Your browser doesn't support audio playback.

A vista atop Magazine Hill overlooks the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers as they converge at Harpers Ferry. From above, visitors can watch the two bodies of water taper into one, cutting east through the mountains.

Today, the overlook is surrounded by chain-link fences and construction equipment — remnants of an ongoing development project. But just a few years ago, something else stood at the site: one of the most iconic buildings in Harpers Ferry.

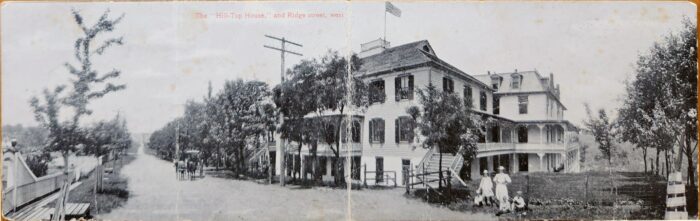

In 1890, a pair of Black newlyweds named Lavinia and Thomas Lovett opened an inn and restaurant there called Hill Top House. Despite the rampant racial discrimination Black Americans faced in the Jim Crow era, they successfully ran the hotel for 35 years, serving a multiracial clientele.

Yet local historian and author Lynn Pechuekonis says many people who visit town do not know the story of the Lovett family, including some of those for whom Hill Top House was once a familiar sight.

That is why she wrote her latest book, Among The Mountains: The Lovetts And Their Hill Top House — to ensure the Lovetts claim their rightful place in the annals of West Virginia history.

Photo Courtesy of the Larry Waters Collection

A Hotspot Of Black History

Harpers Ferry has a long history of achievement in the fight for racial justice and Black civil rights. In 1859, militant John Brown led an abolitionist raid at the town’s armory, hoping to spark a revolt among people enslaved nationwide.

“Many, many refugee Black people came to Harpers Ferry during the Civil War as they self-liberated from their enslavement,” said Pechuekonis, who also chairs the Harpers Ferry-Bolivar Historic Town Foundation. “After the war ended, a lot of them went home or to other places looking for family. But a man named Nathan Brackett headed up the idea that we needed a school for Black people here in Harpers Ferry.”

In 1867, the first college accessible to Black students in West Virginia, known as Storer College, opened in Harpers Ferry. In 1906, it hosted the second official meeting of the Niagara Movement, a civil rights group widely regarded as the precursor to the NAACP.

A few years after the school opened, Thomas Lovett enrolled with his siblings. Lovett came from a free Black family that resided in Winchester, Virginia, a city near West Virginia’s Eastern Panhandle.

While Lovett attended Storer College, its inaugural president, Nathan Cook Brackett, decided to use the school’s dormitories as summer resorts to make extra money, Pechuekonis said.

He hired Lovett’s parents, Sarah and William, to serve as proprietors of Lockwood House, a Civil War-era armory turned college building and then dormitory. Lovett began working alongside them, and made his foray into the hospitality industry.

Lavinia And Thomas

Photo Credit: Negro History Bulletin Vol. 32, Issue 2 (1969).

Meanwhile, Lovett’s time at Storer College came with another formative experience. While out for a hike on the mountainside, he met a woman named Lavinia Holloway. While Lovett soon moved to Rhode Island to work for a few years as a coachman, he maintained correspondence with Lavinia for years.

In 1883, the pair reconnected and married, then moved in together in Harpers Ferry. They lived in an annex of Lockwood House until 1890, when they made the decision to purchase a plot of land on Magazine Hill. With their foot already in the door of the local hospitality industry, they opened a hotel there and named it Hill Top House.

The hotel employed community members and students from Storer College, helping them save up money and gain professional experience over the summers. And, according to Pechuekonis, the business found major success.

“They distinguished themselves as great hosts,” she said. “There was incredible support for this business. It was actually supported financially by white men in the county, and it brought business to other local business owners, both Black and white.”

But the success of Hill Top Hotel was not attributable to Thomas Lovett alone. Lavinia was born into slavery, but soon after was taken in by a white woman in New Hampshire. She grew up in a wealthy, predominantly white environment, which Pechuekonis said gave her more insight into white clientele.

“I think that she really helped boost his natural ability as a host,” she said. “They were great managers. They had a kitchen that was very well known. People came from far and near just to eat at the restaurant.”

While Pechuekonis said it was not unprecedented for Black Americans to run a hotel in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was still a noteworthy achievement. She said that rings especially true because the Lovett family’s business lasted for 35 years, and earned patronage from people across racial backgrounds.

In the Jim Crow era, “people may wonder why white people would come to a Black-owned hotel,” she said. “But it’s because it was good.”

Photo Courtesy of the Corporation of Harpers Ferry Collection

A Story Worth Sharing

Catherine Baldau, executive director of the Harpers Ferry Park Association, first came across the story of the Lovett family in 2016, when she was compiling a historical anthology of Storer College for its 150th anniversary celebration. Baldau’s nonprofit creates “interpretive and educational programs” for visitors to Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, according to the park association website.

“Long story short, I ended up having to come in at the end and write a chapter on the Lovett family,” she said. “I was so intrigued and kept saying, ‘Oh my God, we could write a whole book.’”

Baldau reached out to Pechuekonis with the idea, because she had previously written a biography of the longest-serving Black teacher at Storer College, William Saunders. Pechuekonis agreed, and after a few years of research, editing and writing, Among the Mountains hit the press.

That the Lovetts were able to find such success in the Jim Crow era was remarkable, Baldau said.

“But a lot of that history had never really been told,” she said. “There was a lot of mythology there that we found out was not true. We wanted the real story of it to be told.”

And Baldau said that the book has already found interest among many readers.

“We sold out our first run,” she said. “It’s been very well received.”

Photo Credit: Jack Walker/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

The Hilltop Today

Over the years, Hill Top House hosted several notable figures, including President Woodrow Wilson and his then-fiancee Edith Galt, businessman Vincent Astor and many politicians from Washington, D.C.

While the book spotlights the Lovett family’s accomplishments, it also covers the hardships they endured. In 1912, a structure fire required them to rebuild most of the original building.

Later, after one of their key financiers died, Thomas and Lavinia had to sell their hotel after 35 years in business.

Facing a quick decision, Pechuekonis said they took the best deal they could get. It was enough to repay all the business loans they had taken out, but not enough to pass much wealth on to the next generation.

“I think the saddest thing is that all they got out of it was that their loans were forgiven and they got their personal possessions. These were never wealthy people,” she said. “Somebody made money from the hotel, but it wasn’t the Lovetts.”

The hotel went through different owners throughout the 20th century. But the aged building fell into disrepair at the turn of the 21st century, and was forced to close outright. After years of disuse, the original structure was demolished in 2022.

A Virginia investment group called SWaN & Legend Venture Partners purchased the property with the intention of building a luxury hotel complex on the site, with public access to the Magazine Hill overlook still maintained. But pushback from community members concerned about new development has stalled the project’s completion.

For now, that means Magazine Hill is mostly empty, save a few side buildings still standing today and the chain-link fence foreshadowing construction to come. But Pechuekonis and Baldau hope the new book means the history of the spot, and the family who once called it home, will not be soon forgotten.

Lavinia and Thomas Lovett “were remarkable people,” Pechuekonis said. “So soon after the Civil War, they were extremely successful. They were hardworking, enterprising people who were ambitious to do what it takes to provide excellent service to their clientele.”

“I think that’s really moving,” she said.

To learn more about “Among The Mountains: The Lovetts And Their Hill Top House,” visit the Harpers Ferry Park Association website.

Photo Credit: Jack Walker/West Virginia Public Broadcasting