A researcher at Marshall University has discovered an entirely new type of plesiosaur after studying the fossils of two creatures.

News Director Eric Douglas spoke with Robert O. Clark, the academic laboratory manager for the Biology Department at Marshall, to find out more. We’ll let him explain the name though.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Courtesy Robert O. Clark

Douglas: Let’s define what a plesiosaur is.

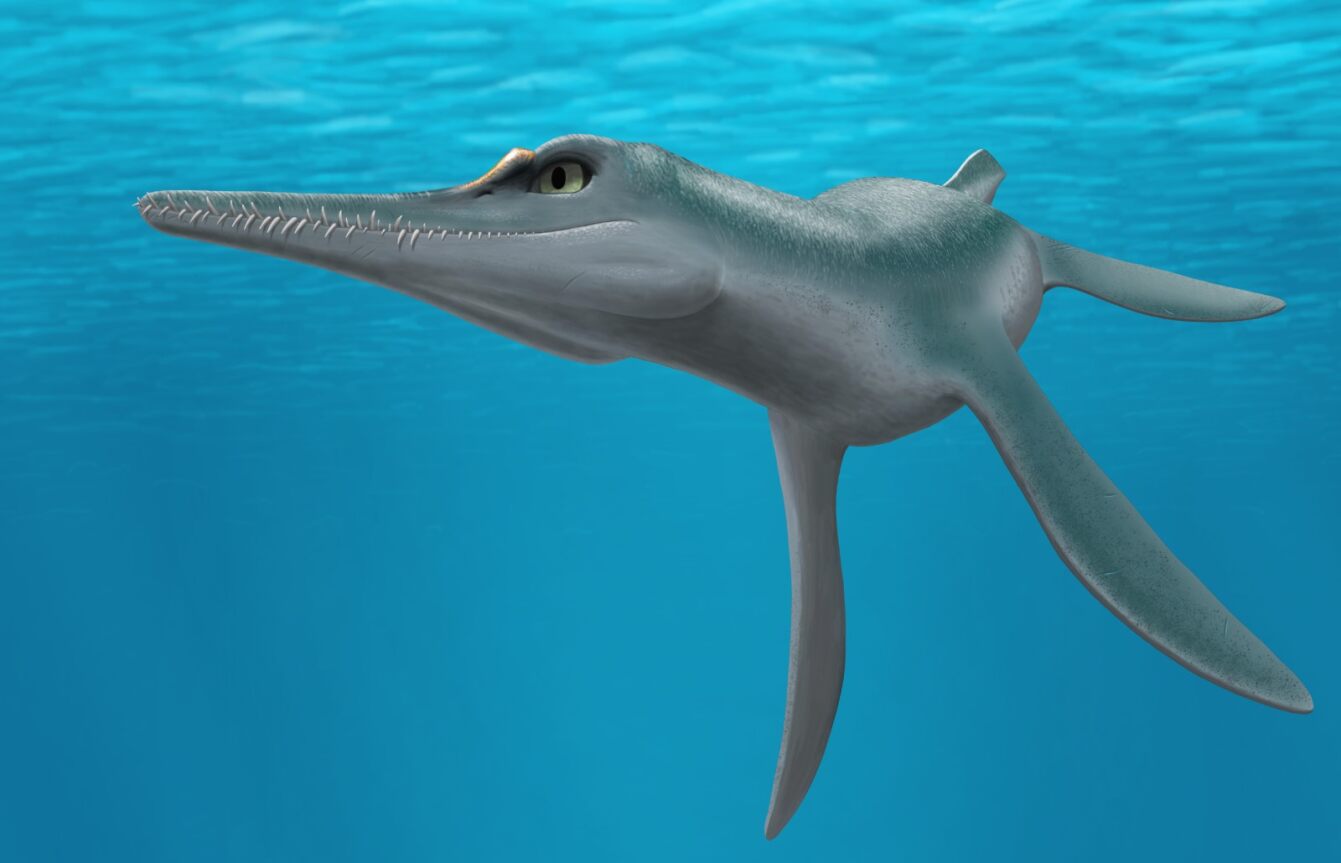

Clark: When I talk to people about plesiosaurs, I think it’s helpful to start with the Loch Ness Monster. So picture the Loch Ness Monster in your mind. And what a lot of people tend to picture is basically what a plesiosaur looked like. It’s this huge reptilian sea creature with a head with sharp teeth, a long neck, kind of a teardrop shaped body, and four flippers. But the difference is, unlike the Loch Ness Monster, plesiosaurs were actually real and they lived in oceans all over the world during the time of the dinosaurs.

They were a pretty diverse group. So they didn’t all actually have long necks. Some had short necks. A lot of them were huge. Some of the biggest ones were 40 to 50 feet long. But there were also smaller ones, too. And the type I study is actually one of the smaller types.

Douglas: What’s the process that you were studying plesiosaur and realized, hey, wait a minute, this isn’t something we’ve ever seen before?

