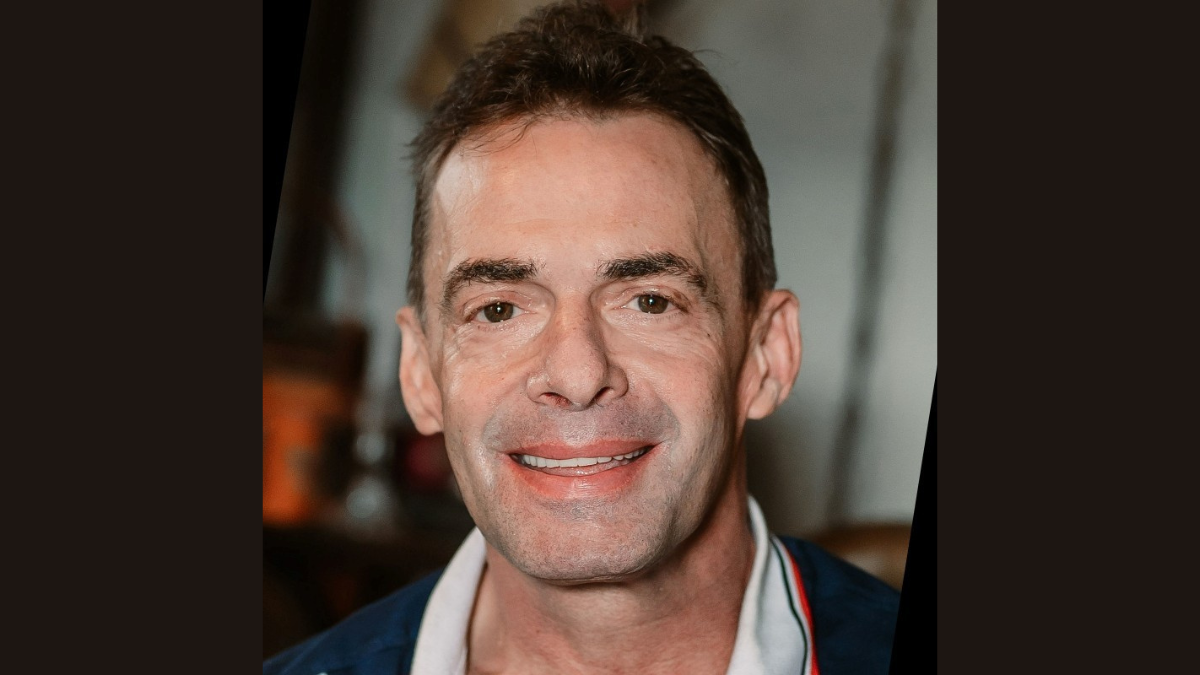

John Michael Cummings is an author in Harpers Ferry. He’s published three novels, two novellas and many short stories. Cummings recently spoke with Bill Lynch about writing and his latest collection of short stories, “The Spirit in My Shoes.”

The following has been lightly edited for clarity.

Lynch: Would you like to start with reading something?

Cummings: Yeah, let me see. Yeah, here is an excerpt. This is kind of a prose-y essay piece. It’s from “Crows and Sparrows.”

In divorce, the gods dropped you from their laps, and the forces of the inevitable and adverse nudge you into the unknown, oblivious to your whimpers. Before you can protest or brace yourself, another source of harm and ruin shoves you into the body of the stranger beside you, so that you yourself become that stranger, first to the world, then to yourself. Alone, you wander into the forest of alienation, where strangers introduce you to the age of self-help, Zen, and yogic self centeredness. Although you strive to attain mental well being, you, just too angry for enlightenment, feel too discontented and rebellious. Or you seek spiritual elation through sex and food, but receive only disillusionment, the return of hunger and another day. It cannot suppress the scorn lacing your mind and will. You cannot unearth your good, kind self. Instead, shame and guilt hammer against the inside of the head. Or consternation vibrates through your ribs tingling up to your fingertips.

That fight of your life is on.

Lynch: Tell me a little about that piece.

Cummings: Well, it’s sharing some of the intense feelings that are personal and were lived by me, experienced by me, and that are in some way, trapped inside me. But they are singular to me and alone with me and remote with me. So by putting them on the page, it’s an exercise of some kind of statement. I don’t know that it cleanses it, or makes it feel better. It just makes a petition of it. It declares it. It acknowledges it. It does some kind of craft through writing. It maybe embellishes it for the sake of art, but it puts energy into it. Maybe writing is therapy.

Lynch: What’s the attraction to writing shorter forms like short stories?

Cummings: It occurred to me that we remember by sharp details. When we think about our childhood, there’s sharp details, maybe the color of a coffee cup, or a mustard jar, or the type of table or a pattern.

And those memories are very vivid to you and to your siblings. And you might connect with your siblings returning years later. You both remember that particular detail, or the smell or something about the mood of the room or, or you know, how the air always blew across the yard in an icy way –constantly.

I’m drawn to those highly detailed up-close snapshots of our lives. And the things that we don’t talk about so much. We don’t have time to or we don’t dare talk about them, even though there’s nothing bothersome about them. It’s just an investigation. So, language gives me time to investigate that moment.

Lynch: When did you start writing?

Cummings: I wrote love letters in high school.

I wrote 20 page love letters. I’m not kidding you – every night, in beautiful Jeffersonian cursive. And what did I write? Probably, the worst poetry ever. I mean, probably just saccharin.

That actually was my beginning in writing, but I didn’t apply it in school. It was my sentiment toward her.

Later in college… I actually had been studying art through high school, but in college, I took a poetry class.

Lynch: The love letters: what happened with those?

Cummings: Oh, yeah, she still has some today. Yes. With someone else. It doesn’t make life any less beautiful, though.

Lynch: Do you remember the first story you got published?

Cummings: I do. I was living in Rhode Island in a house on Church Street in Newport, down in the very touristy area. And I got a phone call from the editor of Portland Monthly Magazine in Portland, Maine, Colin Sargent, and I’m talking to him and he’s saying, “Can you give me 750 words?”

And I’m stammering.

He says at one point when I’m really slow to respond. He said, “Well, we’ll just have to forget the whole thing.”

(Laughs) Well, you talk about leaping to life. I just came to life there. And I said, “No, no, no, no, we’ll do whatever you want.”

He did the work. I mean, he was really skilled. He just knew how to cut. He wanted to capture the description of the lighting of a church. And the title of the story is “Electric Church.”

That was my first published story in the Portland Monthly Magazine.

This is probably over 1200 words. This is 1991.

A couple of weekends later, I drove up to his office on a weekend and I saw my name on the cover. It was being displayed as the next coming issue. That was the thunder in my road, you know.

Lynch: Tell me about where you grew up.

Cummings: In Harpers Ferry –right down here where the three states come together. My family grew up down over the hill, near the historic park. Getting close to “The hole,” you know, as this town was originally called. (laughs) “The Hole,” how glamorous.

We lived way down into The Hole, across from John Brown’s Wax Museum, in a little stone house. There were six of us –my parents, my two brothers, my sister.

Tourists were around us all the time. And on one hand, you had the park making, like an open air gallery or an open air mini Williamsburg during the 70s and 80s.

It was just making everything really nicely restored and beautiful. And then on the other hand, you had swarms of tourists and it was almost like a movie set. It was too surreal. Almost.

Lynch: The book is “The Spirit in My Shoes.” John, thank you very much.

Cummings: Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.