This story originally aired in the Aug. 27, 2023 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Flat Five Studio has frequently evolved to keep track with the rapidly changing music industry.

Now, as a new owner takes the helm, the studio is trying new things while still remaining grounded in the fundamental art of expert music production.

Located in Salem, Virginia, Flat Five Studio has been around since the 1980s. It was founded by Tom Ohmsen, who grew up around music. His uncle played trumpet in jazz bands, and bought him his first tape recorder when he was just a kid.

“I got just a basic quarter inch reel-to-reel recorder with a cheap microphone,” Ohmsen said.

Ohmsen’s family moved around but eventually settled in western Virginia. When Ohmsen went to college at James Madison University, he started playing his own music, beginning with a roommate’s mandolin. Ohmsen also got into college radio, which gave him the chance to practice his recording skills with high-level bluegrass musicians. He would travel to nearby festivals and eventually hosted musicians in-studio.

“Those people were demanding that somebody mix them according to the protocol of bluegrass and old time music, and I just happened to be in that world,” Ohmsen said.

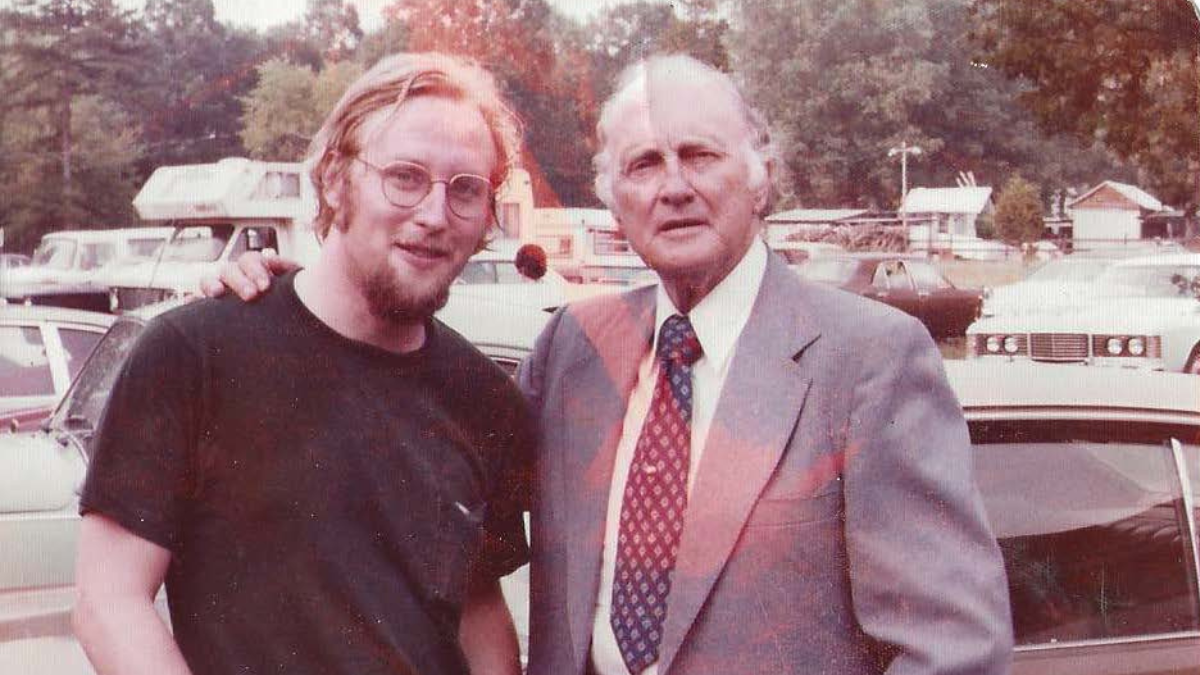

Ohmsen recorded bluegrass artists such as Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley and Seldom Scene. The experience gave him the chance to rub shoulders with famous musicians, while also honing his recording skills.

Credit: Mason Adams/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

Ohmsen eventually opened his own recording studio — first in his house and then in a space in downtown Salem, Virginia. Flat Five Press & Recording catered to local bands, and to bluegrass musicians who knew Ohmsen would record them properly.

