Stanley “Goose” Stewart worked as an underground miner for Massey Energy at the Upper Big Branch mine for 15 years and in all of those years, Stewart said production came first, no matter what the conditions were underground.

“There was an element of fear, intimidation and propaganda working there,” Stewart said in Charleston federal court Tuesday. “We knew if we didn’t [produce], we would be fired, or they would harass you until you quit.”

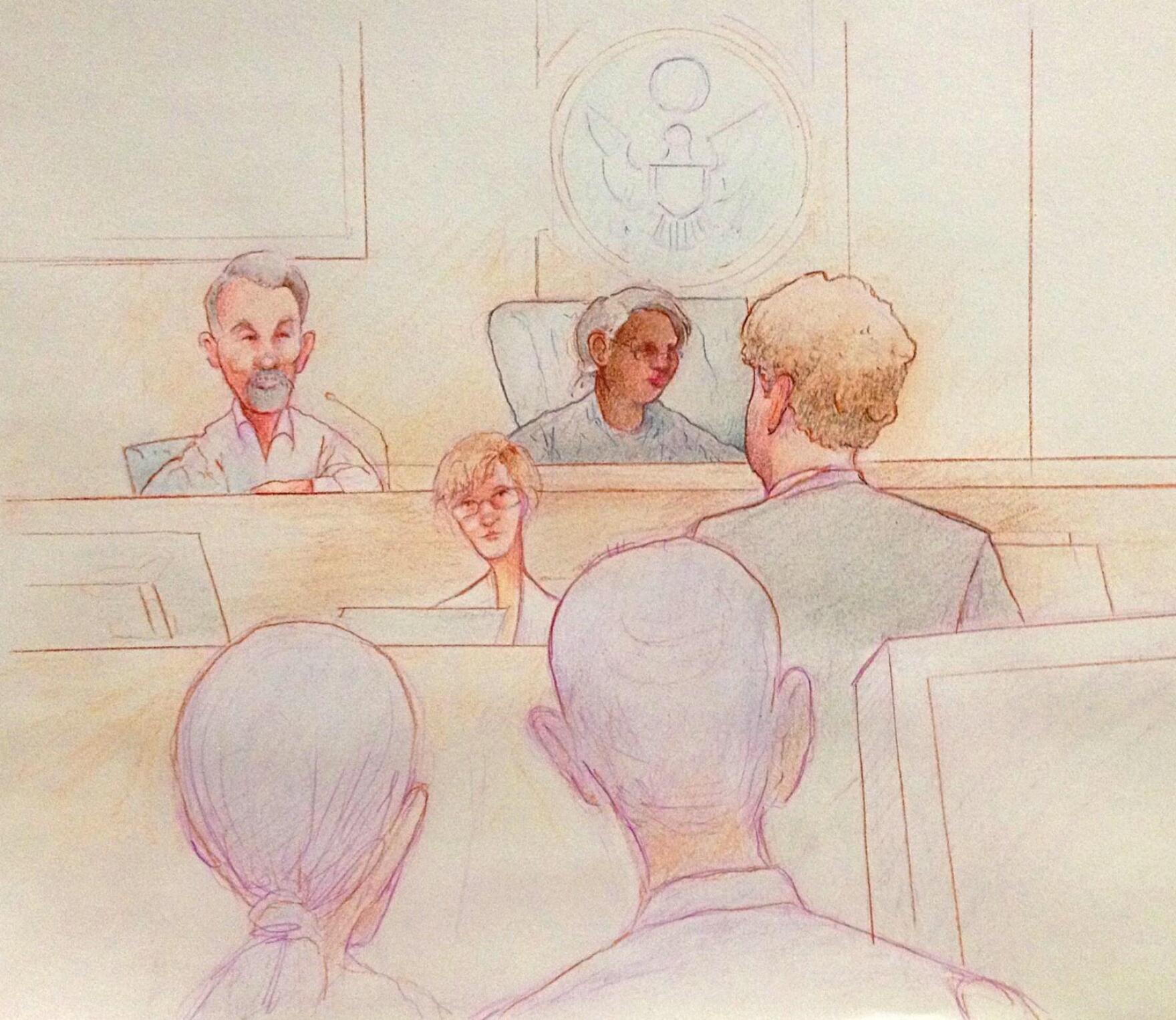

Stewart was called by the U.S. Attorney’s Office to testify in the trial of former Massey CEO Don Blankenship.

Blankenship is charged with conspiring to violate federal mine safety standards and lying to securities officials and investors after the Upper Big Branch mine disaster in 2010 that killed 29 men.

In his raspy, southern West Virginia accent, Stewart painted a picture for jurors of a mine with excessive amounts of coal dust and little to no air flow that, according to him, was never properly rock dusted, a mine practice that helps prevent explosions.

“Why did you engage in unsafe conduct?” U.S. Attorney Booth Goodwin asked him during direct examination.

“I had to. The pressure was to produce coal at any cost,” he replied.

Stewart described for the jurors a “code of silence” between miners working at Upper Big Branch, miners who didn’t report the unsafe conditions and cleaned up sites quickly when they were given advanced notice that a safety inspector was on site.

The veteran miner said he reported issues once to a state inspector he considered a friend, trusting the inspector would keep his compliant anonymous so it “wouldn’t get back to the company.” Under federal law, miners are afforded a guarantee of anonymity when reporting issues to safety inspectors, but that was something Stewart admitted he did not know at the time.

Prosecutors walked Stewart through a 2008 agreement he signed with Performance Coal, a Massey subsidiary, giving him a raise in exchange for a guaranteed minimum of three years of work at the company. That agreement, however, did not prevent the company from firing miners for any reason and mandated miners repay their full salary increase should they be fired or leave the company before the end of their three years.

On cross examination, defense attorneys attempted to depict Stewart as an opportunist, working with the United Mine Workers of America to book a speaking engagement after the UBB accident, testifying before Congress, conducting media interviews and speaking with a CBS News representative during Tuesday’s lunch break.

When asked by prosecutors why he had been so outspoken in the wake of the mine disaster, Stewart broke down on the stand.

“I felt like the truth needed to be told,” he said. “I wanted the truth to be told, that they had a code of silence there. They (the miners) felt afraid to speak up and I wanted the truth to be known.”

On April 5, 2010, the day of the explosion, Stewart was 300 feet underground at UBB on his way to begin his evening work shift; however, Stewart did not talk about his whereabouts during his sworn testimony.