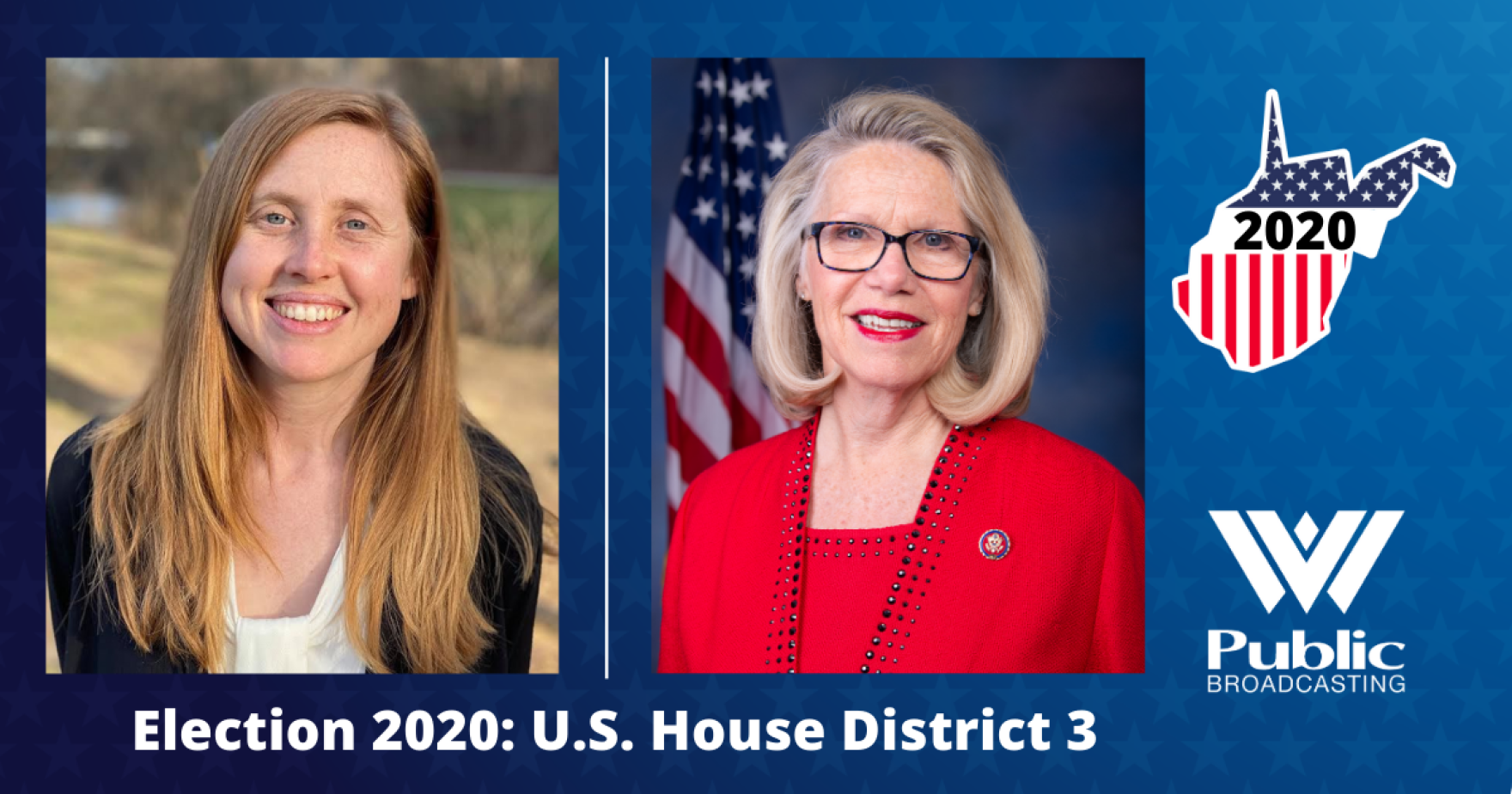

West Virginia’s Third District Congresswoman Carol Miller is up for re-election, and she’s running against Hilary Turner, a political newbie with progressive support.

The two women are squaring off in what was once a long-time Democratic stronghold. But even before its U.S. House seat recently shifted red in 2014, District 3 has always held a long history of extraction and social conservatism.

