This conversation originally aired in the March 3, 2024 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Elliott Stewart has been making zines since he was 13 years old.

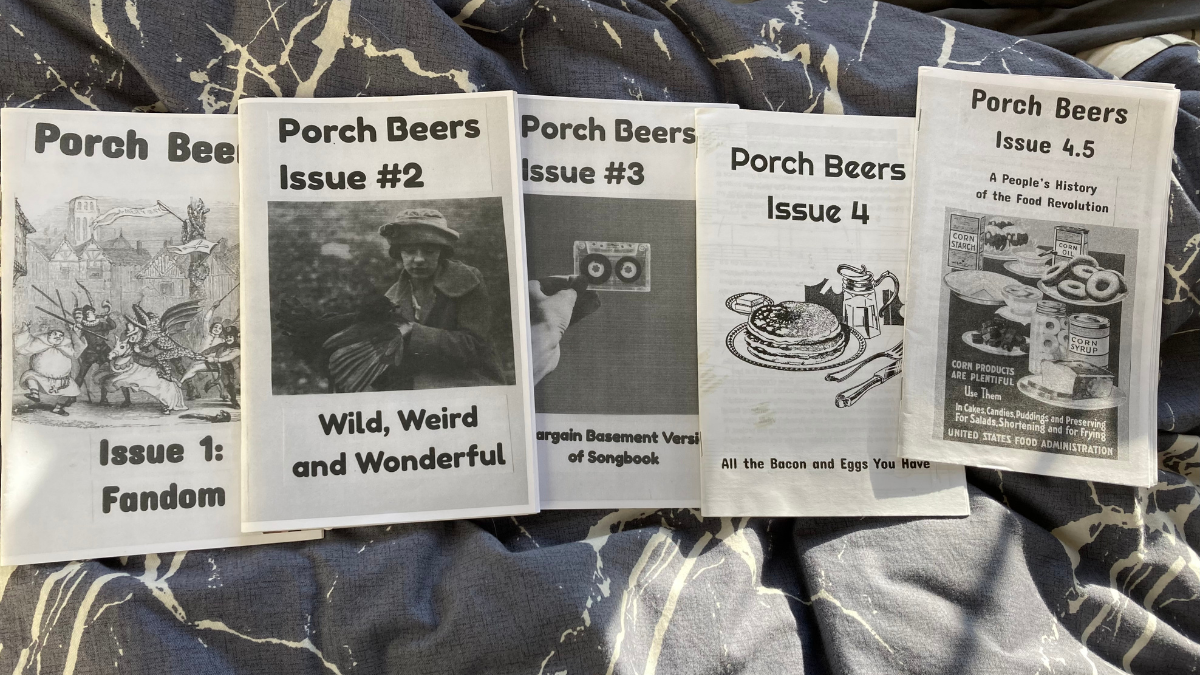

His ongoing zine “Porch Beers” is an incisive look at Appalachian culture, through the eyes of a queer trans man. “Porch Beers” dives into pop culture fandom, West Virginia food and the life of a 20-something navigating moves from Huntington, West Virginia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee and back again.

Inside Appalachia Host Mason Adams contacted Stewart to talk about the newest issues of his zine, and what Appalachia in 2022 looked like through the eyes of a zine writer.

Adams: So I first found “Porch Beers” kind of randomly online using a different search engine than I tried before. I ordered a couple of copies on Etsy and was just blown away. I’ve read zines for a long time, and I’ve read Appalachian zines. These grabbed my attention as a reader.

The writing is fun and short and funny, but also serious and thoughtful. And the stuff you write about is all stuff that I’m interested in. So tell us a little bit about yourself. Who is this person that makes “Porch Beers?”

Stewart: I guess born-and-bred West Virginian, moved around a lot as a kid. We lived with my grandparents, who are ministers and moved out every three to four years to different parts of the state. So I feel like that wanderlust has always kind of been in me. One of my ways getting in and out and recording memories is writing. My grandma has little booklets I made when I was five or six that were maybe my first zines. It’s a good way to be front and center about a lot of intersecting identities that I have. I feel a lot of people come up to me and say that I’m the first person from X group that they’ve ever met. And I don’t know, that’s kind of cool. It has a lot of responsibility to it, but it’s kind of cool.

Adams: Everybody that comes in my house, when they see these zines, they always wonder about the name. Tell us about the name “Porch Beers.”

Stewart: Sure. That was a tradition in Huntington and I’m sure elsewhere where you have a porch. Huntington is a small knit community, to where everybody knows everybody pretty much. You can go by somebody’s house or on their porch, [and they ask,] “Hey, do you want a porch beer?” “Yeah.” So you sit down, you have a talk that could be about nothing. It could be about very important heart-to-heart stuff. But that’s just a hallmark of Huntington summers, and I wanted to reflect that.

Adams: The first issue was about fandom, and you have a few different essays about different arenas of fandom per se. The second issue is about West Virginia and its food. Three was about music. And then you came back to food in issues four and four-and-a-half. What pulled you back to food after you had already written about the different kinds of foods unique to West Virginia?

Stewart: When I go to make an issue of “Porch Beers,” sometimes I will set out and it will be, “I want X theme,” and write around that theme. But more often than not, it’s just, I write a couple of articles as to what I feel, and a theme loosely takes shape. That’s what was happening with this one, to the point where I had a couple of other runner-up themes that I was going with, and my partner was like, “You might as well write about food, because that seems like where this one is drawing you to.” I was like, yeah, he’s right. That was what was on my mind. I don’t know if there was any particular reason for it. But that’s just where the writing led me.

Adams: So I read through these five issues there on specific topics — whether it’s pro wrestling, or the Ben Folds Five or West Virginia Food. But there’s a larger story arc here, too. I mean, I can read growth in these zines. You moved from Huntington to Chattanooga, and back. When you read back the zines, what is the story of “Porch Beers” so far?

Stewart: I do go back and read them at times. It is a little painful to read some of the early stuff, just because I have changed so much as a person. But I’m glad I have a record of it, that these things happened. And honestly, it’s valuable to get stories of growth out there because not a lot of people record the minutiae of life in Appalachia or in the various sub-communities I’m in

Adams: “Porch Beers” tracks this geographic shift, but it also documents a different kind of transition. Can you share a little bit more about that?

Stewart: I am an out transgender man, I have been out in one form or another as trans since about 2018. Just slowly began socially transitioning and then medically transitioning, and considered myself queer as my orientation. It’s been an interesting experience with that, a lot of learning curves. Sometimes people, when they find out, will have … I like to assume that most people are in good faith when they ask questions, but sometimes they can be very awkward or a little hurtful. But I try to take it in stride. Like specific medical questions or things, and if I don’t feel comfortable, I’m at least to the point now, where I’m like, “Hey, that’s kind of a weird thing to be asking me.” A lot of times I’m the first trans person that someone has knowingly met. And that is wild to me.

Find Elliott Stewart on Instagram.