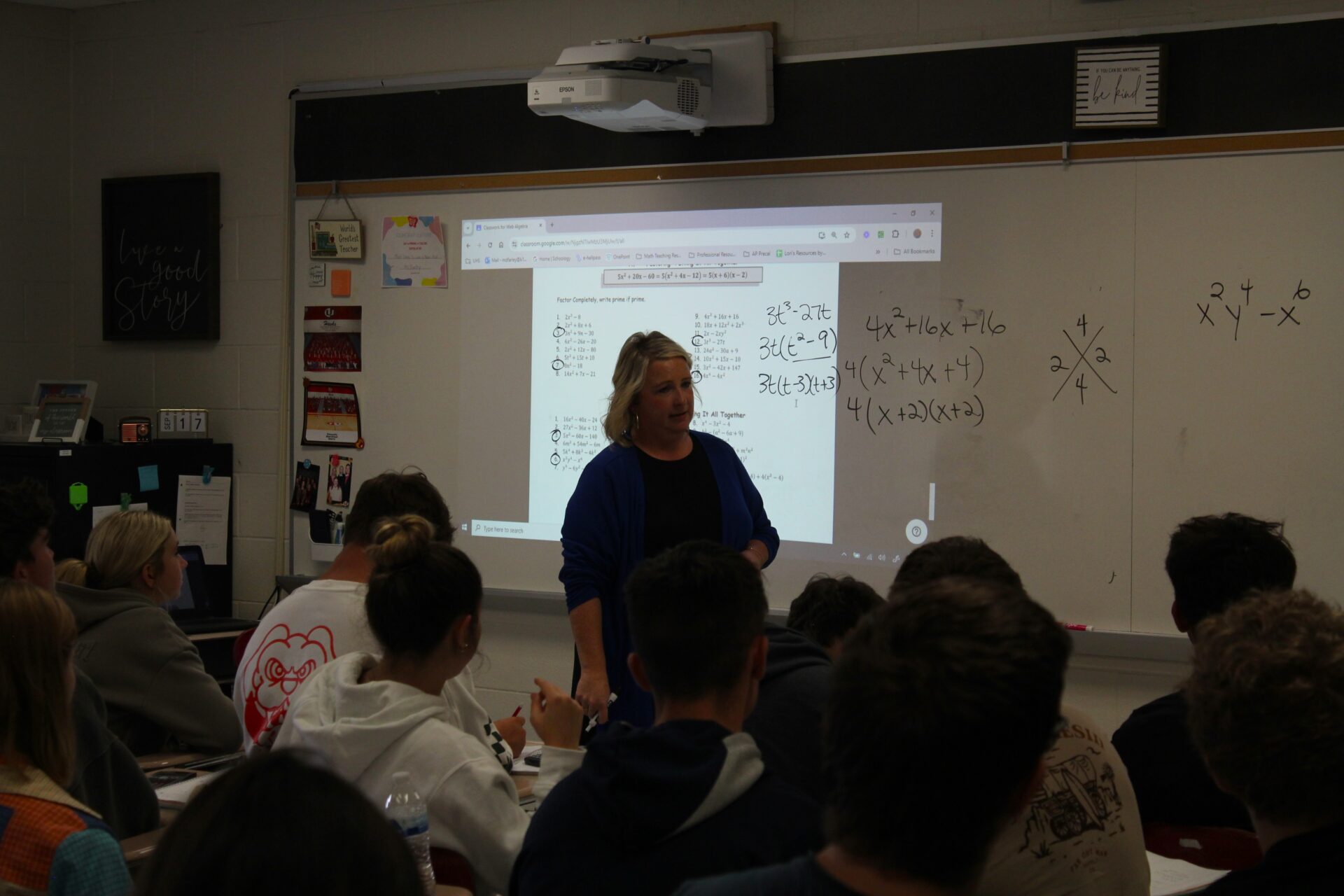

On a recent Tuesday morning, Melissa Farley’s math class was hard at work on polynomial factoring. There were notebooks and pencils, a projector displayed formulas on the board and Chromebooks were open to calculators. But one device not seen in Farley’s class or any other classroom at University High School (UHS) in Morgantown this year are cell phones.

Smartphones are often presented as modern tools that offer us the world’s knowledge at our fingertips. But the past several years have proven they can also be a serious distraction to all age groups.

Schools across West Virginia are starting to restrict access to smartphones in the hopes of directing students’ attention back to the front of the classroom.

“Let’s face it, no matter what I do in a classroom, how engaging I try and make it, if your girlfriend or your boyfriend or your best friend or even your parents are texting you about something, I’m not as exciting as that, and the math I’m talking about is not as exciting as that,” Farley said.

Monongalia County Schools is one of three school districts in West Virginia that has implemented some form of smartphone restriction for the 2024-25 school year. Farley said just one month into the year, the change is obvious.

