Out of disaster, sometimes comes a song. In 2016, torrential rains resulted in one of the deadliest floods in West Virginia, destroying homes in White Sulphur Springs. The event and its aftermath inspired musician Chris Haddox to write “O’ This River.” Now the song has new purpose. Haddox recently used it to raise money for people in North Carolina after Hurricane Helene.

Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporter Connie Bailey Kitts spoke with Haddox about the story behind the song.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Connie Kitts: Chris, could you introduce yourself?

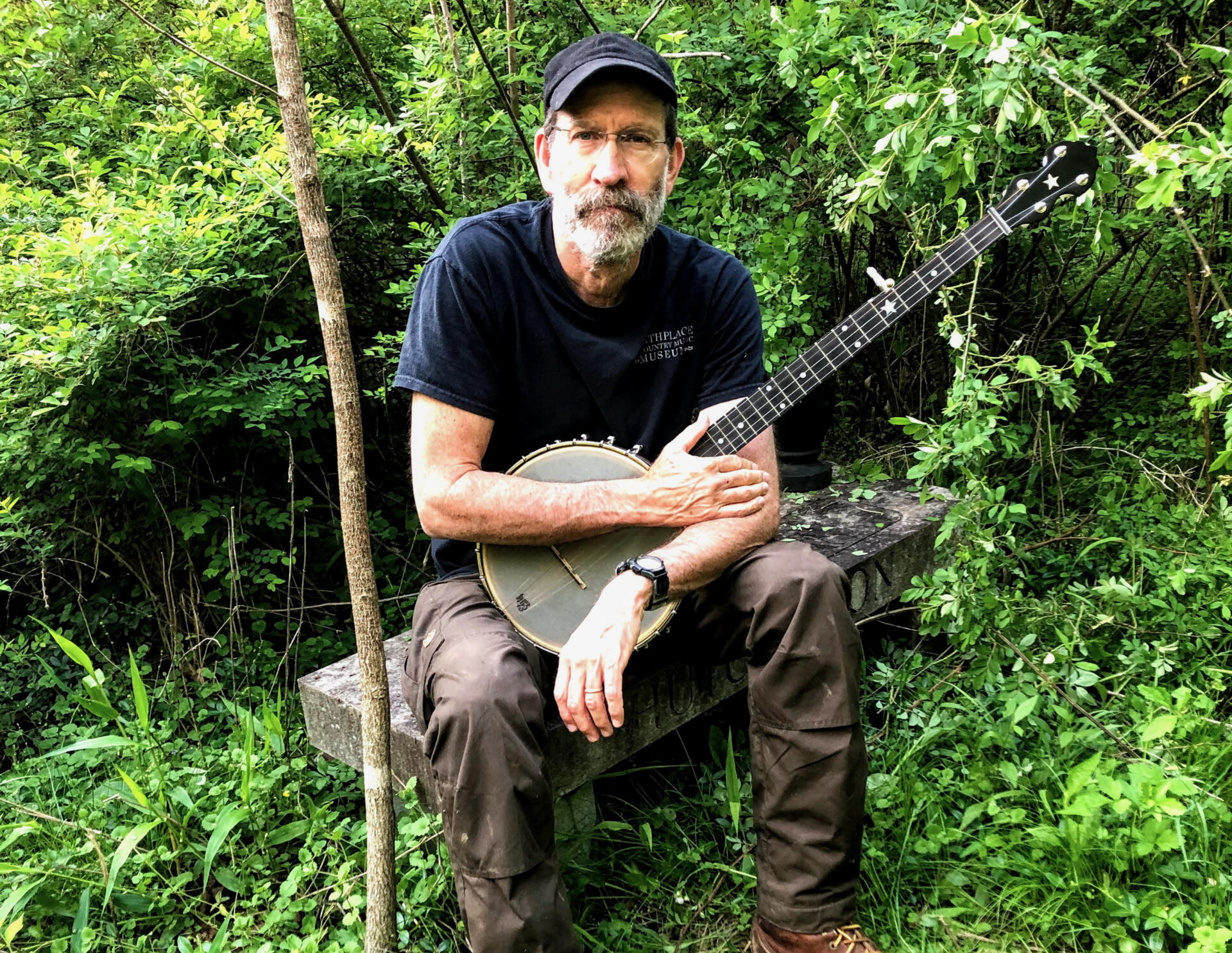

Chris Haddox: My name is Chris Haddox, and I live in Morgantown, West Virginia. I’m a professor at West Virginia University in the College of Creative Arts and Media and the School of Art and Design. I earn my living through my “professorly” work, but music’s been the constant in my life since I was a kid.

Kitts: Your song “O’ This River” came out of the 2016 flood that hit White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. Can you tell us what happened and about your connection to that event?

Haddox: I attend the Presbyterian Church here in Morgantown, and I got a call – somebody at the presbytery office in Charleston. They were looking for musicians to go to White Sulphur Springs. They said, “You know, there’s a lot of people there cleaning up and providing food. Would you be interested in going to just play music? Then maybe that’ll take people’s minds off things for a while.”

There was a big tent that was a central staging area for meals and communications and that sort of thing, and we sat under there and played, and people seemed to enjoy it.

One of the times I was sitting under the big tent, there was a woman sitting there by herself, kind of staring off. And I thought, well, I’m going to go over – she looks distraught, and I’m just going to go sit beside her and chat with her if she wants to chat.

She just started talking, and not really talking directly to me, but just kind of talking in my direction, saying, “You know, I don’t think I can do this again.” She said, “I’ve lived here all my life, and I love living by this river. It’s such a beautiful thing to be by, and when it gets like this, you know, I just don’t think I can live through another flood.”

And so I was just thinking about all that as I was riding home, and the song kind of came out of that conversation.

“Ain’t I standin’ here like before/ The river’s in my blood/ If you’ve never lived here you can never understand.” Courtesy Chris Haddox.

“Ain’t I standin’ here like before/ The river’s in my blood/ If you’ve never lived here you can never understand.” – Courtesy Chris Haddox.

Kitts: Fast forward to today, after Hurricane Helene tore through western North Carolina, why did you decide to use this song as a fundraiser?

Haddox: I think we all, when we see something like that, our first reaction, as a species, is generally: what can I do to help? I woke up one morning, and that song was running through my head. And as I said in my little fundraising [post], “Can a song born of a flood help raise money for relief from another flood?” That was the idea that was floating through my head. So I just thought, “Well, I’ll donate it. You can buy the song for whatever” – I set a dollar minimum on it, and some people paid a dollar, some people paid $100, so that’s how it came about.

Kitts: Your music has these interesting connections to personal and community disasters – both the White Sulfur Springs flood and now the devastation that’s been caused by Hurricane Helene. What role do you think music can play during events like these?

Haddox: There’s a whole genre of disaster songs. Some of them are just a telling of a story, and in others, they’re really kind of tugging at the emotions in it. Maybe at some level, it helps just process what’s going on, to hear it coming back at you. You’re not just reliving it in your head. You’re hearing somebody else sing it.

And I think it has the opportunity to validate what you’re feeling as a person who maybe has gone through that and has experienced that trauma, to hear it out there, that you think, “Wow, it’s not just me that’s feeling this or thinking this.” It just seemed like maybe that’s what this song’s purpose was, to have some bigger impact than just being a song I sing in a show.

——–

At the time of this posting, Haddox had raised more than $2200 for the Presbyterian Disaster Assistance fund, dedicated to helping rural parts of North Carolina.

For more about Haddox, visit his website, Facebook or Instagram.