This story originally aired in the Feb. 17, 2023 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Sometime in the 1970s, a group of model railroad enthusiasts in Charleston, West Virginia started getting together at the local Presbyterian Church to talk trains. As the club grew, they found a bigger space where they could set up little dioramas for their engines and cars to traverse.

Then, in 1998, the Kanawha Valley Railroad Association got a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The county commission gave them some money to build a brick-and-mortar clubhouse. Members decided to use the new space to build one big, permanent model train layout.

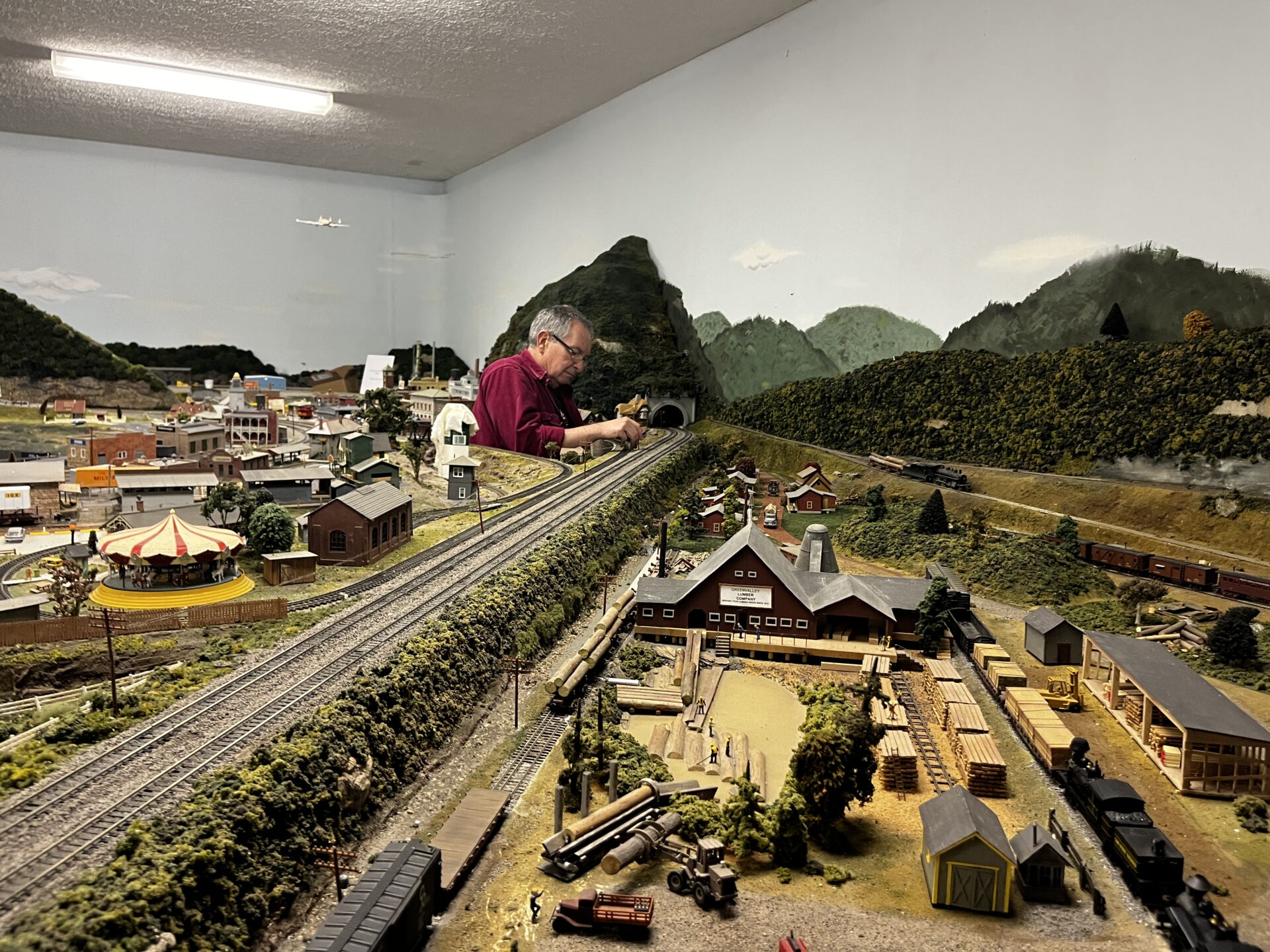

So, like the steel driving men who once tamed the West Virginia mountainsides, they set to work. They built huge tables where they laid track and wired it up to electricity. They crafted rock outcroppings from stacks of ceiling tiles that they roughed up with wire brushes — though sometimes they’d just find a nice looking rock outside and add it to the layout. They built houses and businesses and barns, coal tipples and a replica of the Hawk’s Nest Dam. They made thousands of trees from white poly fiber stuffing that they dipped in watered-down school glue and rolled around in ground-up green foam.

