This conversation originally aired in the July 2, 2023 episode of Inside Appalachia.

West Virginia marked the 160th anniversary of its statehood in June.

Many residents of Appalachia have heard the history of how the state split off from Virginia during the American Civil War, or maybe even learned about it in a school classroom.

The basic story goes like this: During the war, people in Virginia were divided over whether to secede or stick with the Union. Eventually, West Virginia formally split into its own state, which was admitted into the Union on June 20, 1863 — what’s now celebrated in the state as West Virginia Day.

Inside Appalachia Host Mason Adams recently spoke with Hal Gorby, whose lecture on West Virginia statehood was recently featured on C-SPAN’s Lectures in History series. Gorby is a professor at West Virginia University (WVU), who specializes in Appalachian and West Virginia history.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Adams: What’s the biggest misconception that people have about West Virginia statehood?

Gorby: I think there’s a couple of common misconceptions, some of which have been replicated for generations through the way students learn about the statehood period. The best way I would explain it is this: The argument that the creation of West Virginia was inevitable — that from the beginning of Virginia’s history, there were stark cultural, economic, political differences and geographical differences of the mountains that made this process something that was going to happen.

I think the other misconception has to deal with the role of slavery. In western Virginia, it’s sometimes simplistically made out that there was not much slavery here. There were not the same number of slaves west of the mountains as there were in the east. But in most counties of the state, there were slaves. There were human beings in bondage. It does play a key role, and it plays a key role early in some of the early steps of the statehood process, and why certain areas of the state are more supportive of the Union, while others might have been more supportive of secession.

Adams: Let’s pick it up with the Civil War and that vote to secede in Virginia.

Gorby: When South Carolina seceded from the Union, right after [Abraham] Lincoln’s election, many of the southern states had secession conventions. Virginia’s is the longest. Statewide, delegates were chosen for a convention that was held in Richmond, starting in January and lasting well through the firing on Fort Sumter. There were a decent number of delegates from what’s now West Virginia. The delegates met for a number of weeks and very much debated the merits of secession — really fearing the fact that if there is a civil war, and Virginia secedes, the first state that’s going to be invaded by the Union Army is going to be Virginia. There was hesitancy to join with the southern Confederacy. But the firing on Fort Sumter and then Lincoln’s call for volunteers really changed things.

The convention finally votes to secede from the Union. It’s by a vote of 88 to 55 for secession. Of the 55 no votes against secession, 42 of them are delegates from what’s now West Virginia. The convention votes on April 17 and secedes. But they want to give ordinary people their chance to vote on what they think. Several weeks later, scheduled for May 23, 1861, the residents of Virginia will participate in a referendum. It is a vigorous vote.

About a week or so before, there are a group of western delegates who go to meet in downtown Wheeling, Virginia. There they discuss these broad ideas of what needs to happen. There’s a divide about whether the focus should be on pushing back against the secession vote or whether there should be a broader push to try to create a new state. That idea of creating a new state really doesn’t get traction. They decided to go back to their home counties trying to encourage voters to vote to stay in the Union to show loyalty to the United States.

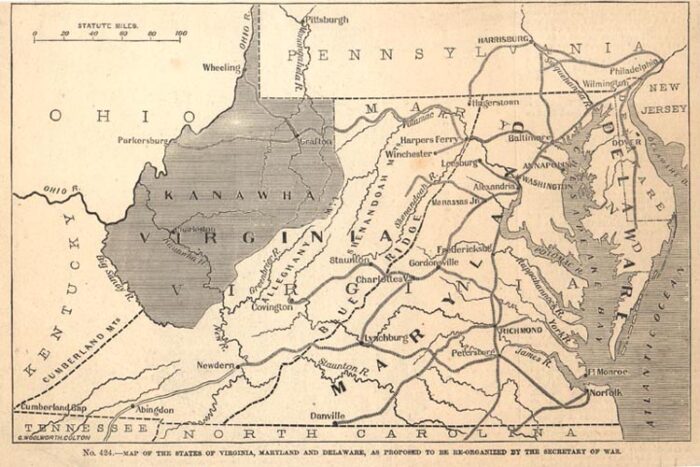

When that vote happens across the state, it reveals some interesting trends. Virginia obviously voted to secede from the United States. There are a number of counties in the western reaches of the state, from Hancock County to the north all the way down to Wayne [County] and Kanawha County in the Kanawha Valley, that vote to stay [in the Union]. The interesting thing though, if you look at a county-by-county map of this, there are 24 counties of what becomes West Virginia that vote to secede. That’s about half.

