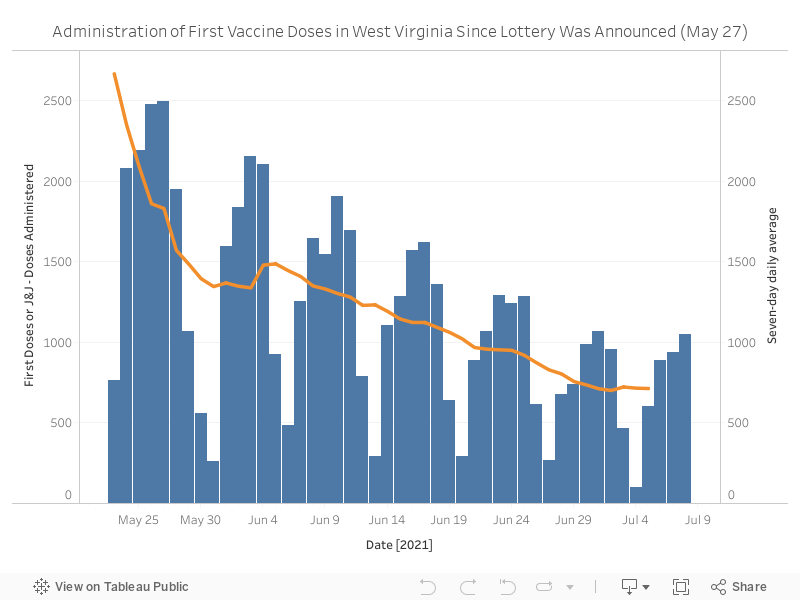

Since Gov. Jim Justice announced the lottery in late May, vaccinations have steadily declined. About 2,500 people a day got newly vaccinated in the few days before Justice’s announcement. Now, about six weeks later, that number has fallen 70 percent, according to data from the Department of Health and Human Resources.

Out of all 50 states, West Virginia ranks 40th in percent of population fully vaccinated at almost 40 percent.

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1626359296061’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 800 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else if ( divElement.offsetWidth > 500 ) { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=(divElement.offsetWidth*0.75)+’px’;} else { vizElement.style.width=’100%’;vizElement.style.height=’727px’;} var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

That’s a very different outcome than Ohio’s Vax-a-Million lottery. The state saw a noticeable, though short-lived, bump in vaccinations. (Same goes for New Mexico and California.) Ohio saw a 33 percent increase in vaccinations the week after Republican Gov. Mike DeWine announced the lottery.

But researchers disagree on whether or not the lottery was the reason for the increase. A recent study out of Boston University attributes that bump to those who are newly eligible.

“You wouldn’t want to have the lottery take credit for an increase in 12 to 15 year olds,” said Volpp. “That’s an example of some of the types of confounding factors that one has to account for in these analyses.”

West Virginia’s lottery is set to wrap on Aug. 4. Prizes will have been given out over the course of six weeks.

But lotteries that start and end later than others are bound to show less results, said Katy Milkman, a behavioral scientist teaching at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Frankly, there’s less low hanging fruit in terms of people who just haven’t gotten around to it,” Milkman said. “The longer you wait, the more you get into the hardline, ‘I’m really not interested’ or ‘I’m really against this’ group, and they’re harder to persuade.”

The next incentive program

Milkman helped build Philadelphia’s “Philly Vax Sweepstakes,” which includes a “regret lottery” where an unvaccinated person may be chosen to win but they are unable to claim the prize. The University of Philadelphia-run program will also examine the impacts of the incentive, while prioritizing zip codes that have lower rates of vaccinations. Both the city and the state of Pennsylvania vaccinated 70 percent of its residents by late June.

When a vaccine was on the horizon, Milkman realized there should be mechanisms in place to encourage people to get the shot. She was impressed with how quickly vaccine manufacturers and the federal government were able to make a vaccine available to the public. She thought the campaign to get folks to accept the vaccine was lacking.

“I wish we had done a bit more to lay the groundwork. I think we’re scrambling a little bit right now more than we should,” Milkman said.

West Virginia is a good example of this. It led the nation initially in the vaccine rollout due to its use of the state National Guard, while other states had to play catch-up. As supply began to outweigh demand, West Virginia fell to the middle of the pack and then near the bottom.

Experts like Milkman say there are other ways to convince people to get the vaccine, and that a single approach could never cut it.

“If somebody is really dead set against it, that needs to be a conversation, not a cash payment,” Milkman said.

Some states have rolled out programs to start these conversations Milkman mentions. Maryland and Florida have hired health promoters, or “promotoras,” to engage with the Spanish-speaking population, who are getting vaccinated at lower rates than whites.

Volpp brought up vaccine passports, or mandates. It is the idea that institutions and private businesses can require participants to get vaccinated. That helps assure administrators that the virus will have less opportunity to spread in the school or workplace. Personal perspective defines whether this sounds like a ticket to more normal activities or a coercive mandate.

If vaccine requirements prove successful, they could positively impact vaccine rates across the state. Experts point out that making a vaccine mandatory, as some schools have done, requires little funding, unlike big cash giveaways.

“More than 400 colleges and universities have said if you want to be a student living on campus, attending in person, you need to be vaccinated,” he said.

For these students, Volpp says being on campus, living in a dorm, and interacting with peers is paramount to the college experience, which can be a huge motivator.

“It’s certainly a lot more important to me than getting $100, or a very small chance at a lottery. It relates to my being able to live my life in a manner that a college student wants to,” he said.

Dave Mistich produced the graphics for this story.

Appalachia Health News is a project of West Virginia Public Broadcasting with support from Charleston Area Medical Center and Marshall Health.