Recent data from the Office of Drug Control Policy has revealed a decline in opioid overdose rates, marking a positive turn in the fight against the ongoing drug epidemic.

West Virginia overdose rates are slowly falling to pre-pandemic levels. Advocates say while this data is preliminary, this improvement is in part credited to in-person harm reduction services resuming after the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to provisional data, the state’s overdose rate fell from February 2022 to February 2023. The data shows that opioid overdose rates have dropped by approximately 8 percent, marking the most substantial decrease since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Yes, we are seeing less people overdose, and I think there’s a variety of reasons for that,” Michael Haney, director of PROACT, said. “I think West Virginia has done an excellent job in keeping the substance use problem in sight.” PROACT is an addiction treatment center in Huntington.

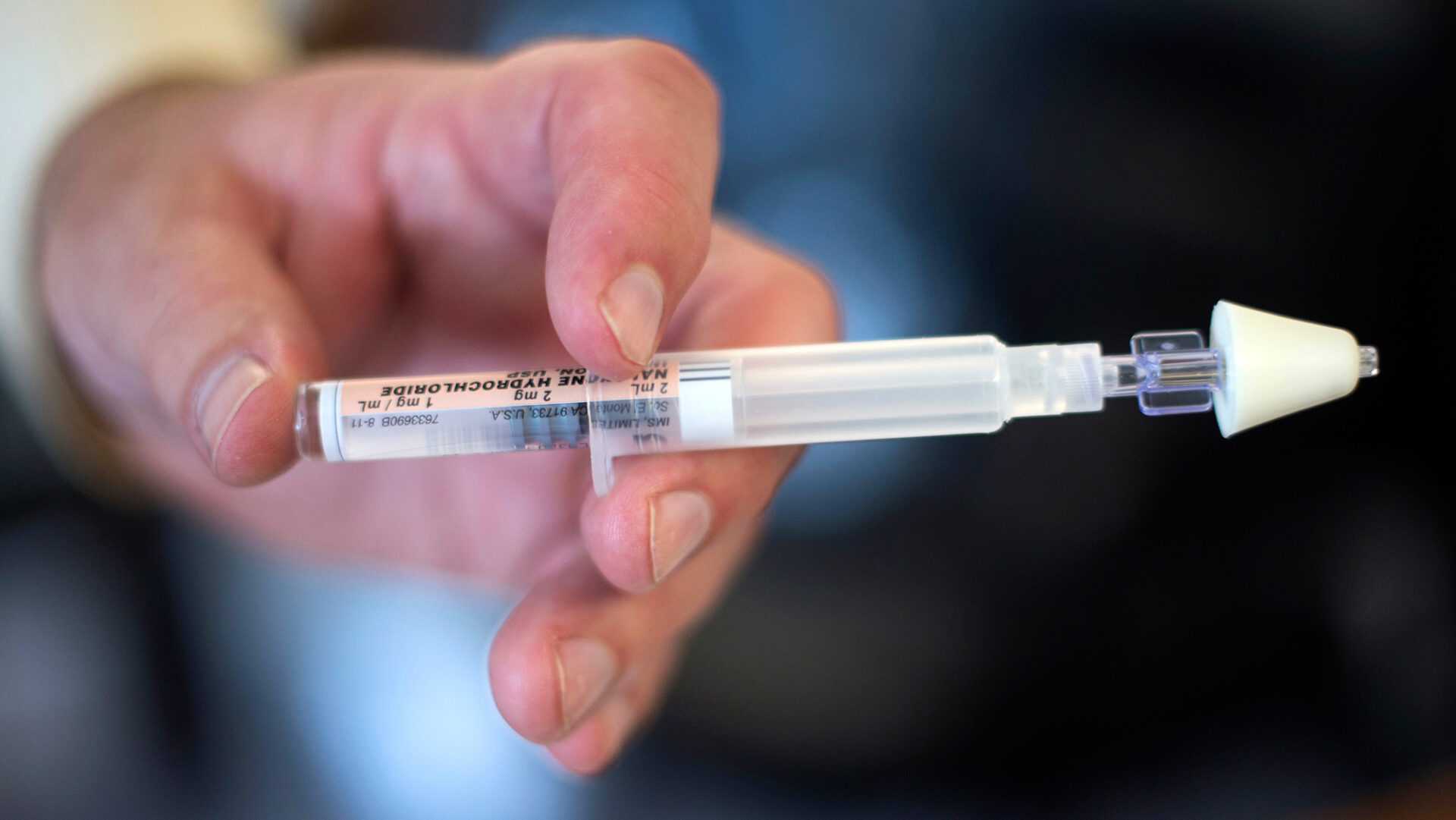

Health officials attribute the positive trend to a combination of factors, including expanded availability of naloxone, a medication that reverses opioid overdoses, as well as the implementation of harm reduction programs. Harm reduction refers to a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use.

