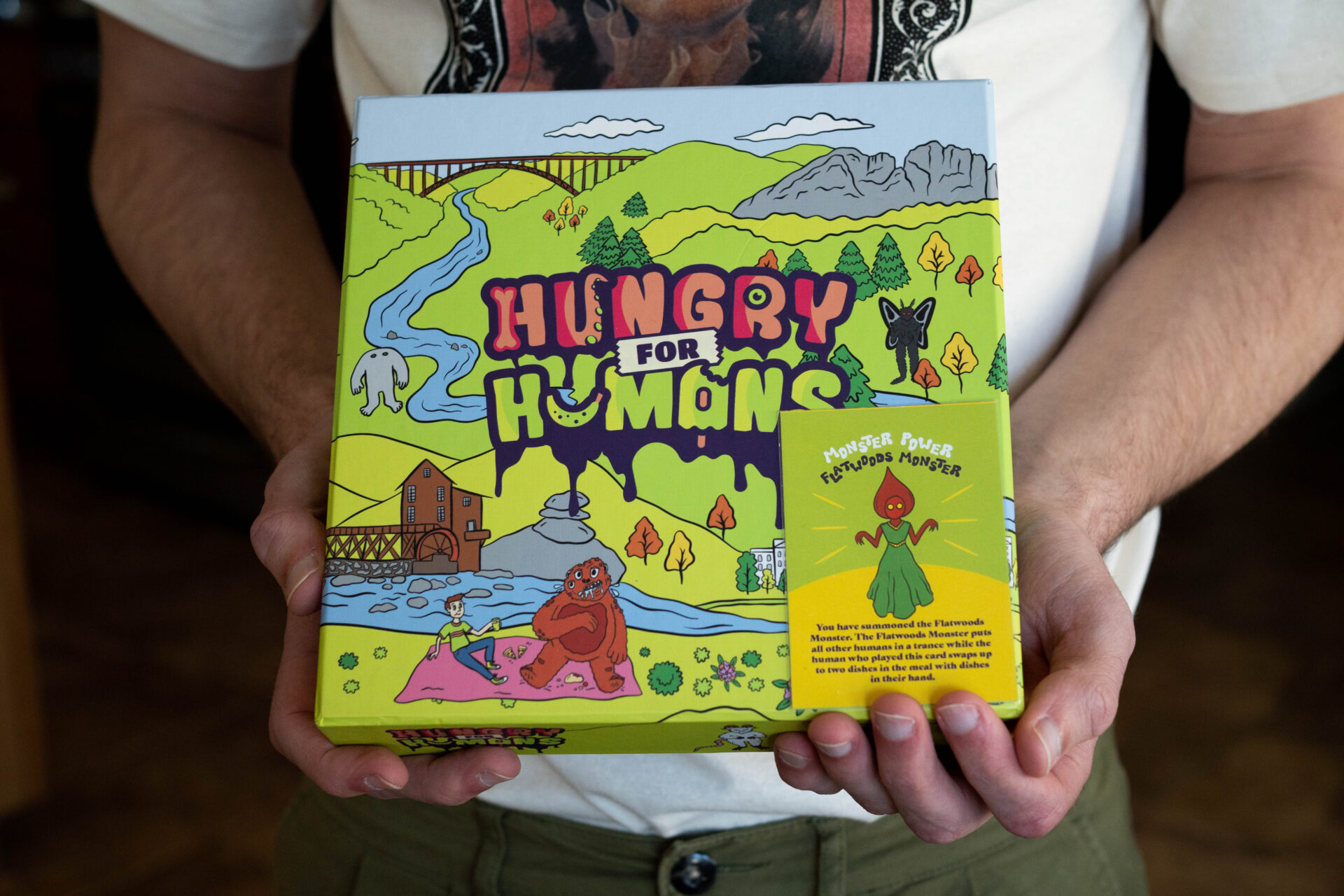

Mothman’s been sighted again in West Virginia. And he’s looking for a meal. He’s part of a new board game that features cryptids and local West Virginia food. Jared Kaplan and Chris Kincaid of Beckley, West Virginia created the game called “Hungry for Humans.”

At Kincaid’s home in Morgantown, we sat around the colorful board arranged in the center of a wooden table. His basement was a board gamer’s paradise – a giant game cupboard lined the wall and the table we were playing on was designed specifically for board games.

It was my first time playing and I was up against the two creators of the game.

“I’m gonna say ‘You look hungry’ and I’m going to make you eat that extra chunky milk,” Kaplan said. “So then you have to go back one.”

The odds were not in my favor.

“So us as the players, we’re the humans, we each have a monster friend who wants to eat humans,” Kaplan explained. “But if you feed it enough, good food, normal food, it’ll satisfy its human hunger and it won’t eat anybody.”

That good food could be a sundae from Ellen’s Ice Cream in Charleston or a burger from the Farmer’s Daughter in Capon Bridge.

