The West Virginia mine wars played an important part in U.S. history, but for decades were often left out of history classes.

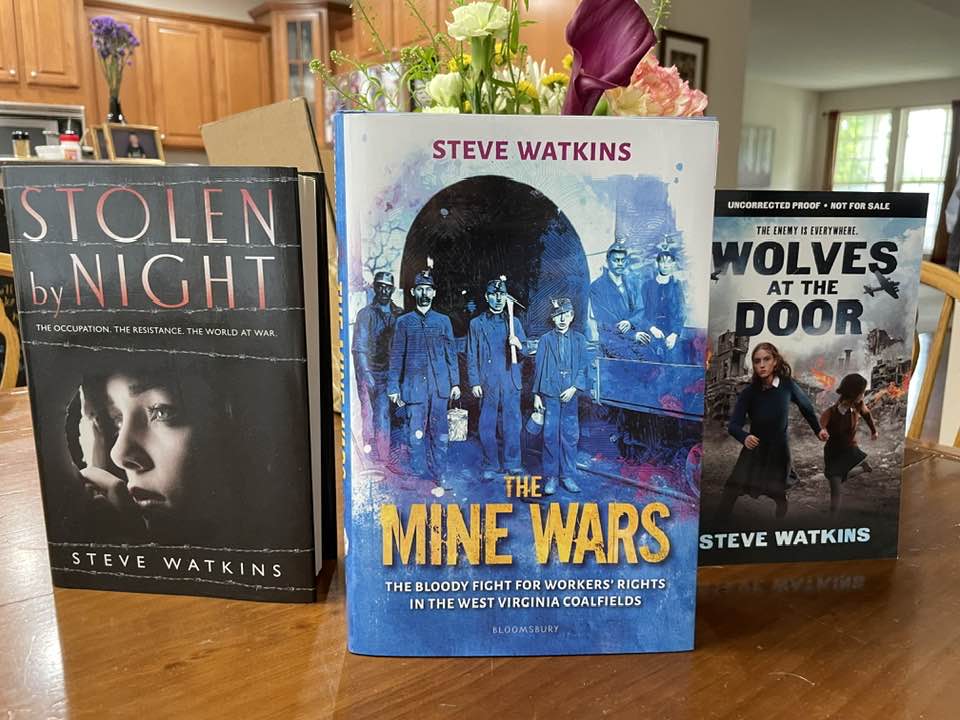

A new book aims to change that. It’s titled The Mine Wars: The Bloody Fight for Workers’ Rights in the West Virginia Coalfields, by Steve Watkins.

The mine wars occurred in the early 1900s as the United Mine Workers tried to unionize coal mines, and coal companies fought back — literally. The conflict culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain, which was the largest armed insurrection in the US since the American Civil War.

After running across the new book in the library, Inside Appalachia host Mason Adams spoke with Watkins to learn more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Adams: A lot of listeners will know about the mine wars, but for folks who may not be familiar, can you give a thumbnail of what the mine wars were?

Watkins: The mine wars, plural, really began in the 1910s with the Paint Creek Cabin Creek war — basically miners fighting for the right to unionize after years, decades of brutal repression, brutal in the extreme, I should point out… beatings, murders, disappearances, lost jobs, strikes in which children suffered malnutrition, [and] many died from opportunistic disease. It was a pretty successful strike, but it took over a year for the miners to win the right to unionize. In southern West Virginia, the owners still held strong sway. The owners brutally repressed any attempts to unionize. You tried to unionize, you get blackballed. They forced people to sign “yellow dog” contracts, which, if you so much as looked at a union organizer, you could lose your job. What that meant down there was you didn’t have a job, you had nowhere you could go and work in the mines, when there are few jobs and few opportunities. You’re working in isolation in these coal mines, that’s pretty devastating stuff.

Adams: How did you first learn about the West Virginia mine wars?

Watkins: My original introduction was the movie Matewan back in the ‘80s. I remember when that came out and just being blown away, thinking naively, stupidly, that this is going to wake people up. I don’t think that movie made a million dollars total. You know, there weren’t a lot of viewers, even though the great James Earl Jones starred in it as a fictional character, Dan “Few Clothes” Chain. His character was actually transported from the earlier mine wars at Paint Creek, Cabin Creek. He was a figure who was very important then, part of the so-called “dirty eleven,” sort of a guerilla organization that did the dirty work for the miners’ union. They transported him to the Matewan Massacre and the Battle of Blair Mountain for that movie [although] he wasn’t really active during that. And a lot of people don’t know this, but James Earl Jones, when they began funding for the Mine Wars Museum in the town of Matewan, he was one of the very first donors. He has said that Matewan was the favorite movie he ever made.

