Your browser doesn't support audio playback.

This conversation originally aired in the July 20, 2025 episode of Inside Appalachia.

Michael Snyder is a photographer and filmmaker who grew up in the Allegheny Mountains on the border of Maryland and West Virginia. His work has been featured in National Geographic, The Guardian and The Washington Post. After living away from Appalachia for over a decade, Snyder moved back to document what changed and what stayed the same.

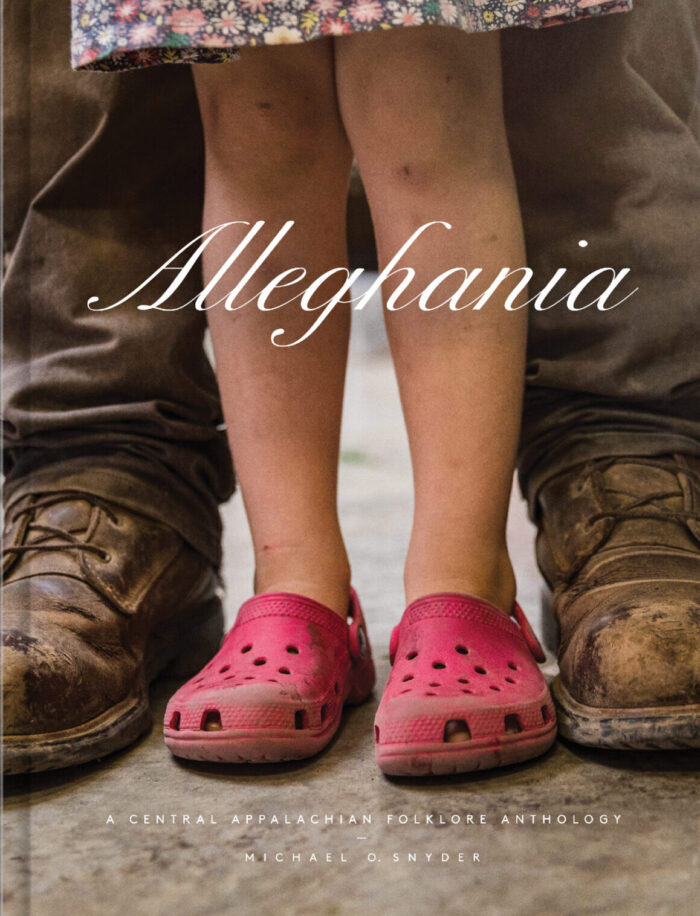

The result is a new book. It’s called Alleghania: A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology. Inside Appalachia Associate Producer Abby Neff recently spoke with Snyder.

The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

Photo Credit: Michael Snyder/Bitter Southerner

Neff: Michael, can you describe a photograph for us that you think best represents your new book, Alleghania?

Snyder: Yeah, gosh, this is such a hard question. There are so many images in this book that I love, and every one was a different little adventure that I got to go on for a day. So, it’s hard to choose, but I’ll start with one.

There’s one that I just love, and it’s titled “The Farmers.” It was a day spent on a small family farm right near the border of western Maryland and western Pennsylvania. We got up early in the morning – I think we got up at 5 or 6 in the morning – and we went out to pick apples in this orchard. We were walking up in this field and the grass is all overgrown and there’s dew everywhere. It was just really, really quiet, like one of those quiet mountain Appalachian mornings, and we just sat there. We must have been there for a half an hour just going along [and] picking apples. I was just waiting and waiting and waiting. As a photographer, you just wait for these little moments to happen. You kind of have them in your mind, but you hope that everything might line up. It’s just this photograph where all the pieces that I wanted – the little kids in the family, the mother, the dogs are all there, the apples and the dew – it just all kind of lines up perfectly. [It] just really, for me, just captures this feeling of what it’s like to be alive and be in the mountains and in the morning in this place. I think it’s just a lovely little moment. So, that’s one of my very favorites.

Photo courtesy of Michael Snyder

I’ll give you one more. There’s another one that is called “The Swimmers.” It’s about a swimming hole, and it’s … more of a traditional portrait with a father and his two children in this swimming hole, and he’s got a tire slung over his arm for a tire swing. I love this photo because growing up country, that’s what you did when you were a kid. You went out to the swimming hole, so it’s something I have very strong memories about doing. We got this sort of super masculine guy; he’s big and he’s buff and he’s in the river, but it’s such a sensitive photo. He’s just … gently carrying these kids, and the kids are so cute. I think it really speaks to a lot of what I wanted to explore in this book, which is looking at identities and stereotypes and then understanding that they exist for a reason, but also challenging them where that’s reasonable.

Photo courtesy of Michael Snyder

Neff: Why did you want to create an anthology about central Appalachia?

Snyder: Well, like I said, this is home. This is where I grew up. As a documentary storyteller, it’s always wonderful to get to work on a project about a place that you love. So, in a lot of ways, this is a love letter to where I’m from; a place that I grew up in and then I moved away from, like a lot of people in my generation. I moved out of the area for work and then came back later. When I came back in the 20-teens, what I saw was this place that I had known for so long was in many ways still the same; a lot of what I had known as a kid was still there.

But, there are some things that were radically different and were changing really quickly. I think, probably in the last 20 years, this region, Appalachia, broadly, and maybe more specifically, the Allegheny Highlands, where I’m from, it’s probably, arguably, undergone one of the fastest changes in its history. We’ve seen highways come in, the internet come in, the global economy [come in], so it’s a place that is opening up very quickly to the world. The world is seeing it, and it’s seeing the world, and at the same time, it’s one of the most stereotypical [and] traditional places in the United States.