“However, if you feed it too much, too fast, it [the monster] becomes too powerful and just explodes,” he continued. “If you feed it the wrong things, because there are some nasty foods in here, then it becomes hangry. And it just gets mad at you and it will eat you. And you’re also out of the game.”

“This is toothpaste with an orange juice chaser,” Kincaid read from a game card. “That’s a minus two.”

Kaplan said they wanted the game to celebrate their home state and its local restaurants.

“I love food. So I just started thinking of a game that involves food,” Kaplan said.

They decided to focus specifically on food from West Virginia restaurants, like Tudor’s Biscuit World and Pies and Pints.

Cryptids are another important part of the game. The Grafton monster, Sheep Squatch, Mothman and the Flatwoods Monster are all special power cards that give you an extra edge on your competitors. In real life, cryptids are rarely spotted. And it’s the same in the game.

“Do you hear that?” Chis asked.

“The buzzing?” I replied.

“No, that’s the sound of the Sheep Squatch coming to scare Jared out of the meal!” he said.

Kincaid and Kaplan met several years ago, in their hometown of Beckley. Kincaid said they bonded over their love for board games.

“We’ve played games with people from very different walks of life,” he said. “From very different places, with very different belief structures, and it’s great, nobody cares about any of it. We’re just there to rob the bank or rescue the princess.”

As a kid, Kincaid learned to play games with his dad and two younger brothers.

“It was always associated in my life with happiness and togetherness,” he said. “We grew up, not super well off, so a board game was about as much entertainment… we weren’t going off to take trips and vacations all the time. We played Uno till we ruined decks.”

Now Kincaid is a family doctor and professor at West Virginia University. He said board games are his escape.

“My career’s pretty taxing, especially lately, as far as time consuming and energy consuming, and it’s just how I recharge my batteries,” he said.

Kincaid has carried on the family tradition of playing games with his own kids. He said they’re budding board gamers with a game shelf that’s starting to rival his.

Kaplan works in marketing at the Resort at Glade Springs in Daniels, West Virginia and he has his own marketing business. He said he was never very good at video games, so he played board games instead.

“For someone like me, who has a ton of anxiety, I actually enjoy being around people more than you would probably think,” Kaplan said. “That’s what I love about board games as it brings people together.”

Kaplan said for him, board games aren’t just something he pulls out at the holidays. He hosts frequent game nights throughout the year.

“It’s really the anchor right now for me that brings my friends together,” he said.

At one of these game nights in Beckley several years ago, none of their other friends showed up, so it was just Kaplan and Kincaid. Instead of playing something, they started brainstorming game ideas.

That was the start of “Lonely Hero Games,” their board game company. After diving deeper into the world of board games, they quickly learned that a good game needs good artwork.

“If your art and your game is not good, you’re going to hear about it,” Kaplan said.

Morgantown artist Liz Pavlovic was the perfect fit for their second game, Hungry for Humans. She’d never illustrated a board game before, but she’s known around the state for her funky renditions of West Virginia food, like pepperoni rolls, and cryptids like Mothman.

“I just really like celebrating the weird stuff in the state and the stuff that maybe people don’t know about, especially if you’re not from here,” Pavlovic said.

It was Pavlovic’s first time playing the game, like me. Her monster friend was none other than the fictional Flerbin Gusselpot, a peculiar creature, loosely inspired by a bat. It’s her personal favorite and just one of the many monsters she illustrated for the game.

“He has a really weird nose. And otherwise, sort of a reptile body with a horse tail. And some fangs and like a really long tongue and really long fingers. He’s purple with spots, orange spots,” she said.

When Hungry for Humans launched on Kickstarter last fall, Kaplan and Kincaid received an unexpected amount of support for the game, specifically from West Virginians.

“I reflect on that and feel extremely lucky to be from West Virginia and have our community,” Kaplan said. “If you’re creating a game in somewhere like New York, everywhere you look, people are doing that. In West Virginia, though, people take a lot of pride in people who are doing things that are different and unique, and they want to support each other and lift each other up.”

Kincaid said he enjoys playing Hungry for Humans, but he rarely wins. And indeed, Kincaid’s monster – Porgis Bean-hammer – was the first one to explode.

“Don’t blow me up! Blow him up!” Kincaid pleaded.

That left me, Kaplan and Pavlovic. When we totaled up the meal, it was a seven – meaning that all of our monsters were about to explode. I had to think quick. Without hesitating, I played a “Yuck” card – landing me right at the finish.

They may have let me win, but I’d like to think otherwise.

Hungry for Humans will be available this summer. And even though their game isn’t even on the shelves yet, Kaplan said he already has at least 15 new game ideas.

“There’s a skeleton of a game under this table right now that I’ve been working on,” Kincaid said.

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, which is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to Inside Appalachia to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts, and culture.