Clark: It started actually before I came on board [with] my adviser here at Marshall, a plesiosaur expert named Dr. Robin O’Keefe. Marshall is an amazing school for Paleontology. Paleontology is kind of a hybrid between geology and biology, because we’re studying things that were once living, but they’re now entombed in rocks. And so we need to know about rocks and fossilization, and rock layers, but we also need to know about the living animal. And I’m way more interested in the biology side of things than like how things fossilized. I want to know what was this animal actually like when it was around? How did its body work? How did it fit into its environment?

Dr. O’Keefe didn’t pull it out of the ground himself. It was found by a paleontologist named James Martin in 1998 for the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. He [O’Keefe] was visiting them and realized the skull is something significant, and it’s not something that’s been described before. So they graciously gave us permission to work on that. When I became a grad student, you start anatomical comparisons and learning about plesiosaurs and this family of plesiosaurs called polycotylids and eventually realized that there’s this other skull over at the University of Colorado at Boulder that looks remarkably similar to the South Dakota skull.

Courtesy of Robert O. Clark

And so we start really comparing that and talking to those guys. That one was found in 1975 by a paleontologist named Ken Carpenter. The University of Colorado Boulder graciously allowed us to come and pick up that skull and bring it back to Marshall and really study it. They also have a nearly complete skeleton of the rest of the animal. And so we were able to travel out there a second time and spend a few days really analyzing the rest of the skeleton and realize these are the same animal and it’s a new type of polycotylid, unlike any other polycotylid plesiosaur that’s been found.

The neat thing, too, is it the same exact rock layer just 42 miles apart on either side of the border between those two states. We’re very confident they’re the same species and they’re a new species and genus.

Douglas: This is its own genus?

Clark: “Yeah! So one thing that sets this guy apart is this family of polycotylid plesiosaurs, they’re often around 15 feet long, [but] this is actually the smallest polycotylid plesiosaur known as an adult, at only around seven and a half feet long. It would look similar to a human in size if you were swimming next to it.”

It’s also fascinating because it has the largest eyes of any polycotylid plesiosaur known and they’re angled forward. So we think they had overlapping fields of vision. This thing could see with binocular vision and really zero in on its prey. We think this was a visually adapted predator and that’s one of the fascinating things about it.

Another thing about its eyes is it had these bony ledges over each eye. And we think the purpose of that was to shade them from the sun. Because eagles have a really similar thing over each eye. And this was really surprising to us that there’s parallels with predatory birds.

Douglas: It’s interesting how you can make those leaps. And I understand it’s a hypothesis, but you can make those leaps based on this. Other animals that we know of today look like this, and this is what they do so you’re filling in the blanks, right?

Clark: So much of paleontology is looking at living animals, and what did they do with these anatomical features? And not just theorizing about what would make sense in your head but what’s actually going on with real animals today.

Courtesy of Robert O. Clark

Douglas: When I looked at the background information on this, I realized I couldn’t pronounce anything. What is the name of the specific polycotylid plesiosaur you named?

Clark: This particular polycotylid plesiosaur we named Unktaheela. And the reason we named it Unktaheela is because it’s a Native American Lakota word. The Lakota people, their tradition tells of this mystical, horned water serpent that lived in the part of the country where we found these specimens. And that reminded us of a few things. It was said to have keen vision. And that reminded us of the visual adaptations. Horns reminded us of the bony ledges over its eyes. And then a water serpent that’s kind of like a sea serpent, plesiosaurs are kind of like sea serpents in a vague way, but it’s in the middle of the continent, which is weird for this water creature, but totally reminded us of the Western Interior Seaway. That was this huge inland sea that covered the middle part of the United States running from Canada all the way down to Mexico, essentially, dividing North America into two subcontinents. And that’s where this thing was swimming around. If you go out to the Midwest today, you can find all sorts of fossil shells and fish and shark teeth and fossil sea turtles and plesiosaurs like Unktaheela.

Douglas: What haven’t I asked that you want to talk about?

Clark: It’s been a longstanding debate, how did plesiosaurs swim? It’s really interesting because there’s nothing on earth, alive today that has basically two sets of underwater wings. They have these huge flippers. You think about a sea turtle. It’s swimming more with its front flippers, right? The back ones it’s more steering with. Plesiosaurs had huge rear flippers, too and they were swimming with these two sets of flippers, these two pairs of underwater wings. And so how does that work? There have been all sorts of models for that. And so that robotics thing was trying to show what the most efficient uses of these would be. It’s interesting, because [with] a lot of sea creatures, you think about an undulating body more like a fish or a dolphin.

Click here to view video and pictures of a swimming robotic plesiosaur.

But with plesiosaurs, they didn’t have a lot of flexibility in their body itself. It’s almost like a turtle, not with a shell but a really compact body. They had these pelvic and pectoral girdles that were just humongous and all these belly ribs called gastralia in between them, so a fairly rigid structure in their body. And so they weren’t undulating through the water. Instead, they were using their fore flippers and hind flippers to swim.

- The Unktaheela paper at Cretaceous Research: https://authors.elsevier.com/a/1iQMaiVLDN60B

- Biological Sciences at Marshall University: https://www.marshall.edu/biology

- Research updates from Robert O. Clark: https://twitter.com/RobbieOClark