My publisher wanted me to do a deep dive into this and find a way to tell the story that made it accessible for younger readers. The story of the mine wars and the Matewan Massacre and the Battle of Blair Mountain was deliberately buried in West Virginia for decades. You talk to older people there, and they grew up going to school, never hearing a word about the United Mine Workers of America, about the Battle of Blair Mountain, about any of this. It was just buried in West Virginia history because, literally, the mine owners wrote the textbooks that they used. It really wasn’t until a generation ago that people started reclaiming this history. It’s a very gripping narrative of courageous and not always the most polite of people standing up for their rights. I think it’s the most deeply American story and the most deeply inspiring American story, frankly, that we have.

Adams: When you are researching and writing about the mine wars, what did you learn that surprised or really struck you?

Watkins: The coal mine owners and operators, especially in southern West Virginia, wanted to make sure that they did not have employees or their families that would cause them any trouble. They wanted a docile population of workers that they could control. They owned the houses. The stores they paid in script, not in cash. They basically worked in these isolated places where people had few options. This mixture was an idea by a mine operator and owner named Justice Collins. Justice Collins’ idea was this: hire a third West Virginia mountain folks, white people; hire a third Blacks from the deeper south, many of them former slaves or the descendants of slaves; hire a third from Eastern Europe, where there was a lot of coal mining, and recruit a lot of people from Slavic nations, from Southern Italy and so forth. Populate your coal towns or your coal camps with these segregated sections of Eastern Europeans who didn’t speak the language of the others, Blacks and whites. The assumption was, they would work underground, but they wouldn’t organize together. That was his idea, and he sold it to the mine owners’ organizations. This caught on, and so mines all over embraced this practice, and it totally backfired on them. Because, for one thing, when you’re underground, you’re covered with coal dust. Everybody looks the same. But also, the common cause these people had, the things that united them, was so much greater than the things that might have divided them. They came together in the United Mine Workers of America, which was the first of the unions that said we will not discriminate on the basis of anything. You had African Americans, white hillbilly Americans, Eastern Europeans, coming together, not divided in the ways that certain politicians are trying to divide us today. They were coming together for common cause, to support their families, to stand up for their rights as workers, their rights as Americans, for free association, freedom of speech. They combined to unionize. I mentioned Dan “Few Clothes” Chain earlier. The three leaders of the dirty eleven were Dan Chain, who’s African American, a guy named Rocco Spinelli, who’s from Italy, and a guy with the greatest name ever, Newt Gump, who was just a hillbilly West Virginian. The three of these guys, they went to federal prison together. They organized together. They literally fought together, and they fought for one another. To me, you know, that is as American a story as there is, people coming together to stand up for their rights. And these people were proud of themselves as Americans, not as some dissident faction. They saw themselves as proud Americans and proud West Virginians.

Adams: How have people responded to your book? What are you hearing from them, and especially from young people?

Watkins: What I’m hearing directly has actually been from the parents of kids who are picking up the book going, “You know, I had heard these stories. I hadn’t read them pulled together in this sustained narrative.” What I’m hearing is that people are drawn into the narrative just because it’s a hell of a story. The characters in this story and the drama, frankly, are just gripping. It’s kind of unbelievable. Things happen — a lot of pretty intense violence, assassinations, and they sent biplanes to bomb the miners, for God’s sake. People are recognizing the need to recognize and celebrate what I had hoped that they would, which are the contributions of these these union leaders who literally put their lives on the line and lost their lives in many cases.

Adams: Why should young adults or people generally learn about the West Virginia mine wars?

Watkins: I think America has turned its back on labor. The labor movement has always been fighting uphill. In a way, the Battle of Blair Mountain is a metaphor. These guys are literally fighting their way up a mountain, seeking justice, seeking to roll back martial law that had been declared. Many of their companions over there in Mingo County were arrested just for talking to a member of the mine union, just for having a copy of a mine union newspaper. That’s it. I think we take the labor movement and those who have labored [for granted] at our own peril. I don’t think we want corporate America running the show here, even though they kind of are. The labor movement is still very active today. You look at what labor unions have done for us in terms of ensuring fair wage, safe working conditions, all of the progress that we’ve made in terms of protecting young people in the workplace. That didn’t come because of the largess of owners; that came because of activism from the bottom up, reclaiming your past, your history, your story, and taking pride in it. I think too often we’re an economy that kind of divorces ourselves from people that pick up a shovel and get down there in the mines and put their lives on the line to make a living, but also to serve the country. We do ourselves a disservice by taking all that for granted. This is a story, one of many, that helps reclaim that history and tell that story, I think.

The Mine Wars: The Bloody Fight for Workers’ Rights in the West Virginia Coalfields is now available from Bloomsbury Children’s Books.