Renowned actor James Earl Jones died earlier this month at age 93. Jones was part of the cast of the 1987 John Sayles film “Matewan,” which was shot in Thurmond, West Virginia.

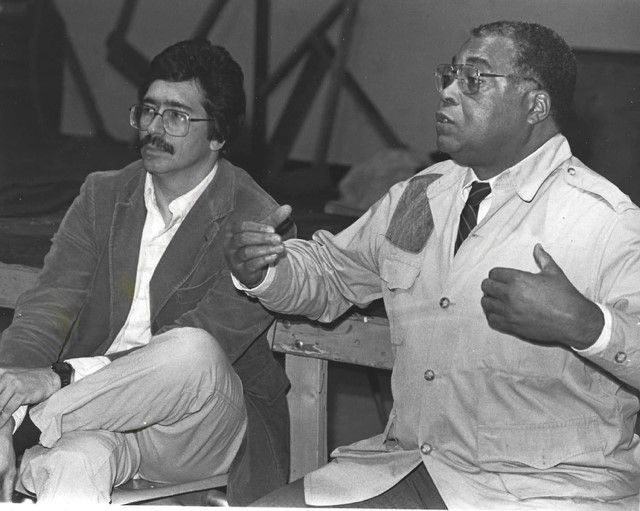

Curtis Tate spoke to David Wohl, who at the time was an acting teacher at West Virginia State and asked Jones to come speak to his students.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tate: Why did James Earl Jones come to West Virginia to be in Matewan?

Wohl: I think he chose the film because it was just an interesting acting choice for him. And I mean, Sayles was really lucky to get him at that point. But when you think about it, he had done the voice of (Darth) Vader in ‘Star Wars.’ He worked steadily, but he wasn’t a movie star.

His main work was in theater, in ensemble work especially. And he still continued to act on Broadway and in smaller plays. The first time I saw him was in a tiny play off Broadway. And then I saw him in ‘The Great White Hope,’ which was the show that won him the Tony Award for Best Actor when he was fairly young. This would have been the ’60s, I think, and so he’s not the star, like a Brad Pitt. He was in a lot of independent films, and he wasn’t a leading man at that point. He was an ensemble player, a character actor, and he knew that. So he chose projects that he thought were meaningful to him, and that’s one of the things I really respected about him, about his acting, and about the projects that he chose. So I think it spoke to him.

Tate: How did you get Jones to come speak to your students?

Wohl: So we had some faculty, we had students appear in the film. We’d been trying to get James Earl Jones as a speaker at State for years, and had no luck. Just on a whim, I knew the casting director [who] told me where they were staying, which is one of the motels in Beckley, the cast while they were down there, Econo Lodge, or one of the cheap motels that was out there.

Yeah, and I called a couple of times and just asked to speak to him, and sort of luckily, he actually answered the phone. Before he hung up, I said, ‘Hey, I’m a theater instructor at West Virginia State. It’s a historically black college. We’d love to have you come up for a day. I can give, I can give you probably, you know, 500 bucks or 1,000 bucks, and pick you up and bring you to campus.’ And he said, ‘I don’t know what the shooting schedule is going to be, but I’d love to do it.’ And I said, ‘Great.’ And so we traded phone calls back and forth, and when we scheduled one day and they had a shoot, he was called for that day. We couldn’t do it.

At the last minute, he said, ‘I’m free. Can someone come get me?’ I said, ‘I will send a student out and bring you to campus.’ Which I did. And I don’t even remember what month it was. I think it was winter, January, February. And I happened to be teaching my acting class that day at the fine arts building. He came in around 9 o’clock – I think my class was 9:30 – I introduced myself, and he sat down with the class for an hour and a half and talked about his experience and his career and acting tips. And he was just marvelous, just wonderful.

Tate: The film got many critical accolades, but few awards. Why?

Wohl: Because it’s not a studio film. They couldn’t publicize it. They couldn’t release it widely. It’s one of the difficulties that independent filmmakers have. Unless it’s a Marvel film, it’s tough, unless you’ve got backing. A lot of these films have gotten critically acclaimed, but they don’t make money, in terms of how much money you’re going to put up. They’ve got to do it on the cheap. Critically acclaimed doesn’t mean you’re going to be successful at the box office, you know? It’s not a feel-good film. It’s got a story. It’s slow in developing. The characters are really interesting, but it’s not an action film. It’s not a comedy, it’s not monsters, and so it’s always going to have a small audience, and that’s one of the difficulties in independent filmmaking.

Tate: One of the themes of the film that resonates today is that the union movement in the coalfields was a multiracial coalition. Whereas the coal companies tried to use racial differences as a wedge between workers to discourage them from forming the union.

Wohl: That’s one of the basic tenets of it. You got the Italians who settled in southern West Virginia who came over to work in the mines. You had the blacks, and then you had the poor whites. I think it was pretty accurate in terms of those sort of disparate communities and the union sort of bringing it together. I think that was one of the big messages that Sayles wanted to get across in the film by having these separate, identifiable communities, and then the whole idea of the union, then bringing it together in terms of commonalities.

It’s interesting. It’s pretty topical now in terms of the political environment, where we’ve got people trying to divide us because of our differences. I think what Sayles was trying to do was saying, we got more in common than you think. We all have to buy from the company store. We’re all living in these horrible conditions. We’re not better than anyone else. And I think that that’s part of the arc, message, of that movie.