It’s mainly the deep southern now-coalfield counties, the central part of the state, and most of the counties that border Virginia all the way from Monroe County up to about Hampshire County. They all vote to secede. Then there’s a dividing line clearly around where the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad runs through the northwestern tier of the state and where the heavier populated towns like Clarksburg, Fairmont, Wheeling and Parkersburg. Here there’s much stronger support for staying in the union. But the divide is almost 50/50.

Adams: You start with that map. But then as military operations begin, the Union controls differing territories, and there are battles in some of these counties. Eventually, the state as conceived grows. Why don’t you walk us through what happens?

Gorby: As soon as the secession referendum happens, the Union army moves into western Virginia. They move across the line into Parkersburg, Wheeling, and they secure most of that area that had voted to be loyal to the Union. Around the same time, those delegates that had met in Wheeling prior decide to meet again in Wheeling in late June. With this sort of security — the Union Army present — there is really a discussion now about what the next step needs to be. The delegates basically come to the conclusion in this second Wheeling convention that yes, we want to first form a loyal government loyal to the Union that sort of reconstitutes the government of Virginia, now that the government in Richmond has now left the United States. And then, we want to show our support for the Lincoln government and for the Union effort.

Among many of them, there is this idea that, well, maybe it’s time, as John Carlile says, to cut the knot. Now that Virginia seceded, and we have a civil war, and we have battles that are taking place, maybe it’s finally time to make this move. They reconstituted the government. They choose representatives for state Senate, House delegates. They choose representatives to fill the open seats in the House of Representatives in Washington. And as this process goes on, eventually there is sort of a push to say, “yes, we’re going to create a new state west of the mountains.” It’s still early in the war. So issues like emancipation aren’t really top of mind on the list of issues. But this is to give them now control over their own destiny, so to speak.

Adams: To fast forward a little bit, eventually the process moves forward. Virginia has seceded. The Union part of the state moves forward with this statehood act in Congress. Anyone who’s read a biography of Lincoln, there’s usually a scene showing what he’s thinking in the days before he issues the Emancipation Proclamation. But one thing I learned from listening to your lecture was that at the same time he was considering the Emancipation Proclamation, he was also considering a bill for West Virginia statehood.

Gorby: Yeah, he had been tacitly supporting this effort. He was very careful. Partly for him, it was viewed as part of a goal maintaining the support of the border states. He saw western Virginia as probably the most important militarily, but by the time the bill that goes through Congress makes its way to his desk, he has choices. He asked his cabinet to give him their opinion. Lincoln’s cabinet often frustrated him. [This time,] three of them support the statehood bill and three of them are opposed, leaving it to President Lincoln to make the ultimate decision.

Yet, he actually waits until pretty much the last minute to make his decision on this. He is debating this along with the Emancipation Proclamation, which he’s actually more secure about. It’s the statehood bill that constitutionally worries him as a precedent-setter. He does agree to it at the end of 1862 in a very short, but very logically argued signing statement. He argues that [admitting] West Virginia is an expedient to the goals of ending the Civil War militarily. It’s part of this goal of keeping the border states in the Union and making it easier for the Union army to launch its attacks into the South. He argued that precedent in times of war will not be a precedent in times of peace.

Adams: In some of the reading I’ve done, there’s a mention to the story of a postscript, which I believe is the state constitution rewrite in 1872. Do you mind just addressing that briefly?

Gorby: After the Civil War, it’s a very divisive period, because West Virginia is not under federal reconstruction. It was a loyal state during the Union. But as I mentioned, earlier on, about half the counties had voted to secede. And it actually sent large numbers of Confederate troops. So when the war is over, many of these folks come back thinking that they’re going to just re-enter their normal lives, and many of them had been very much involved in state and local politics. They really tried to crack down on some of those efforts of ex-Confederates.

A few years later, they propose a compromise — to basically say we support allowing all African Americans to vote as the amendment to the U.S. Constitution, we will also, in exchange, allow all white men over the age of 21 to vote. So basically to say, there will be no restrictions on voting, by race or by association during the Civil War, as a compromise. Well, unfortunately, all those ex-Confederates now that can vote, they’re voting mostly for the Democratic Party. Of course, the state government is mainly now the Republican Party.

In the 1870 elections, they win basically almost all the seats. They have almost flipped the entirety of state government. One of the first things they tried to do is to move to have a referendum on a new constitution, which passes very narrowly. In 1872, they rewrite the constitution. Most of the elements of the way our state government operates were largely set by that 1872 constitution, which gave local control at the county level mirroring how it existed under the Virginia government prior to the Civil War.

Some of the issues about land ownership and the whole transfer of land ownership that’s going to happen in the late 19th century with industrialization is also put into that constitution as well. But that constitution does not discriminate against African Americans. So again — showing how different West Virginia is as a border state in the years during and after the Civil War.