In 2022, Berkeley County celebrated its 250th anniversary. Now, the county is looking back at its history through a public art lens.

By early June, a mural will be on display in the heart of Martinsburg tracing the history and culture of Berkeley County over the years.

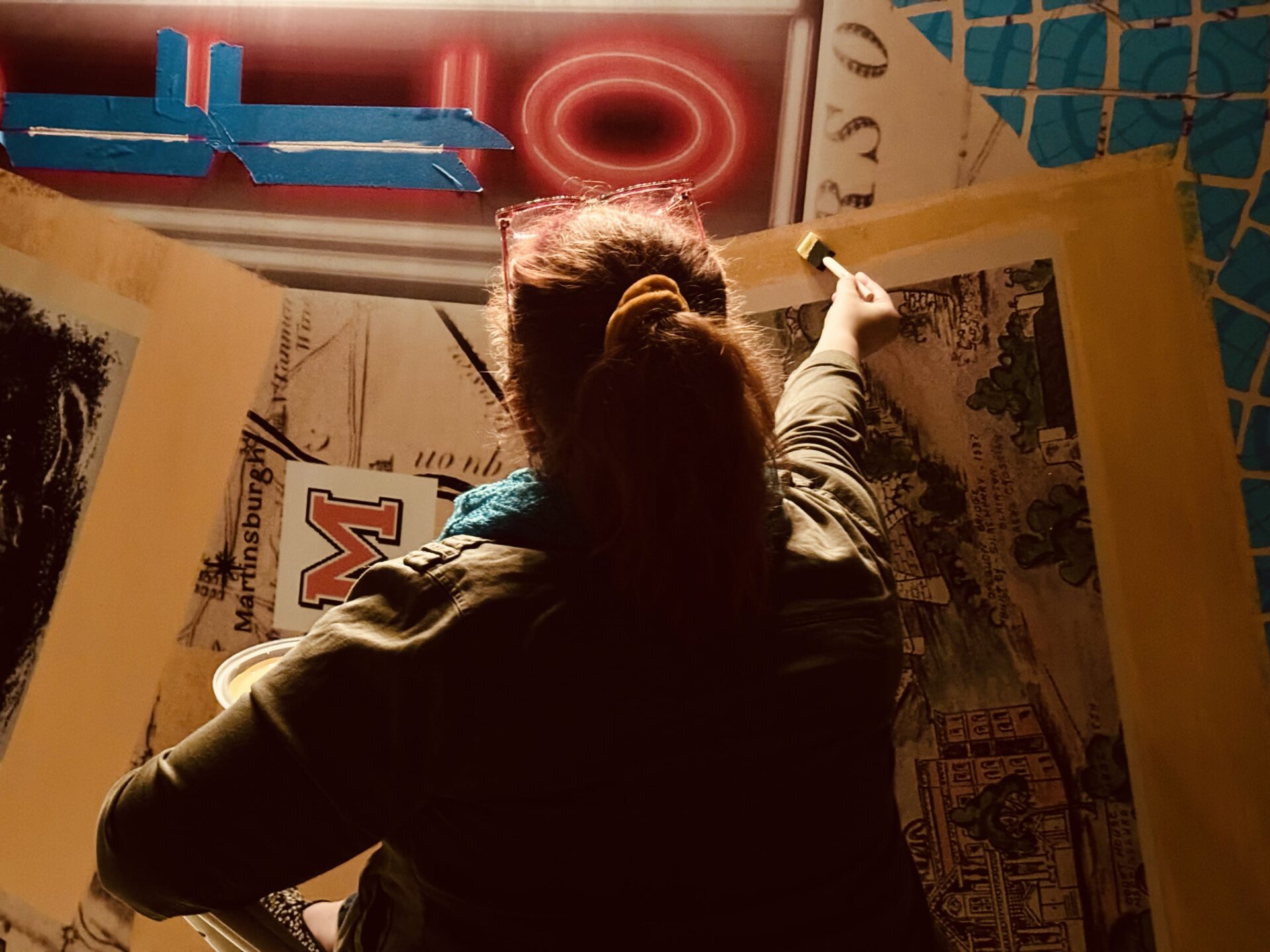

Reporter Jack Walker spoke with Lea Craigie, the artist behind the new mural, about her public art piece so far. Craigie grew up in Martinsburg and attended Shepherd University as an undergraduate.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Walker: To begin, could you tell me a little about the mural project you’re currently working on?