“The drug problem has been there for decades. I think it really didn’t get people’s attention until you suddenly had people in large numbers dying, and you can’t attribute it to anything else, it was obviously the drugs doing it,” Haney said. “I think that calling attention to that, supporting treatment efforts, encouraging people to get into treatment. I think medication-assisted treatment has helped a great deal.”

West Virginia was one of only eight states in the nation predicted to see a decline in overdose fatalities in 2022. While the data is still preliminary, some advocates are encouraged by the success of harm reduction programs and public education since the end of the Public Health Emergency and COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Fatal Overdose Data Dashboard, West Virginia lost 1,453 people to overdose deaths in 2021.

A Changing Landscape

Lyn O’Connell, associate director for the Division of Addiction Sciences at Marshall University’s Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, said it is important to note only four months of data are available for 2023.

“We do know that drug trends vary throughout the annual calendar year with some rhyme and reason and other times without much explanation,” O’Connell said. “We do suspect that drug overdose deaths are changing in that the type of drugs being utilized are changing.”

Of those deaths, 1,146 were attributed to illicitly manufactured fentanyl, 103 to heroin, and 295 to prescription opioids. Overdoses occur with other drug types as well, including stimulants, to which 949 West Virginians lost their lives in 2021.

O’Connell said PROACT, Project Hope and programs like it had made significant amounts of progress in her community in 2019.

“The pandemic destroyed that. We had to pull a lot of people out of public spaces,” O’Connell said. “In general, as a community, people resorted to substance use, because they didn’t have to get up and go to work. It’s often a disease of despair, and it was very easy to feel despair during 2020 and 2021 especially. People lost their jobs, so it might be easy to turn back to drug use or selling drugs.”

In 2019, West Virginia lost 870 lives to drug overdoses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). During the COVID-19 pandemic, from 2019 to 2022, the state’s overdose death rate went from 870 to 1,453, a 67 percent increase.

“So we built on it over the past year, but it was going to take a while for us to see those things go into effect again,” O’Connell said. “I think the hope is that we do stabilize and or see a downward trend.”

Haney said isolation encourages use and is one of the major problems with substance use disorders. Alternatively, peer recovery programs like the ones offered at PROACT, encourage people with substance use disorder to interact with fellow peers in recovery.

“Now that we’re coming out of COVID, we’re back to doing in-person services, people are going too, and a lot of things happen when you do in-person services,” Haney said. “There is that sense of accountability that patients have when they’re going to treatment. They also get to see other people who are in treatment, and they have that sense of shared experience.”

Advocates say a rise in methamphetamine use is concerning and took the lives of 786 West Virginians in 2021.

“There’s other factors, there’s the use of methamphetamine, the use of xylazine, the use of alcohol or marijuana,” O’Connell said. “And so there are other things that impact how we can determine the effectiveness of, or if there is any decrease because there are just so many factors at play.”

Five of the most frequently occurring opioids and stimulants – alone or in combination – accounted for 71.5 percent of overdose deaths in 2021. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl and methamphetamine topped the list with 28.8 percent of deaths.

The use of multiple drugs at once accounted for 52.1 percent of 2021’s overdose deaths on opioids and stimulants.

Erin Winstanley is a research scientist in the department and associate professor at West Virginia University in the Department of Psychiatry.

She also encouraged vigilance, especially against new cutting agents appearing each day.

“I think many clinical researchers and researchers working in the field of addiction are concerned about the increasing number of people using illicitly manufactured fentanyl,” Winstanley said.

While the decline in opioid overdose rates is undoubtedly positive, experts caution against complacency.

“I think from the national perspective, it is too early to say whether overdose deaths are declining,” Winstanley said. “So it does appear that the numbers are on a downward trend. But it isn’t clear if they’re going to return to a pre-pandemic level.”

Appalachia Health News is a project of West Virginia Public Broadcasting with support from Charleston Area Medical Center and Marshall Health.