This story has been clarified to reflect that the penalty phase of the trial will take place at a later date.

A federal judge in Charleston has ruled against Union Carbide, finding the company in violation of federal law over a hazardous materials site in South Charleston.

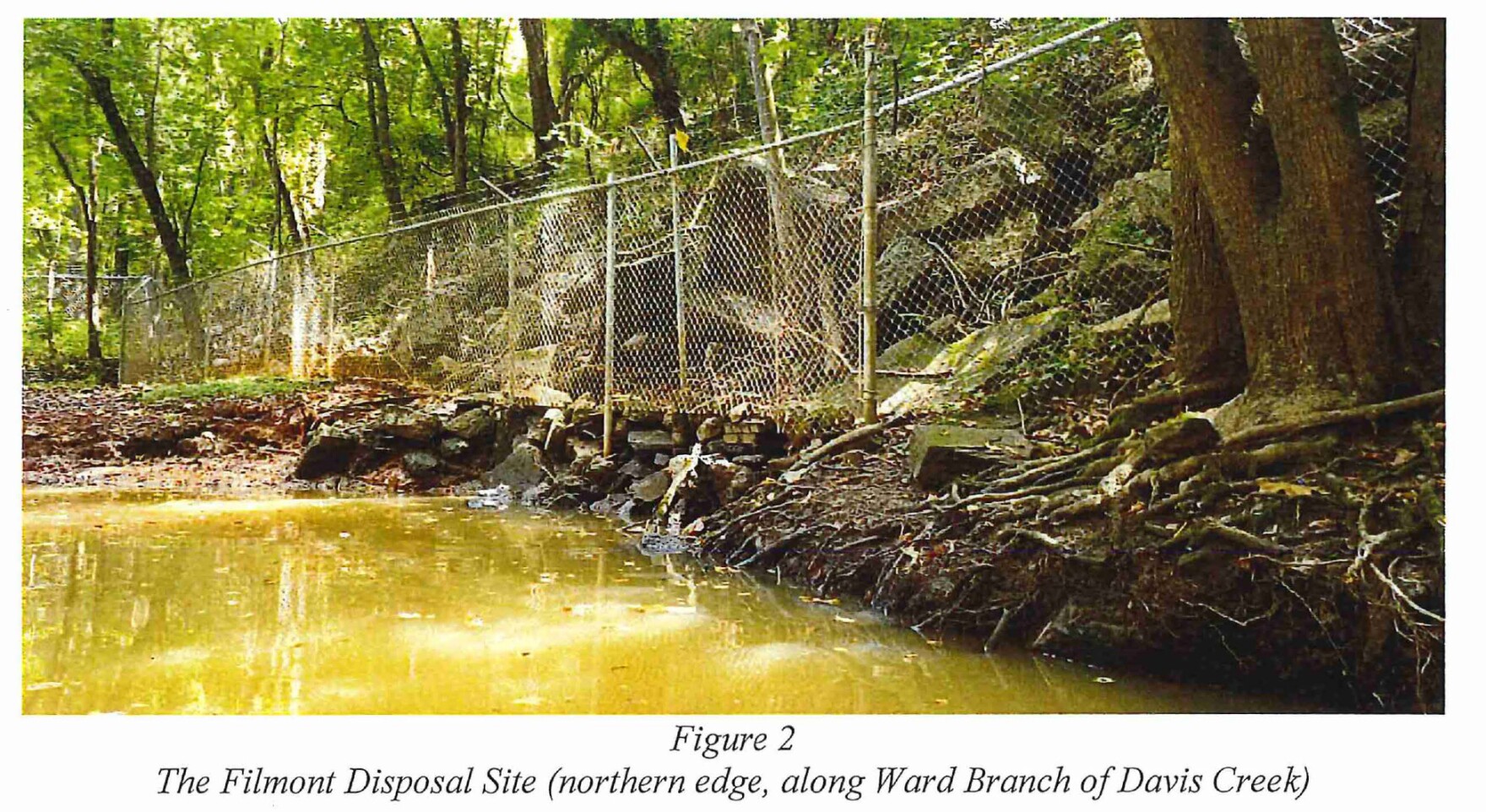

Judge John T. Copenhaver Jr., of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia, in a 400-page ruling dated Sept. 28, said Union Carbide is responsible for the cleanup of the Filmont site, where numerous hazardous substances were dumped from the 1950s to the 1980s, under the federal Superfund law, or CERCLA.

Copenhaver ruled the Filmont site violated the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, creating an illegal “open dump.” Union Carbide also violated the federal Clean Water Act, which required the company to seek a permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for stormwater runoff from an adjacent railyard it owns.

Copenhaver’s ruling mostly favors the Courtland Company, which had first sued Union Carbide in 2018 over contamination of its property from the Union Carbide landfill and railyard.

Copenhaver dismissed two of the pending lawsuits against Union Carbide. And he also ruled that Courtland is responsible for cleaning up contamination on its South Charleston property that was not caused by Union Carbide.

Both properties are adjacent to Davis Creek, a tributary of the Kanawha River. The Filmont landfill is located in the city of South Charleston, down the hill from the Union Carbide Tech Center, which is also on the Superfund list, and across Davis Creek from where the West Virginia Division of Highways is performing major construction on the Jefferson Road interchange.

The penalty phase of the trial will take place at a later date.

The case was the subject of an 18-day trial in Charleston last year.

Union Carbide had argued that it was not required to remediate the site under CERCLA, the site was not an “open dump” and it was not required to seek a permit from the EPA.

Copenhaver, 98, is one of the last active federal judges nominated by President Gerald Ford. Copenhaver was confirmed to the federal bench in 1975.

Union Carbide is a subsidiary of Dow Chemical.

View previous reporting on this issue from West Virginia Public Broadcasting here.