A new study links the epidemic of severe lung disease among coal miners to toxic silica dust. The findings echo a 2018 investigation by NPR and the PBS show Frontline.

Exposure to a toxic rock dust appears to be “the main driving force” behind a recent epidemic of severe black lung disease among coal miners, according to the findings of a new study. Lawmakers have debated and failed to adequately regulate the dust for decades.

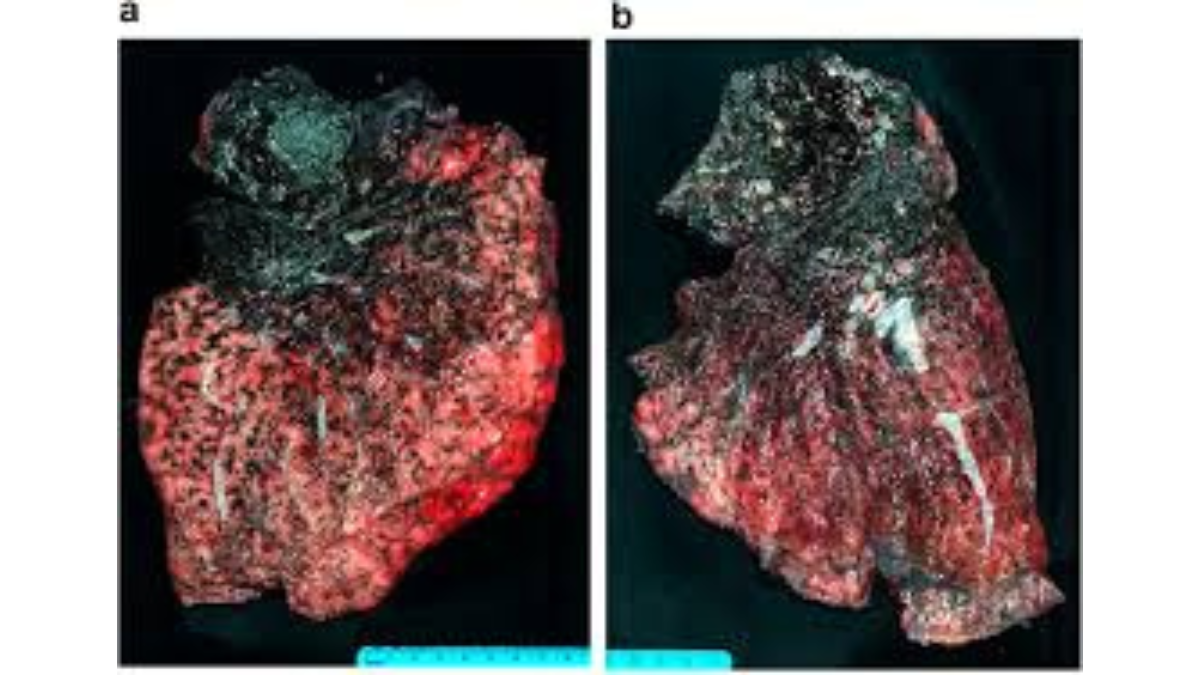

The study, which examined the lungs of modern miners and compared them to miners who worked decades ago, provides the first evidence of its kind that silica dust is responsible for the rising tide of advanced disease, including among miners in Appalachia.

“This is the smoking gun,” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Robert Cohen of the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. Cohen says that up to now there has been indirect evidence of the link, but his study went further – testing lung tissue samples for the concentration of silica particles.

“It turned out we were right. The pattern of pathology was very, very consistent with silica,” Cohen says.

Cohen’s study specifically looked at contemporary miners with severe disease, and what was lodged in their lungs, compared to older workers who also had severe lung disease.

Among their findings was that the more-contemporary workers – those born after 1930 – had more silica in their lungs than the miners who were born between 1910 and 1930.

Cohen’s work supports the findings of a joint investigation by NPR and the PBS show Frontline published in 2018.

NPR and Frontline found thousands of recent cases of the severe disease, known as complicated black lung or progressive massive fibrosis, in just five Appalachian states. Among them were miners in their 30s who experienced a rapid progression to advanced lung disease.

By analyzing decades of federal regulatory data, NPR and Frontline found thousands of instances where miners were working amid dangerous levels of silica. What’s more, the investigation found, federal regulators knew about excessive and toxic mine dust exposures but didn’t act – retaining an old regulatory standard for mining dust that doesn’t directly address silica.

Silica exposure comes from miners cutting into sandstone as they mine coal, which has become more common in recent decades as larger coal deposits were exhausted in Appalachia. As the mining machines operate, the quartz in the sandstone turns into sharp silica particles that are easily inhaled and can lodge in the lungs permanently.

Cohen and others are calling for the federal government to toughen Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) regulations on silica dust in mines.

United Mine Workers of America president Cecil E. Roberts tells NPR in a statement that the study “proves what we have already known, that silica is a leading cause behind the rise in cases of progressive massive fibrosis.

“I testified before Congress in 2019 on this exact issue and nothing was done,” Roberts says. “Now there is no excuse. MSHA needs to act to enforce a silica standard to protect today’s miners. Failure to act risks the lives of thousands.”

Shortly after President Biden took office, the Labor Department’s Inspector General said MSHA’s 50-year-old standard for regulating silica dust was “out of date” and difficult to enforce.

Mine regulators at MSHA have said they are studying a possible update to the regulation, which remains less stringent than the silica standard for other industries.

“I’ve heard good things from the Biden Administration,” Cohen says, “but we’d really want to push this through while we have good data and political motivation to do it.”

For its part, the National Mining Association, a trade association for mining companies and equipment makers, has argued that the amount of silica found in mine dust samples has decreased in recent years, and has urged regulators to allow mining companies to use personal protective equipment as a strategy to comply with any new silica standard.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.