Then, one day, Ohmsen got a call from the owner of a Roanoke-based sound and event company. It turned out a Charlottesville promoter was looking for a quiet, out-of-the-way place for a band to record an album. But there was a catch — Ohmsen had to keep it a secret.

“They tried to record at a studio in Charlottesville, and the recording was going okay, but there was such a buzz that they couldn’t get anything done,” Ohmsen said. “Crowds of people were showing up, because it was a local sensation. So it was this undercover thing for six or eight months.”

And that’s how Dave Matthews Band ended up at Flat Five.

They recorded between 150 and 200 hours for songs that became part of the band’s debut album “Remember Two Things.” The album was released in the fall of 1993. Soon after, Dave Matthews Band exploded in popularity, becoming one of the defining acts of the 1990s. That, in turn, made Flat Five a hot destination for bands hoping to make a splash.

Credit: Mason Adams/West Virginia Public Broadcasting

“I was swamped with regional and local bands,” Ohmsen said. “I was working six, seven days a week. But, it felt like I had to do what I could do with it while the demand was there.”

Flat Five became one of eastern Appalachia’s premier recording studios. Ohmsen kept rolling with it — at least until a few years ago, when he started to think about retiring.

“Last year, I turned 68,” Ohmsen said. “And I’m thinking, ‘I don’t know if I want to be here at 75.’”

Ohmsen made plans to pass on the studio to a new owner — but not one who would do things exactly the way he had. Instead, he zeroed in on one of his employees, a part-time engineer named Byron Mack. Mack grew up in the Roanoke Valley. And like Ohmsen, Mack came from a musical family.

“I am the nephew of the jazz singer Jane Powell,” Mack said. “My grandfather is the one who got her into music. His name was Eddie Powell. I’m a third-generation musician from my family.”

Courtesy Photo

But while Ohmsen got into bluegrass, Mack was all about rap and hip hop. His aunt Jane encouraged him to pursue it.

“So as a 17 year old, I was writing rhymes, and she found my rhyme book,” Mack said. “It had a bunch of profanity-laced stuff in it, just a young kid writing crazy stuff. But she was like, ‘Hey, you clean this up, I’ll let you come out and rap with my band.’ And that’s where everything started.”

Jane Powell did more than give her nephew a chance to perform. After he complained he was having trouble finding beats, she gave him a beat machine for his 18th birthday.

Mack was still living at home with his mom, but he quickly started producing music. Like Ohmsen, he started with a makeshift studio in his house.

“To tell you how small things were, I slept on a mattress, and I would literally take that mattress out of the walk-in closet so the artist could have room to go in and record their song,” Mack said. “And then when they’d get done, I’d slide the mattress back in the closet.”

Mack’s hustle and initiative eventually put him on Ohmsen’s radar. In 2005, Mack went to work at Flat Five. Ohmsen says it was a good fit from the start — not just on the technical end but with handling clients and soothing musicians when they started to get frustrated.

Mack says Ohmsen started talking to him about retirement in 2018. It took another four years to close the deal, but finally in 2022, Mack became Flat Five’s new owner. He has expanded it to incorporate more of his work in hip hop and R&B.

“I’ve been able to bring in some more hip-hop elements that didn’t exist before,” Mack said. “I still do graphic design [and] website design. We really try to make it a one-stop shop for an artist so they don’t have to go anywhere else.”

Courtesy

Mack has continued to work with Flat Five’s old clients, but he’s brought in new artists, too — especially hip-hop artists. Ohmsen said he thinks that’s the studio’s future.

But even with Flat Five’s long history, there are challenges. Flat Five is essentially a new business, with all the difficulties that come with it.

But then again, Byron Mack has been working as a music producer for decades at this point. Just like Tom Ohmsen, he started at home before moving up to Flat Five. He wants to keep building and turn the studio into a destination for musicians across the east coast.

“My long-term goal for Flat Five is to be that go-to spot when you have to travel through southwest Virginia,” Mack said.

And in doing so, Byron Mack is keeping Tom Ohmsen’s vision, and the craft of music production, alive and thriving.

——

This story is part of the Inside Appalachia Folkways Reporting Project, a partnership with West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Inside Appalachia and the Folklife Program of the West Virginia Humanities Council.

The Folkways Reporting Project is made possible in part with support from Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation. Subscribe to the podcast to hear more stories of Appalachian folklife, arts and culture.