“Democrats in West Virginia, especially Southern West Virginia, consider themselves West Virginia Democrats, not national Democrats,” said former Democratic Congressman Nick Rahall — the state’s longest-serving House Representative, who represented southern West Virginia for almost 40 years.

“They don’t associate that much with the National Democratic platform,” Rahall said.

Since 2004, the southern counties have voted for a Republican presidential candidate in every election. But it wasn’t until Donald Trump’s victory in 2016, Rahall said, that local politicians began modeling their campaigns after his endorsement.

Enter Carol Miller, a former House Delegate, Huntington-area real estate agent and bison farmer, who tells voters that she’s pro-coal, pro-life, pro-border and pro-Trump.

“I mean, for every question she got asked there was a written statement response that always started out with how much she loved Donald Trump, loved the Bible and loved our country,” Rahall said of her campaign in 2018. “She was relying on Donald Trump’s coattails to get elected, and it worked. You can’t argue with success.”

Miller’s opponent Turner is banking on more progressive endorsements for her win, including support from the West Virginia Working Families Party and the West Virginia Can’t Wait movement. She’s campaigning on some of the same issues that the national Democratic party advocates for — universal healthcare, sustainable agriculture and a plan to address climate change.

“Far too long, we’ve had basically millionaire and billionaire politicians, buying their seats in office and catering to corporations,” Turner said. “And [they’re] leaving working people and working families behind. It’s just time for a huge shift.”

Going From Majority To Minority

Before Congress, Carol Miller served for about a decade in the West Virginia House of Delegates. Miller has lived in West Virginia for about 45 years, practicing real estate in the Huntington area and farming bison with her husband since the 1990’s. Her father was longtime Ohio Republican Congressman Samuel L. Devine.

While Miller’s win was one of several Republican victories in the West Virginia, she was the only newly elected Republican woman to win a race for the U.S. House in 2018 when that chamber flipped blue. At a bipartisan conference for women legislators, sponsored by Politico at the end of 2018, Miller said she looked forward to finding common ground solutions with lawmakers across the aisle.

“I have served in the minority before,” Miller said, referring to most of her time as a West Virginia House Delegate. “I knew even then that the most important thing is finding people of like mind in both parties, and working on policy that way. And that is the way I will continue to behave, and to learn.”

When it comes to legislation that Miller has co-sponsored, Govtrack reports Miller has been more centered than other members of her party.

However, FiveThirtyEight reported that in voting, Miller sides consistently with Trump on bills that he has publicly supported or opposed, while tracking from ProPublica shows that Miller has voted against her Republican colleagues less than 4% of the time.

‘You Need To Be Willing To Talk About Climate Change’

Miller declined requests from West Virginia Public Broadcasting for an interview through her campaign. Miller did agree to provide a few written responses over email.

Turner, meanwhile, agreed to an interview with WVPB, during which she said that she believes her stances on climate change during the June primary were far more advanced than that of her three Democratic opponents.

“I didn’t see a candidate that was talking about climate change,” Turner said. “That was a sign that maybe I needed to run for that seat, because I think running as a Democrat in 2020, you need to be willing to talk about climate change.”

Turner is a young mother who grew up mostly in Florida, but has deep roots in Greenbrier County, where her family has farmed for six generations. She taught abroad before moving to West Virginia, where she is a yoga instructor and has practiced massage therapy.

This is Turner’s first time running for public office, but she volunteered for the Bernie Sanders campaign in 2016. Turner said that she was inspired to run after watching a documentary on Netflix called “Knocking Down The House,” profiling four women running for the House in 2018 — including West Virginia’s Paula Jean Swearengin, this year’s Democratic nominee for Senate, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a freshman House Representative from New York.

“You know, I’m only one year older than AOC,” Turner said. “Just showing her victory and how she was able to do that with just a grassroots effort was extremely inspiring, for me.”

Turner is one of four women running for Congress in West Virginia through the movement West Virginia Can’t Wait. She’s also one of more than 40 members who advanced in the June primary.

All of the politicians in West Virginia Can’t Wait have pledged to reject corporate contributions. For the District 3 race, that means Miller has been able to outraise Turner by at least $550,000, according to data from the Federal Election Commission from January 1, 2019, through June 30, 2020.