So, I wanted to make a book that really explored that tension. How do we hold on to these identities and life ways and traditions that are endemic to the region or so personal to folks in Appalachia, but at the same time, make space for new things and allow the things that we love to change and to evolve and to open up the dialogue for new identities and new people to come in. What does that process look like right now?

That’s the question that I brought into this book and really drove it by rather than me trying to answer that question as one person, really trying to understand that through the perspectives of people that are from there. A lot of what we hear about Appalachia comes from people on the outside, and you can do great work as an outsider, but I was really curious about what people from the place had to say about what that looks like.

Neff: Your past projects have taken you all over the world. How did creating Alleghania compare to those experiences?

Snyder: My work as a documentary photographer is kind of split in half. Half of it is in far flung regions around the planet; I’ve worked in the Arctic, and I’ve worked in the Himalaya. I’ve been privileged enough to work in places like the Amazon and far corners of Australia. And then the other half is in Appalachia. Seemingly, those are very different things, but I think the truth is [that] what it looks like and feels like to do documentary work is really just to get access and permission and privilege to be in somebody’s life for a day. And certainly, whenever you’re working in a place that’s home, that comes natural, right? You have more of that shared language and that shared identity and that shared culture to build off of. But still, fundamentally, it’s about getting real trust and real permission to share a story of somebody who you don’t know yet.

So, that’s a challenge no matter where you work and it’s an adventure no matter where you work. You really don’t have to go around the planet to be on a great adventure. As a storyteller, I see the work that I do in Appalachia is in many ways, just as exciting and just as enriching as things that I’ve done elsewhere.

Photo courtesy of Michael Snyder

Neff: How does this project challenge the “stranger with a camera” trope that seems to endure in Appalachia?

Snyder: A place like Appalachia has been a curiosity to people for a long time because of its inaccessibility, because of its unique culture, because of how synonymous it is with American traditions and Appalachian traditions, and also because of the poverty and the hardship. A lot of that is positive and really honorific of the region, but some of it less so. I think, particularly when you have folks on the outside that come there to sort of engage in poverty porn, to just really look at what’s negative and to go and try to capture that and be extractive and take that away for external entertainment, I think there’s some real ethical questions about that.

As a documentarian, as an outsider, it’s very difficult to know what the right questions are to ask, who to speak to, who not to speak to, and so on. I will say that I do think there is excellent work done about any culture that can be done externally to it. It’s not a given that if somebody is from a place, they are going to tell something that is of high integrity and high quality and so on. So, it isn’t as simple as that, but certainly by being from a place, you’ve got a leg up on all of that. The way that I try to do all of my projects, and especially this project, is to really be collaborative in the storytelling. Whenever I’m approaching folks to talk about various traditions – and this is a book fundamentally about traditions: what these traditions are and how they’re changing and how they’re staying the same – I start that as a dialogue with the people that I’m working with.

You tell me where you think this conversation should go and what it should look like, and you help guide me towards what photo you think will be most representative. So, that’s a little bit different than traditional photojournalism, where the idea is to be purely objective and to kind of drop in from the outside and capture something that’s your unique voice that is unobstructed. For me, as a documentary photographer, somebody that does that in a way that I hope has a lot of reciprocity and community building built into it. I really want to do that with the communities that I work in. Whenever I make a project, I hopefully make it for an international audience, but in a real way, it’s made for the people that, that the project is about. So, I’m most excited to give this work back to the community. Whenever I have published this work in the past, or whenever I’ve done gallery shows and so on, the first place I want to bring it is back to the community that I made it for.

I’ll just kind of close my thinking here with one final idea. As I said, I’m a teacher now. I teach documentary process, and one of the things that I consistently say is both the practice, the process and the output of documentary work should be relationship building, right? That’s what the work is. It’s building relationships. Building relationships obviously [with] the people that you’re working with but hopefully helping them to deepen their own relationship with themselves and the place that they know and they love, and building bigger connections between the community that you’re working with and the outside world. So, I see myself as a photographer and a storyteller, but in a big way, as a relationship builder, as well.

Neff: Who should read this book?

Snyder: Certainly, my hope is for the people in the region to. I think, oftentimes, as folks in Appalachia, the narrative that we have of ourselves is one that has come from the extraction economy, and that is a very negative narrative. It’s a narrative that we’re very monolithic in identity and we don’t know how to take care of ourselves and we’re poor and a little bit hopeless. I think this book really challenges that. I think it challenges the stereotype that we’re not a diverse place. There are, of course, ways that we are not, but diversity is an incredibly complex thing. There are so many ways that a culture can be diverse, and I think when you start pulling back the surface layers of this region, you find a place that is incredibly diverse.

I hope people look at that and come to understand themselves in those terms. This is an old dialogue, but it seems to be something that is very much in the modern mind today, that there’s so much that divides us and maybe there’s more that divides us that we can possibly overcome. I just want people to really challenge that, because I think once you start talking to people, once you get beyond that outer shell of the politics that we wear or the color of our skin or identity or the region that we come from or whatever, there is truly, profoundly, far more that binds us and far more that we have in common that we share. So, I hope this book is a tool that continues that dialogue nationally, but especially in Appalachia, and continues to be in support of a force that brings us closer together and allows us to look at what we love and what we share in common.

——

Alleghania: A Central Appalachian Folklore Anthology is available from the Bitter Southerner.