Craigie: Yes. So I was contacted by the 250th Commemoration Committee for Berkeley County to create a mural depicting a lot of the history that we don’t really necessarily learn about. A lot of it was very new to me, even though I did West Virginia history in school — and, you know, you learn a lot. A lot of the history that I dug up and found to include in the mural was history that I think a lot of people just won’t know about until they maybe go to the mural and start looking at all the details.

Walker: What are some of these aspects of history that you’re speaking about that are going to be featured in the mural?

Craigie: So a lot of the arts and the agriculture and things that we do know about in Berkeley County and we’re proud of are highlighted. But then also just hidden figures. So one of the panels of the portraits of people is Garland Lorenzo Wilson. And he was a jazz pianist in the 20s, an African American man who made it on his own. It’s just an amazing, inspiring story of a musician who made it. He ended up going to Paris and playing with all the jazz greats. So he is one of the portraits that’s highlighted, and he’s definitely somebody I never knew about before. I love unearthing figures, especially of people in history I just never got to know about.

And I just wanted to make sure I highlighted somebody that maybe we didn’t know about yet, who came from Martinsburg.

Walker: And I know that this is going to be a pretty massive display. Could you tell me a little bit about what went into the location of this mural, and then also what this mural will look like in terms of size and scale?

Craigie: The building that this will be located on is on Water Street in Martinsburg.

And it’ll be seven 10 foot-by-10 foot panels depicting the arts, the agriculture, the industry and figures and also, very importantly the airport. The airport was a really important hub for Berkeley County.

Photo Credit: Jason Marshall

Walker: So it sounds like both in terms of the content of this mural and then also its placement very prominently in Martinsburg that this is something that’s kind of trying to very publicly state that these are pieces of Martinsburg history, and kind of honor things that are unspoken in terms of the Martinsburg narrative. Is that true to how you see this project?

Craigie: I believe it touches on every aspect of Berkeley County. I’ve worked very hard to make sure all parts of the community and all parts of the county were depicted in the mural. So in the industry panel, we have Musselman Apple. So every part of the county. I went from Hedgesville, to Musselman, you know, to all the different areas of the county. And actually the county at this point in history, it goes from the beginning of Berkeley County, to the end. So as you’re looking at the panels, the very first panel in the background of the arts panel, is the outline of Berkeley County as it was at the beginning. So Berkeley County actually went all the way to Berkeley Springs, which is why Berkeley Springs has its name, Berkeley Springs. And then it shows at the end panel on the industry panel, it will show the outline of Berkeley County, as it is today. So different boundaries, and then what those boundaries contained, and the history they contained, which is vast. And through every panel, at the bottom of every of the 10 foot panels, you’ll see a blue ribbon of mosaic tiles that actually represents the Opequon. And so the Opequon River runs through the entire county from start to finish. So it runs through my entire mural from start to finish. So it also shows the ecology of the county as well as the history.

Walker: And what’s the community response been like to this project so far?

Craigie: So far, wonderful. They released the press release. And the feedback has been great. And people, I think, are very surprised. And we’ve kept it very quiet until this moment.

Walker: As a closing question, I’m just curious: You’re someone who grew up in Martinsburg, grew up in Berkeley County. What does working on a project for your home county mean to you?

Craigie: It means so much. Personally speaking, it just means so much to be able to have this hanging in Martinsburg for years to come, decades to come. And to know that I was able to gift it to the community. I don’t see my murals as my art. It’s my gift to whatever community that art lives in. So to be able to gift my hometown community with my art is just — I don’t really have words. It’s very, very profound and exciting to me.