Completing the layout took thousands of hours over about five years. But in the end, the club filled in the space, wall-to-wall, with the communities of Charleston, Elkview and Thurmond all at one-87ths scale.

And you can see it — just stop by the Kanawha Valley Railroad Association’s headquarters in Charleston’s Coonskin Park, any Sunday from 1 to 4 p.m. Admission is free, though donations are appreciated.

“It’s not only for us to enjoy but it’s for the community to enjoy,” member Anthony Parrish said. “Not everybody can have one of these in their basement.”

Club members have created a little game for visitors to help them fully experience the layout in all its detailed complexity.

“We have a ‘see if you can find it’ sheet that we give our visitors,” said Parrish, who helped build the layout. “There’s one scene here where there’s an old moonshine still located in the forest, in an area you wouldn’t think to look for a moonshine still. There’s rock climbers and stuff [and] a barber shop.”

Look really closely, and you start to notice something besides those Easter eggs. Is that a ‘57 Chevy crossing the Southside Bridge in Charleston? There’s the Kanawha County Courthouse on the boulevard — but where are the high rise office buildings or Haddad Riverfront Park?

This model doesn’t only capture the landscape of southern West Virginia. It captures a moment in time: a single sunny summer afternoon in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The club’s old-timers did the majority of the work on the model, and this was a way of remembering and reliving a bit of their youth.

But that doesn’t mean the club is stuck in the past. As you stand there, marveling at the West Virginia of yesteryear — along comes a Northfolk Southern diesel locomotive, just like the ones you might see chugging down the tracks today. It belongs to Austin West. At 15, he’s one of the group’s youngest members.

“The engines I have are ones that’s actually been in my backyard that I’ve seen,” West said. “I was like ‘I want to have that.’ And now I can.”

West doesn’t have a layout at home, so the model at the clubhouse gives him somewhere to run his trains. The club also has train cars and digital controllers that members can borrow, greatly reducing the barrier of entry for what can be a pretty expensive hobby.

But that’s not the only benefit newcomers like West get from their membership dues. He’s learned a lot from the more experienced members. Once you really get into it, it’s not enough to collect locomotives and railcars — you’ve got to modify them.

“The cars are mostly dirty and patched. And the front engine is supposed to look like it caught on fire, like the real thing,” West said.

While West prefers modern trains, his buddy Joesph Watson is focused on the Norfolk and Western railroad — trains that disappeared 20 years before he was born. He has diesel and steam locomotives from the N&W line, which he’s weathered with paint and special chalks using techniques he’s learned from other members.

“It’s all about making it look real,” Watson said. “Everybody here does it different. Get those different opinions and add it into what you do, and it makes your own style on how you model.”

It has enabled Watson to recreate something he never saw in real life. He’s 20 and the N&W went away in 1982, when it merged with Southern Railways to become Northfolk Southern.

“It makes you look back on, how would these be back in the day?” he said. “What would it be like to stand on the side of a railroad in the 1930s and see these coming down the tracks?”

And there are his trains, clacking right past Austin’s modern Northfolk Southern locomotives, in this snapshot of midcentury West Virginia. The past and present of American rail transit, alive on a small scale.

The future, though, is less certain.

Yeager International Airport sits just up the hill from Charleston’s Coonskin Park. And a proposed multi-million dollar expansion of the runway there would require a whole section of park to be filled in with dirt — right where the clubhouse sits.

The building isn’t doomed just yet. The Federal Aviation Administration is still studying the project. But the train club has already started looking for new potential locations.

Member Mike Reynolds said any move will mean the end of their gigantic model of southern West Virginia rail lines.

“This was built to be permanent, so it would be really hard to break it up,” Reynolds said. “And whatever we take will be partially destroyed in the process and have to be redone. But we don’t know where we’re going to, so we don’t know how much room we’ll have. If any.”

It’s a little ironic. The very mode of transportation that supplanted trains as Americans’ go-to mode of cross-country travel now threatens to take away a place where that history is celebrated.

But while club members are concerned about the future of their building and layout, no one seems too worried about the future of the club. New train fanatics are being born every day.

“I’ve got a grandson that’s 3 years old. And from the day he had any idea what was going on, he has wanted to fool with trains,” Reynolds said. “It’s almost like a fox knows how to hunt. They already know what trains are all about.”

“I think it’s magic,” he said. “I do. I think it’s magic.”

The Kanawha Valley Railroad Association will also host its 17th annual Model Train and Craft Show at the Charleston Coliseum and Convention Center on March 11 and 12. You can find more about it on their Facebook page.

——

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia and the Folklife Program of the West Virginia Humanities Council.

The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts, and culture.