Two years ago, residents of Minden, West Virginia, asked the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to do more testing and consider the town’s soil and water to be a health and environmental risk in need of another cleanup.

Last September, residents received the news that, after analyzing new data, the agency proposed listing Minden on the Superfund National Priorities List (NPL). A final determination was supposed to happen this spring, but the partial government shutdown has pushed that back.

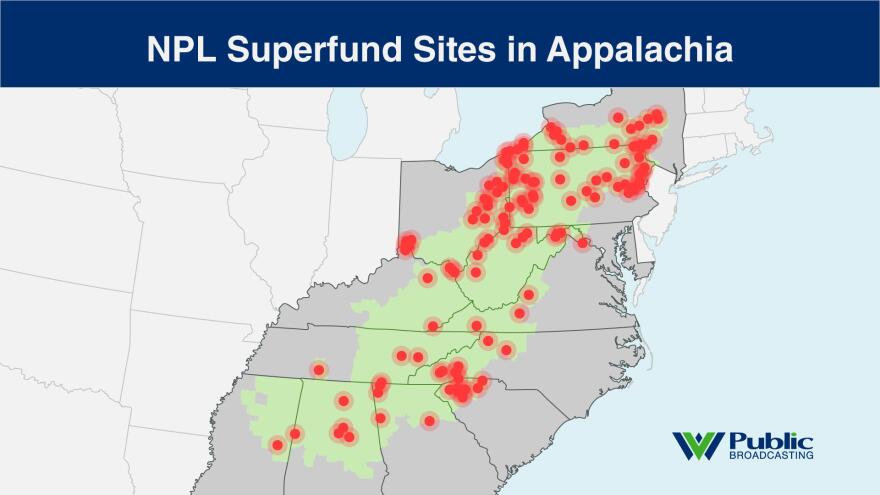

How is the delay affecting residents? The NPL is a list of the most toxic contaminated sites in the country. Qualifying for the NPL means the federal government will pay for another clean up.

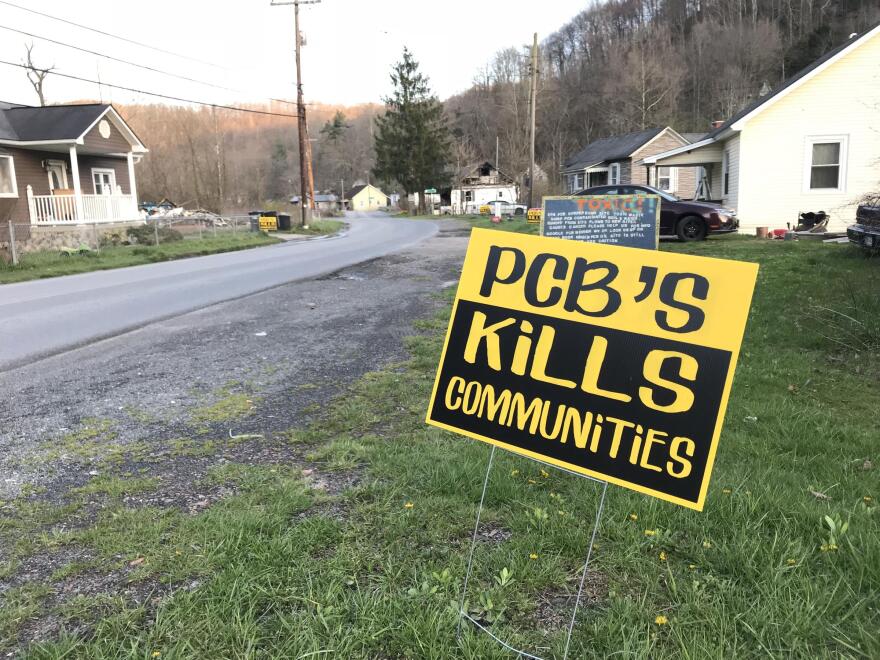

This week on Inside Appalachia, we are taking another look at a story that aired in the summer of 2018 about the history of how an entire town was contaminated with the harmful chemical polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and the government cleanup efforts to mitigate the problem. Residents were faced with the possibility that the contaminants caused cancer and made it impossible to sell their homes and leave.

In the 1980s, the EPA found that Shaffer Equipment was responsible for contaminating the town’s soil with PCBs. The company rebuilt electrical substations for the local coal mining industry.

The EPA inspected the site and found several hundred transformers and other electrical equipment filled with oil containing PCBs. The EPA found elevated levels of PCBs in the soil near the Shaffer site and along a drainage ditch of a local creek.

In 1984, the EPA declared a portion of land in Minden a Superfund site, meaning it had been contaminated by hazardous waste and was a candidate for cleanup. The agency spent millions of dollars to remove the PCB contamination from the soil in Minden. But local residents were concerned that the PCB contamination was still in the ground and asked the EPA to put their community of 250 people on the Superfund National Priorities List, the sites in greatest need of cleanup.

In the fall of 2018, the agency determined that placing Minden on the list was possible with a final ruling to come in the spring of 2019. That decision is likely delayed now, both from 20 years’ worth of budget cuts to the NPL program and the recent partial government shutdown.

For some there, like Susie Worley-Jenkins, the Superfund NPL designation isn’t enough. They want financial assistance to relocate. And they want the EPA to do even MORE in-depth testing. The latest rounds of soil sampling largely only went six inches deep. Advocates say the pollution likely goes deeper and the cleanup would need to as well.

There is also the concern that the PCB-laced water will continue to flow out of the area’s abandoned mines, whose cleanup falls on the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection.

One reason for their concern is residents believe cancer rates are connected to the tainted soil. West Virginia University cancer researcher Dr. Sarah Knox said proving these claims for a small community of 250 people like Minden would be time consuming, expensive, and difficult.

“Because there are different physiological processes involved in cancer and different factors that affect these things, you have to really do a strict methodological study over a period of time to try and differentiate the clusters from the non-clusters and to see if the clusters are just chance, which they can be,” she said.

Finding funding to study cancer in Minden is almost impossible – cancer research funds tend to go to bigger projects with broader impact on more people.

Listen on Soundcloud

Take a look back at the original story.

Inside Appalachia is produced by Roxy Todd. Eric Douglas is our associate producer. Jesse Wright is our executive producer. Our audio mixer is Patrick Stephens. Catherine Moore edited this episode. We’d love to hear from you. Tweet us @InAppalachia.