“We just had our first assessment the other day, and my grades were through the roof in comparison to what they’ve been in the past,” she said.

Farley said she tries to limit the homework she hands out and gives her students time in class after instruction to work and ask her questions. Last year, she said students wouldn’t ask for help, leading her to believe they were grasping the subject. But since the phone restriction, the questions haven’t stopped.

“I never have a free second, there’s always someone asking for help,” Farley said. “It’s just made me realize before they really weren’t working on it, even though I maybe thought they were, they weren’t. They were distracted by their phones and by texting or social media or looking at a TikTok video. I really have seen it academically that they are using their time in class very wisely, which should make their life at home better. It should give them more free time, because they can get their stuff done at school.”

UHS senior Daniel Grabo says he has noticed a difference in himself.

“I wouldn’t really say it’s a punishment, but rather something to keep me focused,” he said. “And it’s honestly worked. I’ve definitely been more focused throughout the last few weeks than I was, I think, all year last year.”

Across the country, close to a dozen states have either implemented or considered implementing legislation to restrict phone usage in schools.

More broadly, almost one in four countries is introducing bans on smartphone use in schools from Côte d’Ivoire to Colombia, from Italy to the Netherlands. That’s according to the 2023 Global Education Monitoring Report from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The UNESCO report advised that technology should only be used in class when it supports learning outcomes, but points out the potential for distraction, as well as the particular risk smartphones pose to childrens’ privacy and mental health.

Monongalia’s practice is one of the strictest, requiring students to lock their phones into Yondr bags, which can only be opened magnetically at the school’s exits at the end of the day.

Ashley Wankey, another UHS senior, sees the total lack of access as a benefit, because the choice is out of her hands.

“I’ll be doing work, and then I’d be like, ‘It’s just too much work. I just want to stop.’ And I’ll reach for my phone, and I have to realize, now I have to finish this before my due dates,” she said. “So it was a little harming knowing that I had my phone accessible all the time. Now that I don’t, I can actually focus and not be distracted.”

Chris Schulz/West Virgina Public Broadcasting

Eddie Campbell, Monongalia County Schools superintendent, said having no access ultimately takes all the pressure off the student. He said beyond classroom engagement, social pressure was actually another factor the county considered when restricting smartphone access.

“We obviously can’t do much about what happens outside of school hours, but we felt very strongly that in order for us to regain some of our ability to help students develop positive relationships with their peers in school, we needed to eliminate some of those negative components of having cell phones, the internet, social media, available during the school day,” Campbell said.

A meta analysis of cell phone restrictions in schools published in the Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy found that student phone use has been associated

with increases in cyberbullying, academic dishonesty, sexting, and poorer mental health. Moreover, the study concludes that “consistency, and follow-through, in expectations is of fundamental importance if students are to respect rules limiting their freedom if students are unlikely to abide by rules that are not consistently enforced.”

Administrators in all three counties said creating a uniform policy was key to reduce friction, and different counties have taken less restrictive approaches. In Ohio County, students place their phones in a container by the door during class, but are otherwise free to access them between classes and during free time.

Meredith Dailer, principal at Wheeling Park High School, said the social positives of restricting phone access at school is already visible at her school.

“Even in the lunchroom, we see the cell phones being put away, even though they have access to them, we see the cell phones being put away,” Dailer said. “I think it’s building that human connection that is lost so often with technology, and it’s really positive.”

She said one of the only pieces of negative feedback the county received from parents was their students not having their phones during an emergency, part of the reason they ultimately allowed students to have phones between classes.

“We felt like this was really striking a balance between having cell phone free instruction in the classroom, but also having access to their phones in an emergency,” Dailer said.

Campbell said Monongalia County schools are well equipped to address security issues without students accessing their phones, something first responders have said can actually create more confusion in an emergency situation.

“We want students following and listening to directions. We don’t want them being distracted by being on a cell phone,” he said. “These are all safety procedures that we practice and we talk about when we do drills in schools. Prior to the Yondr bag, we didn’t say to kids, ‘It’s okay to get on your cell phone and communicate with your parents.’ Even though it’s a drill, we practice it like we want to do it in real time.”

Berkeley County Schools is the third district to implement a phone restriction this year. Students can only use their phones before or after school and at lunch. Ronald Branch, assistant superintendent of pupil services, says small things like monitoring students so that phones aren’t used between classes or the use of secondary devices like smart watches has posed minor challenges, but his county will review the policy as the year progresses.

“It has teachers, service personnel, parents, other members of our community on that. So we’ll get a variety of perspectives on that, and then look to make changes, if any are necessary as we enter next school year.”

Interest in restricting cell phone access at schools is growing in West Virginia. The topic has come up at more than one state Board of Education meeting this year, and while Gov. Jim Justice expressed support over the summer, he said the decision should remain at the local level.