Automakers are investing in new electric vehicle factories and production lines in factories around the Southeast, even as the United Auto Workers, under the leadership of its president, Shawn Fain, is pushing to unionize those southern factories.

Tennessee reporter Katie Myers has been covering the story of how automakers are getting into EVs — and about how organized labor is trying to get into the South.

Inside Appalachia host Mason Adams reached out to learn more.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Adams: So, we’re talking because of this buildout of electric vehicle factories across the southeast. A number of companies are leveraging federal funding to invest in new plants in Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. It’s even been called the “battery belt.” What’s going on here?

Myers: The Inflation Reduction Act made nearly $100 billion available for the domestic electric vehicle supply chain. $15 billion of that is to help existing factories transition. It’s a huge pot of money that private companies are obviously really excited about. Meanwhile, the auto industry has been trending towards the Southeast, away from its traditional home in the Midwest. A lot of this has to do with the generally lower wages, labor protections and environmental regulations that can be found in many states in the Southeast, due to political forces there. Particularly, foreign automakers have been moving towards the U.S. Southeast, which is kind of funny. It’s almost like countries like Germany with strong unions [are] outsourcing cheaper labor to us, and a lot of those are electric vehicle manufacturers.

Adams: All these new factories and investment in manufacturing comes at a time when the United Auto Workers is making a big push. First, last year, the UAW launched a strike against the big three, Ford, General Motors and Stellantis. And now there’s been a push to unionize factories in Appalachia and the South, in states that haven’t traditionally been friendly to organized labor. How is that labor push going?

Myers: First off, I think it’s important to say the UAW strike was a mark of a change in strategy and direction. If you talk to people who were higher up in the union, or who were longtime workers, there was sort of a frustration for a long time around a perceived stagnancy in the union strategy — knowing that the auto industry was trickling out of the Midwest towards the Southeast, and struggles with democracy within the union, decisions that weren’t being made with the consent consultation of workers that belong to the union.

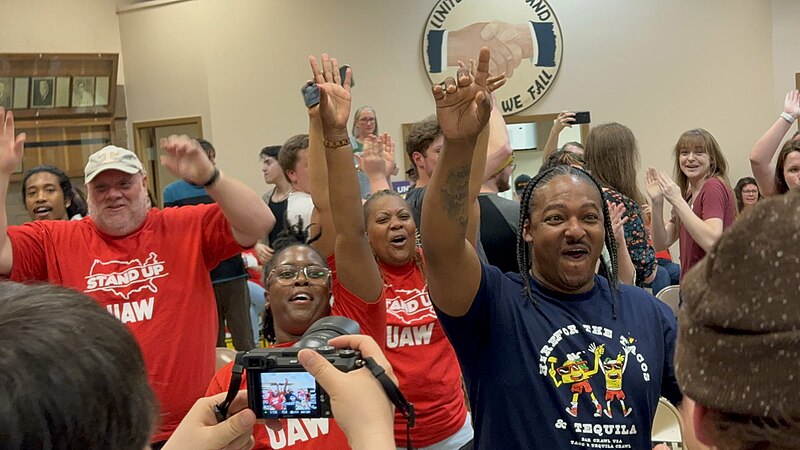

Shawn Fain, for a lot of folks, represented a change in strategy — real attentiveness towards trying to think about the electric vehicle transition, thinking about where geographically the union needed to grow. This win is a huge morale boost, and that does a lot for organizing. Workers see you’re winning, and they’re like, ‘Oh, my personal risk that I’m taking in joining this union or in going on strike is less now because more people are with me. This union has won and can win.’ That’s all to say that the UAW really struggled to organize in the South for a long time. Starting with a big loss at a Nissan plant in Smyrna, Tennessee, which was the big first foothold of the auto industry in the South. Now that Volkswagen has been located in Chattanooga for a while, they tried to organize Volkswagen a couple of times, [and] lost every time up until this year because there were strong anti-union campaigns. There was a strong collaborative effort by legislators in Tennessee to trash talk the campaigns [and] crush them. Workers were scared. Many of them didn’t have union families, people that the union paid for their dad’s pension or whatever. In the South, there’s not that same kind of legacy unionism [that there is in the Midwest]. So, it can be hard to convince workers it’s worth it. But this time, after two tries, the UAW won their campaign in Chattanooga, and that was a huge deal. It’s the first foreign automaker, certainly the first foreign automaker in the Southeast, and it’s an EV parts manufacturer. So, it hits a lot of points that are really big in the future of the UAW and the future of electric vehicles. It’s a long game that Shawn Fain is playing here, because it’s not easy to organize in the South, and they lost an election after that. They lost the Mercedes-Benz election in Vance, Alabama, because those same tactics were employed. That hasn’t really slowed the UAW down. Shawn Fain said, “We know this takes a few tries, we’re going to come back.” And they actually won another. They won in Spring Hill, Tennessee, which is once again EVs. Organizing the South and organizing the EV [plants] are the future of the United Auto Workers. The Biden administration is pushing EVs to be two-thirds of U.S. car sales by 2050. Knowing that industry is moving to the South in this way, if UAW wants to survive and continue to have bargaining power in the auto industry, this is where they have to be.

Adams: I understand the Spring Hill unionization was done with the assent of General Motors and LG, the battery company there. Are companies starting to come around on that? Or is that wishful thinking?

Myers: I think it’s never about companies suddenly opening their hearts. I think that once they understand that the union is a powerful enough force that they have to reckon with it, they can’t just ignore it and do a few anti-union videos for their workers and expect things to be easy. Then, then they know that they have to deal with the reality of that.

Adams: Even after the vote at the Alabama plant failed, UAW has continued to try to organize and has success in Spring Hill. What’s the outlook on the broader future for this push?

Myers: It seems like UAW is not going to stop. Every time Shawn Fain gets in front of the mic, he’s like, “We’re organizing the South. We’re going back to Alabama. We’re going back to Tennessee. We’re going to Georgia.” That is clearly their strategy. They’re going to keep pushing and putting energy and resources into organizers in the South, which historically, not all unions have been great at. They sort of give up the South and say, “Well, you can’t win there, it’s not worth putting your resources into.” And so this is a big turn that I wonder if other unions will see and emulate. I think that they’re just recognizing that this is a fight for what’s called “just transition” that we in Appalachia know a lot about, but under a different industry. It’s this recognition that energy transition is happening legislatively and politically. It’s happening all over the world. It might be happening more slowly than climate scientists would want. Without workers involved in it, it just becomes more of the same extractive relationships to land and people, more dangerous jobs. It also becomes a PR problem for climate advocates, because when workers in fossil fuel industries have high-paying jobs that were hard won with — in some cases — the literal blood of workers. and then all of a sudden, they’re asked to go transition into renewable energy, EVs, whatever: “Sorry, the jobs are kind of contract-y and not very well protected, and like a lithium battery might blow up on you.” You can see why workers wouldn’t be enthused about that. I think UAW and other building trades unions are setting precedents that [are] a really important part of the energy transition question. Obviously it will not happen without people doing the work to make it happen. The unions themselves are setting precedents that they’ll benefit from in the future, because they will continue to have membership. There’s also a philosophical question of, “What are we really doing here? What kind of world are we building?” Climate solutions where decarbonization is reinforcing existing inequalities, causing new pollution problems with less of a safety net for workers. [You ask,] “What is it for? What is it all for?”

Katie Myers covers climate stories for Blue Ridge Public Radio and the online magazine Grist.