On Renewable Energy And Economic Development

In Southern West Virginia, where the coal industry was once a major employer and still provides a hefty chunk of jobs, census data from 2010 note that the area holds low college graduation levels and a median household income that’s almost half the national average.

“You’ve got a lot of people who don’t have a highly diverse skill-set,” said MaryBeth Beller, an associate professor of political science at Marshall University. “We don’t have a terribly diverse economy in District 3, and people are hurting.”

The county’s largest coal miner’s union, the United Mine Workers of America, has declined to endorse either candidate for office.

The union has endorsed politicians from both parties this year, including Republican Sen. Shelley Moore Capito for Senate and Democrat Ben Salango for governor, but UMWA members across the southern counties, where West Virginia’s coal jobs are most abundant, will not throw their weight behind either House candidate for 2020.

Turner says that if elected, she would advance policies for a “just transition” — the idea that as the country transitions away from fossil fuels toward cleaner forms of energy, the federal government should ensure coal-dependent communities and workers’ livelihoods are secure, by investing in these opportunities and connecting them directly with jobs in the renewable energy sector.

“A politician can’t really come in and say ‘I’m gonna bring all the coal jobs back, and I’m going to change the direction of the economy,’” Turner said. “But, what we can do is make sure that we are looking at where communities have been hurt by this transition, and looking at [how we can] help communities by investing in our people.”

At the WVU Center for Energy and Sustainable Development, director Jamie Van Nostrand says the need for a just transition becomes more urgent as climate change in the Mountain State gets worse, and as the demand for nonrenewable energy across the country drops.

“We had some pretty serious flooding four years ago, which I think is pretty largely attributable to the impacts as the temperatures increase, as humidity increases,” Van Nostrand said. Miller referred to the same floods during a 2019 committee hearing on ways to enhance U.S. resilience to climate change.

“The climate crisis is urgent, and it needs to be addressed on a bipartisan basis,” Van Nostrand said. “The world doesn’t care whether you’re Democrat or Republican. Mother Nature doesn’t care, frankly.”

Miller is one of five Republican members in the Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, created in 2019. Theoretically, Van Nostrand said Miller’s minority position could lend a hand to the nuance of West Virginia’s situation and help find common ground solutions with legislators across the aisle.

Yet, Miller’s voting record suggests she opposes most Democrat-backed legislation to address climate change. Miller said in an email to West Virginia Public Broadcasting that she uses the position to “[hold] the line against many radical proposals that will accomplish nothing except kill jobs in West Virginia.”

Miller cited a bill in one email that she co-sponsored with Congressman David McKinley, to demonstrate her commitment to “promoting West Virginia energy.” The Energy Security Cooperation with Allied Partners in Europe (ESCAPE) Act would ensure that U.S. oil will be promoted to the country’s allies abroad, to reduce their reliance on Russian energy. The bill was introduced in late July and was referred to the Energy and Commerce committee.

To Van Nostrand, “you can’t really reconcile” the differences between what this ESCAPE Act offers, and broader actions by the mostly-Democrat House for renewable energy.

“Greenhouse gas is a global pollutant,” Van Nostrand said. “It doesn’t matter whether the natural gas is burned in the United States or exported and burned in Europe, it’s going to contribute to concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, which is going to contribute to climate change.”

Third District Race Results Could Boil Down To Voter Turnout

Political experts nationally expect the Third District race will be an easy win for Miller. At the University of Virginia, political scientist Larry Sabato of Crystal Ball predicts the Third District will remain safe for Miller, due to her own and the president’s incumbency advantages.

Beller from Marshall University adds that Turner won her primary election in June with a slim 67-vote lead over three other Democrats. This might negatively affect Democrat turnout.

“What typically happens is that a lot of people whose initial candidate doesn’t win tend to not want to participate as much in the general election,” Beller said. “It actually is going to come down truly to voter turnout and party loyalty as to whether or not this is a competitive race.”

Election Day is Nov. 3, with early in-person voting from Oct. 21 to Oct. 31. Registration forms and absentee ballots can be requested from each county’s clerk. The Secretary of State’s office lists each clerk’s contact information on its website.

Emily Allen is a Report for America corps member.